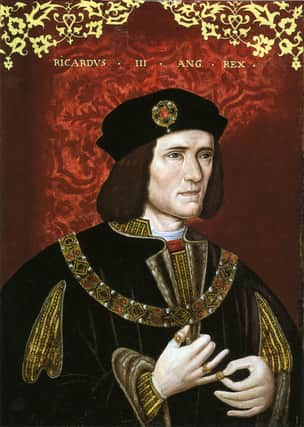

Richard III and the Princes in the Tower: Why Yorkshire academic believes he has solved the centuries-old mystery

Public fascination with Richard III and his short but bloody reign as king has rarely abated since his death in battle in 1485 brought about an end to the Wars of the Roses and ushered in the Tudor era.

From Shakespeare’s famous play to the discovery of his remains under a Leicester car park in 2012, there has long been worldwide interest in his story – and now a Yorkshire historian has put Richard back into the headlines after uncovering new evidence relating to one of the most contentious chapters of his reign, the disappearance of his nephews, the so-called Princes in the Tower.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdProfessor Tim Thornton, from the University of Huddersfield, has published new research for History, the Journal of the Historical Association, which he says backs up the idea that Richard was responsible for the murder of his young relatives King Edward V and his brother, Richard, Duke of York in a dispute about succession to the throne.

“In some ways it is the greatest mystery in British history – to have a king disappear in the way Edward V did,” says Prof Thornton as he speaks to The Yorkshire Post over Zoom.

The princes were aged just 12 and nine when Richard took the throne in June 1483 following the death of his brother King Edward IV. The two boys were Edward’s only sons but before the eldest, Edward, was due to be crowned king, the pair were declared illegitimate and Richard III seized the throne.

There were no recorded sightings of them after summer 1483 and it has long been believed by many that they were killed on Richard’s orders – although his defenders point to a lack of hard evidence to connect him to their disappearance, with other candidates suggested as potential murderers. They included Henry VII, who became king in 1485 after Richard was killed at the Battle of Bosworth.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAround 30 years later in the early years of Henry VIII’s reign, the celebrated but controversial statesman and author Sir Thomas More quietly began researching and writing a History of King Richard III; a piece of work that would not end up being published until well after More’s own death in 1535.

More named two men, Miles Forest and John Dighton, as the murderers of the princes. More claimed that they were recruited by Sir James Tyrell, a servant of Richard III at his orders.

Until now, many people have questioned this story as being written long after the event, as “Tudor propaganda” to blacken the name of a dead king, and even suggested that the names of the alleged murderers were made up by More.

However, Prof Thornton’s research has unearthed new evidence to substantiate More’s allegations. Two of More’s fellow courtiers were the sons of Miles Forest, one the men named by More as having killed the princes.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdProf Thornton says the new knowledge that the sons of the chief alleged murderer were living and working alongside Sir Thomas More make his account much more credible.

“I’m very confident it is an accurate account of the events,” he says. “The alternatives now seem to me to be very, very unlikely.”

The article explains: “During the whole of the period from 1513 to 1519, and beyond, when More was at work on Richard III, he was in touch with the sons of one of the men whom he said killed the princes. Further, More spent a significant proportion of that time on embassy in the Low Countries and in particular in Calais, thereby bringing him into the location where he was writing that the other – surviving – murderer, John Dighton, may well have been living.

“It should be recalled that More described his sources for what happened to the princes not directly as the confessions obtained when Tyrell and Dighton were brought to the Tower in 1502, but what he had ‘learned of them that much knew and litle cause had to lye’. What better way to describe the witness of the sons of Miles Forest, and perhaps of Dighton himself?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“This evidence opens up the strong possibility that Edward and Miles junior [Forest’s sons] were the channel for information about the murders, passed either direct to them from their father Miles Forest, or at just one remove via their mother Joan, or that they represented a very immediate connection to others who had been associated with their father at the time of his activity in the Tower.”

Prof Thornton explains that he worked out the connection by tracing the movements of the Forest brothers in the 1510s and 1520s – and realising for the first time that they had had direct contact with More.

“More has identified some sources that were very close to the events of 1483 – the sons of the man he considers as a chief murderer of the Princes in the Tower.

“This is what I think no one has previously appreciated. When I realised the connection, that was an extraordinary moment.

“Why nobody had spotted that before, I have no idea.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdProf Thornton admits it is unclear why Forest’s sons would have confirmed to More their father was among the killers but he adds there is other evidence that support the case for him being involved in the murders. He says this includes the annuity granted to Forest’s widow by the king following his death in 1484.

Prof Thornton says he went into his research with an open mind about More’s allegations and other histories of the events surrounding the princes written around the same period.

“I was aware of the cynicism that has been expressed about Thomas More’s account. More was not only writing a factual narrative, he was trying to describe tyranny.

“But I think what some people have done too much is emphasise that element of it. He was part of an effort to create for the first time a detailed narrative about what actually happened in 1483. The challenge that people at the time in the 1510s faced was that they were writing a history of a period that was still very fresh – many of the people had been alive in 1483 and had been participants in this period of this civil war. Some had played considerable roles in the coup which Richard had led.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It is contemporary history More is writing of a very pressing kind and it is about things that are highly controversial.

“More was an extraordinary man, a brilliant man. In the history, he is writing a brilliant account of tyranny. But he is also trying to write an account of what happened in 1483 in a world where there were very few accounts of what had happened. You couldn’t go and read a straightforward account of what had happened in those years.

“The history wasn’t published in More’s lifetime but people like him were starting to construct a narrative.”

One of the question marks that has been raised about the veracity of More’s account in the past has been the time he spent in his childhood in the household of John Morton, a key foe of Richard III’s.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut Prof Thornton says the high-stakes politics of the time meant that it was almost impossible to find any truly neutral party on the matter of Richard and such a connection should not be a reason to dismiss More’s account.

“One of the fundamental points I’m trying to make is this was like trying to write the history of the English Reformation during Queen Elizabeth’s reign when everybody has changed sides between Catholic and Protestant or in the recent past people in continental Europe trying to write the history of the Second World War. It is a very complex experience and it was the same thing for people like More to think about when doing a history of a civil war in their own country.”

He says the “sensitivity” of what More discovered may have been why the material was never published in his lifetime.

Prof Thornton says it is very professionally satisfying to be working on research about a period of history that continues to attract so much public interest.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It engages people for different reasons. There is a perception that this is the bridge between the medieval and modern period. For some people, Richard represents the North and even Yorkshire. There is a sense of extraordinary change which takes place in England. It does have a grip on our imagination. It is not surprising this extraordinary mystery does still attract attention.”

New BBC series to examine riddle

Professor Tim Thornton will contribute to a new BBC Two series examining the disappearance of the princes, due to be aired later this year.

He will be among those involved in the four-part series Unsolved Histories with Lucy Worsley, with one of the episodes focusing on the Princes in the Tower story.

Worsley says: “I’m thrilled to be revisiting some of the big-hitting stories from history that just keep sucking us in, and like everyone who works at the Tower of London, I just can’t wait to share the next twist in the tale of what we think we know about the ‘murder’ of the Bloody Tower’s ‘Little Princes’. But I also really love the fact that this isn’t just a series about the past. It’s also about what the past means today.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSupport The Yorkshire Post and become a subscriber today. Your subscription will help us to continue to bring quality news to the people of Yorkshire. In return, you’ll see fewer ads on site, get free access to our app and receive exclusive members-only offers. Click here to subscribe.

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.