Scientists in Bradford to uncover the secrets of mummies

Now with the first ultra-high definition CT scanner of its kind, scientists in Bradford can examine ancient treasures - and Egyptian mummies - in more detail than ever before.

Housed at the University of Bradford's School of Archaeological and Forensic Sciences, this advance in scientific equipment opens the door to amazing new discoveries.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTo project lead and chair of the department, Prof Andrew Wilson, the possibilities are far reaching.

Not just with the imaging archaeological artefacts, he stressed, but with ancient mummies that may be too delicate to otherwise examine.

The machine is called a 50 FujiFilm NewTom 7G Plus Cone Beam CT - and there are only around 50 in the whole world. This is the first in the UK, and the first outside healthcare.

Scanning the most fragile of human remains and even the most delicate of artefacts, it can share what’s hidden inside without inflicting any damage.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

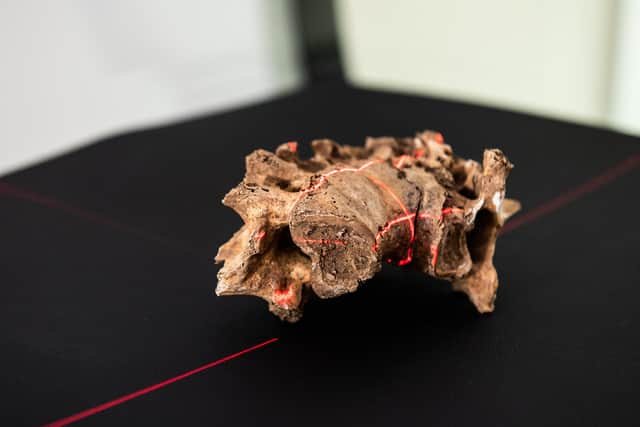

Hide AdSo far scientists have investigated a fused archaeological vertebrae - as well as a sealed 19th century box uncovered from a local dig.

Inside were a pair of glasses inside, complete with pristine glass lenses and tortoiseshell frames.

Department head Dr Cathy Batt: “The glasses were in a box inside protective packaging but we can’t look directly inside the box because it’s so fragile.

“What this unit does is allow us to look at archaeological and forensic materials in a lot more detail.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“For example, we can study cremation urns where ash and soil is often mixed with human remains and we will be able to determine the different materials, and whether pyre goods were incorporated.”

It’s not unusual for archaeologists to use such technologies, but more usually they are reliant on healthcare scanners outside of clinic hours when they aren't needed for patients.

Now, its use is possible thanks to a share of £3m funding from CapCo, the Capability for Collections fund, part of the Arts and Humanities Research Council’s (AHRC) allocation.

Robert Janaway, associate professor, explained that using healthcare scanners wasn't ideal - notwithstanding the pressures on the NHS, radiation strengths used in this field were much lower.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Having our own unit means that we can modify the radiation exposure to see evidence more clearly," he said.

And while the scanner will mean students can learn using the very latest technology, it will also open up research opportunities and links with other settings.

“There will be uses for this that we haven’t yet thought of and as a non-destructive testing method it will almost certainly lead us to groundbreaking discoveries," said Dr Batt.