Fall of the Berlin Wall and the story behind it 30 years on

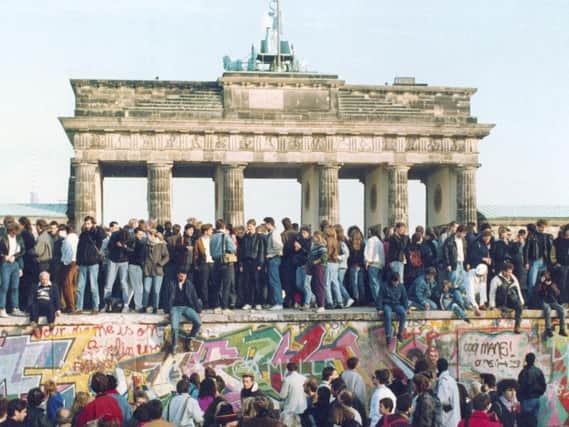

It was November 9, 1989 and the Berlin Wall, which had controversially divided the city for 28 years, was being demolished.

It’s difficult to comprehend the emotion felt by the half a million people who gathered in mass protest in East Berlin that day as the wall, dividing communist East Germany from West Germany, crumbled.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere was cheering and crying as this hated barrier was slowly dismantled and thousands of East Germans flooded through the now unmanned checkpoints to reunite with long-lost relatives and friends – the first time they had been free to travel since 1961.

In the end, the wall’s demise was as sudden as it was unexpected. Following months of mass protest, a poorly briefed official announced – erroneously, as it turned out – that visa restrictions would be immediately eased, prompting furious crowds to demand that the gates be opened.

Remembrance Day art installations made up of 50,000 poppies go on show in YorkshireWith no word from their superiors and fearing for their safety, the border guards obliged. It ended the division of Berlin, Germany, and marked the beginning of the end of the Cold War.

The wall’s origins date back to the end of the Second World War, when Europe was carved up by the Soviet Union and its former Western allies, and the Soviets created what Winston Churchill called an “Iron Curtain” splitting the East from the West.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGermany had been divided up by the occupying powers – the US, UK, France and the USSR. East Germany became the Soviet Union’s foothold in Western Europe and Berlin was split four ways, with West Berlin becoming an island surrounded by communist East Germany.

The wall was eventually built in 1961 because East Berlin was haemorrhaging people to the West. Around 3.5 million East Germans fled the country between the division of Germany at the end of the war, and the rise of the wall – roughly 20 per cent of the population.

It became symptomatic of communism’s iron will, but it was also its worst advertisement – a supposedly defensive rampart built not to keep people out, but to keep them in.

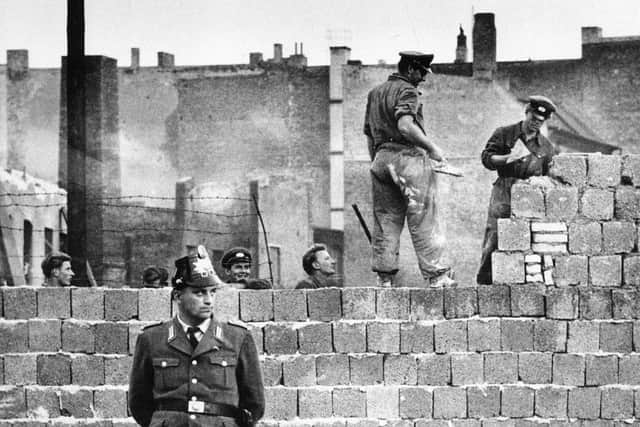

Just a few weeks later, on the morning of August 13, residents awoke to find that barbed wire had been rolled out across the border overnight, and that roadblocks had taken over main thoroughfares.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad'The lads have been through hell' - Yorkshire soldier's words from front line shared in book capturing horrors of First World War trenchesBuilt narrowly within East German territory to avoid encroaching on allied land, the wall ringed West Berlin completely, at a length of 156 kilometres.

It was constructed with staggering speed and included two physical barriers sandwiching a so-called “death strip”, a gravel-covered no man’s land that provided clear lines of sight and fire should anyone attempt the crossing. At different points the defences included attack dogs, ground spikes, anti-vehicle trenches, and bunkers filled with border guards.

Berliners were left stunned. Families were divided, livelihoods wrecked, visitors trapped, and central Berlin again ruptured by watchtowers and weaponry.

Willy Brandt, then mayor of West Berlin, compared the wall to a concentration camp, and issued an impassioned plea to East German authorities “not to shoot your fellow countrymen”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor Gunter Litfin, a 24-year-old tailor and East Berlin resident, the wall was particularly troubling. He had just taken on an apartment near his workplace in the West, and had been there decorating only the day before.

With all land routes to his new home blocked, he elected to swim for it, hoping to elude detection in the murky waters of the River Spree. He made it all the way to the opposite bank before he was shot in the back by East German police. Litfin was buried in East Berlin under the watchful gaze of the Stasi, the victim of a “tragic accident”.

It’s estimated that around 250 more people died while attempting to reach West Berlin. The last of them, Winfried Freudenberg, fell to his death from a home-made hot air balloon, just a month before the wall was reduced to rubble.

He had no way of knowing that the border would suddenly open – it caught people and government equally by surprise. In the same year Erich Honecker, East Germany’s hard-line leader, told journalists that “the wall will be standing in 50, even 100 years”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn the end it didn’t last 30, but three decades on how significant was the wall’s collapse? “It ended in an unexpected way. It didn’t end due to governments or systems but through the action of people,” says Simon Ball, Professor of International History and Politics at the University of Leeds.

The fascinating story of the Yorkshire landmarks that were camouflaged during World War TwoWhat makes it all the more remarkable was it happened before the galvanisng era of the internet and social media.

At the time, though, there were very real fears of a crackdown from the East German authorities, with memories of the Hungarian Revolution in 1956, the Prague Spring of 1968 and the Polish crisis of the early 80s, still fresh in people’s minds.

The fact that there wasn’t a backlash from the Soviet regime was a sign of its growing impotency. “The Soviet Union was collapsing and the leadership of the Soviet communist party understood that it could no longer control what it had unleashed,” says Prof Ball.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt’s perhaps easy to overstate the importance of the wall and its collapse. “It mattered to Europe and it mattered to the structure of world politics, but it mattered most to Germany and the bordering states... It’s like an earthquake, the nearer you are to it the more important it is.”

In Europe, it showed that communism and the system of party control, didn’t work. But you only have to look at China’s unstoppable rise over the past three decades to realise that the demise of communism, to borrow Mark Twain’s phrase, has been greatly exaggerated. “It wasn’t the end of history,” says Prof Ball.

The euphoria that greeted events 30 years ago has long since evaporated and we have learned (though President Trump may disagree) that building a wall is not a long term answer to systemic problems.

What we can say is that the collapse of the Berlin Wall was undoubtedly a victory for people power. “It showed that unexpected events do make a difference in international politics and also that individual decisions by individual people can make a difference,” says Prof Ball.

“Those involved in the protests in October and November 1989 were not told to do so, each person acted for their own motives and there was enough of them unified in the moment to make a difference.”