Legacy of Britain's Cold War nuclear bunkers and monitoring posts

If you gave them a second glance – and you probably would not – you might think they marked the site of a water storage tank.

But these places have never had anything to do with providing modern utilities. Indeed, they were there to monitor their destruction. For beneath lie underground bunkers, originally set up to measure the impact of a nuclear weapons strike on our country.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThey are not in use now and their original function might now seem rather unreal but the bunkers, or monitoring posts, were once part of detailed preparations for nuclear war.

This year marks 30 years since that war was judged unlikely to happen and remaining monitoring posts were shut down.

Across the UK around 1,500 posts were constructed, largely in the early 1960s, for the UK Warning and Monitoring Organisation. More than 100 were built here in Yorkshire. They were staffed by volunteers, members of the Royal Observer Corps. In the event of war, measuring the force of a nuclear burst, the direction of its centre and the amount of radioactive fall-out afterwards would have been a sobering job.

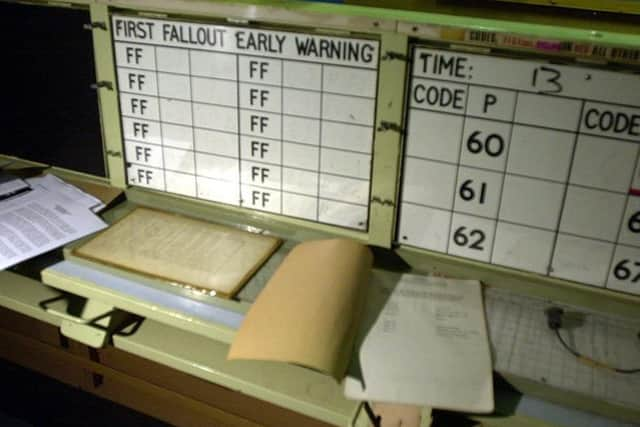

Yorkshire ROC monitoring posts would then have usually sent this information via a direct phone link to group headquarters at York, and from there it would have gone on to sector command at Lincoln, where it would have been used to draw up a picture of damage to help the authorities decide how best to organise civilian life.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe posts were not manned continuously but in periods of international tension, teams of three would be stationed at each one, waiting for the attack-warning speaker on the wall to relay the news everyone dreaded. And if it had done, the personnel would likely have needed to stay underground for several weeks.

Taras Young, author of the book Nuclear War in the UK, says governments took the threat of nuclear attack very seriously during the Cold War. “The network of ROC posts would have been extremely useful in pinpointing which areas had been hit. The information they would have gathered would have meant the number of survivors could have been calculated and assistance sent to the right areas.”

Few people not involved in this process would have known anything about it. ROC members signed the official secrets act and could not talk openly about their work, as they were part of a clandestine world that might have seemed rather terrifying to those outside it.

The origins of the ROC go back to 1925 and during the Second World War, the corps performed a vital role in identifying and tracking enemy aircraft. In the mid-1950s, with Cold War tensions rising, it took on the additional task of monitoring the impact of possible nuclear attack. Posts were rebuilt underground, well protected to resist bomb blasts.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBy the mid-1960s, radar technology had improved to the extent that the ROC was largely no longer needed for aircraft monitoring and posts focused entirely on the nuclear threat. This continued until 1991 when posts were shut down and the ROC volunteers largely laid off.

Since then monitoring posts have passed back into the hands of private landowners. Some have been demolished or filled in, while a few are being preserved by enthusiasts but most have just been left to drift quietly into history. They are, as you might expect, generally impregnable and inaccessible.

In the bunkers a vertical shaft led down into a small subterranean room encased in reinforced concrete. In it, furniture was limited to a table, chairs, some bunk beds and a cupboard with provisions. A separate area housed a chemical toilet. Electricity came from a heavy-duty battery, periodically charged by a portable petrol-driven generator. Drinking water was stored in Jerry cans. Food was in the form of service ration packs.

Each monitoring post had three main pieces of equipment. The Bomb Power Indicator registered the pressure wave from a nuclear blast passing over an instrument on the surface, while the Ground Zero Indicator photographed the fireball of an explosion and recorded its direction. The Radiation Meter recorded subsequent fall-out levels.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt would have been cramped, chilly and damp in a bunker, although there was a pump should standing water have accumulated. Taras Young says: “The bunkers were manned by extremely dedicated people who felt they were working for a greater good, even being prepared to leave their families during a crisis to serve their country.”

One of them was Barrie Hodkinson, who for decades ran an electrical shop in Grassington and was a prominent figure in the local community. He served for around 30 years in the Royal Observer Corps and was part of the group of Upper Wharfedale locals who manned the posts at Grassington and Buckden.

Sadly Barrie is no longer with us but in an interview in 2013, he talked about his feelings at possibly having to perform the rather macabre duties of monitoring destruction around him. “I was of the opinion that because both sides had the bomb, war was something that would never happen,” he said, “but I was prepared to stop down in the bunker.

“If bombs came, whoever was down there would have stayed there. What could you feel? We were just a cog in a wheel. What would have happened if you were stuck there? It wouldn’t have been a nice thing but if something had happened I’d rather have been doing something than not. At least you’d have known what was going on.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne person more familiar than most with bunkers in Yorkshire is Nick Catford. Remarkably, he has visited every single one in the country.

“Once the Cold War was over, it was clear these places needed recording for the purposes of history. I took on the job of surveying them all – it took seven years.”

Since 1984 he has been a member of an organisation called Subterranea Britannica, open to all people with a fascination with man-made underground structures.

Nuclear bunkers form a significant area of interest for its members and especially for Nick, who has written a book entitled Cold War Bunkers.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I have always found secrecy interesting,” he says. He has even acquired his own bunker which he is currently restoring.

It is easy to understand curiosity over what is largely hidden from view. Remaining ROC monitoring posts will also be of interest as important artefacts of a period of history that, to many, will seem a world away.

And yet today they stand as chilling monuments to a war that never came.

Monuments not for exploring

In Yorkshire ROC monitoring posts were built at over 100 locations, from Stockbridge in the south to Reeth in the northern Dales and from Kilnsea on the east coast to Todmorden in the Pennines.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdToday, remaining bunkers are on private land and are not open to the public. They have long since been stripped of any furniture and equipment.

They are also generally locked because of their condition and no-one should attempt to enter them without the permission of the owner.

The ROC group headquarters at Acomb in York, on the other hand, has been developed into a museum by English Heritage.

Visit www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/york-cold-war-bunker for details.

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.