The Baedeker air raids and the destruction they caused to historic York

It is claimed that York is a place where, if a paving stone must be replaced, work has to be stopped, and archaeologists called in – because it is almost inevitable that something of historical significance will have been discovered.

But next week there will be the unveiling of a fascinating new interactive website, three years in the making, which reveals a completely different “take” on one particular event that changed the city forever. And for once, it concentrates not so much on what is beneath our feet, but what came from the skies.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt commemorates the early hours of April 29, 1942, when Hitler’s Luftwaffe dropped many tons of bombs on the civilian population of York, leaving 79 dead. Gone too was the historic Guildhall, with the landmark railway station severely damaged.

Five of the victims were nuns, sheltering in one of the wings of the Bar Convent, which was flattened by a direct hit. One of the sisters had been ill, in the sick bay, and, when the sirens sounded, had told her nursing colleagues to take shelter. They replied that their place was with her. They all died together.

York has welcomed pilgrims and sightseers for many, many hundreds of years. They’ve come to pray at the great Minster, and to venerate relics both there and in other historic and holy churches. They’ve come for cultural events and the races, and they’ve come to wander the Shambles, to walk the walls, and to enjoy some first-class hospitality in bars, pubs and restaurants. And a handful have come for quite a different purpose – to spy.

After the dust and chaos of the First World War had settled, and “normality” had returned, many of Britain’s towns and cities were the focus of visitors who arrived from all over Europe.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThey, and how they got here, were the start of the tourism industry. But a significant few had an ulterior motive. As communism took over in the east, and the Nazi stranglehold on Germany and its neighbours grew, there were travellers among them who were far from innocent.

Their jaunts had a sinister ulterior motive – they needed to discover where air defences might be located, how prepared (or not) we were for war, where transport links had strengths or weaknesses.

Those who were spies all had one thing in common, a Baedeker Guide. Fans of Michael Portillo’s many railway journey series will know that he clutches an early copy of the guide as he rattles along from location to location. It is an incredibly detailed account of what to expect and where to go. a venerable version of today’s Lonely Planet or Rough Guides.

Dr Duncan Marks, York’s Civic Society manager and one of the team which has built and meticulously researched the website that chronicles the main night of terror when the Baedeker raids pounded York, observes: “It has to be pointed out that the British travellers of the thirties were not entirely innocent either. We also had a few who were, ostensibly, tourists, but who were also clicking away at installations that would be useful to the RAF.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The catalyst for the Baedeker raids on the UK was the devastating British attack on the northern German city of Lübeck in March 1942. Hitler snapped, and ordered that if one of the most beautiful cities in Europe was going to be damaged almost beyond belief, then it was going to be tit for tat.

"Bombing Britain would be not only to damage or destroy strategic centres of defence, but also to strike at the morale of the civilian population. The cultural significance of the raids cannot be understated”.

Marks, who lives in Harrogate, adds: “But please don’t think for a second that this was the only raid on York and its environs – there were 12 in all, each as frightening as the last”.

But those Baedeker Guides weren’t the only way that the Luftwaffe got its vital information – incredibly, only two years before the war began in 1939, there was an International Air Meeting at York Aerodrome, in Clifton, with 100 planes performing over the weekend of June 5 and 6. And of those 100, there were 23 foreign competitors, a full dozen of them German.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMarks adds: “What is even more astonishing is that, in the International Handicap Air Race, which was the highlight of the weekend, there were 18 competitors, and the German fliers came first, second, and fourth! Didn’t anyone from the RAF or the Air Ministry see how advanced and prepared that they were?

"And it wasn’t as if they were confined to the air space over Clifton – they were obviously allowed to buzz around pretty much as they liked because one of the pilots had a narrow escape when he ran out of fuel near Poppleton, and had to make a forced landing in a cornfield. His name was given as Herr Berlin. You really couldn’t make this up.

“There can be little doubt that these officers, who were in full Luftwaffe uniform, were also feeding back as much information as they possibly could, and they were welcomed with open arms – they even enjoyed a civic luncheon at the Mansion House, hosted by the then Lord Mayor, Alderman Thomas Morris.”

The information that reached Hermann Goering, the Reich Minister of Aviation, was put to good use, for detailed maps of where the German bombs landed show that they were precision sharp in hitting their targets, particularly in and around the station and the marshalling yards next to it. One plane dropped a straight line of bombs one after the other that showed particular skill – and knowledge.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

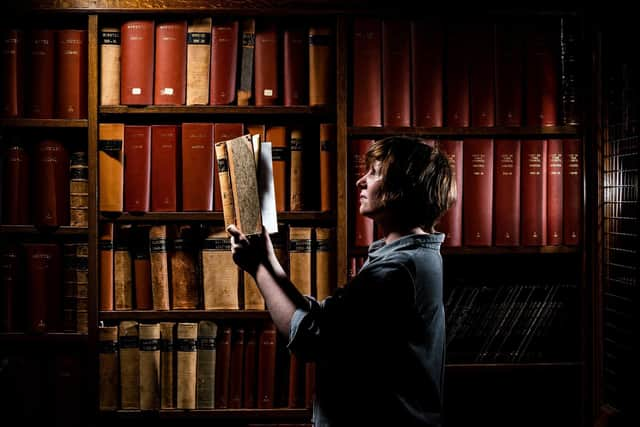

Hide AdMarks adds: “The most exciting thing for us has been the amazing amount of material that people have unearthed for the new website – family documents which have been kept in files for decades, for example, but which have come to light as relatives have died.

"They are all invaluable to anyone who wishes to research the era, and the events that ‘ordinary people’ lived through. A favourite of mine is the wonderful photograph of Ted and Mabel Stott, who were the postmaster and postmistress of Acaster Malbis, and to add to those highly responsible jobs, during the war years they were also volunteer air raid wardens – which meant that they must have been working loyally pretty much around the clock!”

And there were also a few surprises for residents of York today. When Rachel and Ash Jeoffrey put in a bid for their home in Acomb’s Carr Lane, they knew that they had what Rachel describes as “ a bit of a jungle” to the rear.

She recalls: “Just before we moved in, the then owner said that he had a surprise for us, and, when he had cleared back a few branches and undergrowth, he revealed a complete WWII air raid shelter underneath it all. We were even able to go down and sit in it, it was so well constructed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"It was clearly constructed for about four people, from blocks that had been made by hand, but I don’t think that I’d have liked to have been down there for any length of time – it was rather damp, and a bit scary. If bombs were falling, I’d had rather taken my chances crouching under the stairs.”

Rachel and Ash now have planning permission to build their own garden gym over the shelter. Their house was constructed in 1928, and they believe that the shelter was dug out ten years later – probably just as the Luftwaffe was showing off its skills at the Clifton aerodrome. But, for any archaeologists of the future, what lies beneath the new gym will be potentially there for investigation.

“It’s the best part of my job”, says Dr Marks, “bringing history to life. Because history is about real people, who left their mark on our society, and our landscape.”

For more information, visit raidsoveryork.co.uk