Ellerby Hoard: The incredible story of the once in a generation historic find beneath a Yorkshire kitchen floor

In 2019, a couple were renovating their 18th-century property in the village of Ellerby, near Hull, when they made the discovery of a lifetime beneath the kitchen floor.

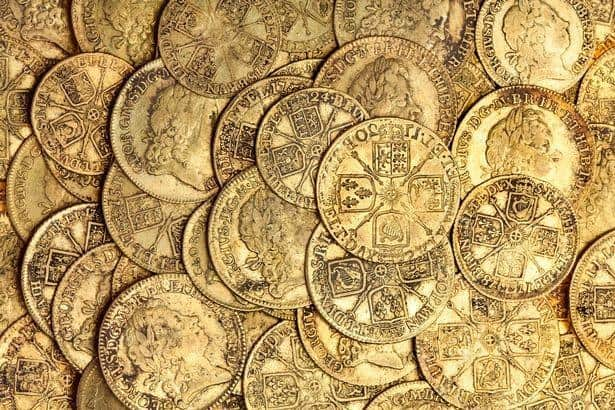

Buried inside a small cup were over 260 gold coins from the 17th and 18th centuries, dating from the reigns of King James I through to King George I. They are to be auctioned in London next month and could fetch over £250,000 for their anonymous finders.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe discovery presented numerous questions which baffled historians – namely, why was the Hoard ever hidden at all? It is believed to have belonged to Sarah Fernley, nee Maister, the sister of a leading Hull merchant, William Maister, whose business operated out of the Old Town. She married into the Fernleys, another of the city’s trading families, and is known to have lived in Ellerby after she was widowed and until her death in 1745.

In 1700, her husband Joseph’s family had purchased the manor house of Wood Hall, and in 1820 a new house named Wood Hall was built, this time by the Maisters. Both families owned numerous properties in the village.

Experts were puzzled because by Sarah’s lifetime, the Bank of England had been established, paper currency was in circulation and wealthy families like the Maisters and Fernleys would have been using both and keeping their money in secure bank vaults – not stashed away at home.

The National Trust now owns Maister House in the Old Town, the grand residence and business quarters built in 1745 by Sarah’s nephews Henry and Nathaniel, the sons of William who took over the company, which traded with the Baltic ports.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA curator who has studied the family papers said: “In 1739 there was a reissuing of coinage and according to at least one surviving letter between Henry and his younger brother, Nathaniel, apparently the family were concerned about rumours of forgeries. Did Aunt Sarah get worried and stash some older coins in case?

“Alternatively, it is possible Sarah was concerned about war with France (given Ellerby’s proximity to the coast) and possible invasion in the 1740s (including French support for the Jacobite uprising in August 1745) and hid some coins late in her life without telling anyone.”

The Maisters’ fortunes had declined by 1840 and Maister House, which Henry’s son Henry had inherited before dying childless, was let by 1880. The family archives are held by Hull History Centre.

Coin expert Gregory Edmund from London auctioneers Spink & Son clearly remembers the day he overheard the first phone call about the Ellerby Hoard.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn July 2019, the couple contacted his office to share details of a number of ‘gold, shiny and yellow coins that came from the earth’.

"We get a lot of calls from people who’ve found Granny’s stash in a biscuit tin in the attic and think it’s gold, but is actually old brass. I remember the call vividly.”

Alarm bells rang for Mr Edmund when they told him one of the pieces bore a misspelling of King Charles II’s Latin name – and just days later all three were meeting in a cloak-and-dagger rendezvous at a hotel near York Station.

"They had these canvas bags and were just counting the coins out – when I saw 35 gold coins from the reign of Charles II I realised this was quite special.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"They were spilling out of this tiny cup that was smaller than a can of Coke. They were so many handmade coins from pre-1660, along with machine-made ones as the former were phased out in the 1690s, all mixed in together, which is very unusual. There was a Portuguese Brazilian coin (which was accepted tender in England at the time) – the whole hoard was beyond special, unique and a moment when I pinched myself.”

The coins were not legally declared treasure because they did not all meet the threshold of being at least 300 years old, meaning the finders – who had lived in the house for 10 years – were able to keep and sell them, though the British Museum has taken the Brazilian coin for public display.

"The legal test is that the hoard is equated with the date of burial – so they were only 292 years old, though some of the coins pre-dated 1719. This situation had never come up in an archaeological sense before.”

The coins themselves were described by Mr Edmund as ‘workhorses’ far from mint condition which had been heavily used. The cup from the reign of Queen Anne – even older than the coins – is to be kept by the couple.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"We spoke to a pottery specialist who identified a Queen Anne excise mark, meaning it came from a commercial setting – likely a pub or tavern. It’s a bit like taking a pint glass home with you! It was made from stone and now has a backstory of its own, as Sarah and Joseph were clearly careful with their kitchen pottery if it had survived 15 years by the time it was buried.

"The whole hoard is only worth around an eighth of one of the Maisters’ Baltic timber shipments at the time. It raises the possibility that there is more buried somewhere in other houses they owned still to be found.

"Sarah’s Maister brothers were MPs for Hull so she would have had her finger on the pulse with investments, politics and been well connected. The prevalence of the very old early coins suggests a miserly streak and clear distrust of banking. When they were buried, there was no economic crisis in Yorkshire, the Jacobite rebellions were still 20 years away, so it could just have been a saving and spending purse for her. Perhaps when she became infirm she forgot to tell her family about it.”

When Sarah died, having outlived her children, the estates passed back to her Maister nephews and the Fernleys had no claim to them.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"The interest in these coins had gone beyond the usual collecting base and they’ve become a viral news story. I am confident they can exceed the £250,000 estimate. Individually they are only worth about £200 each, their intrinsic gold value, but this is because they had hard lives – some of them would have been declared counterfeit at the time. The cache is a fascinating snapshot of the period.”