The Leeds lecturer hoping to be the next Sponge Bob

When you meet Ben Simpson, you might not be too surprised to find out what he does for a living. He wears a jacket that is covered in cartoons (he also used to be a fashion designer) together with a brightly coloured baseball cap, worn back to front of course. He also drives a vintage Rolls Royce car after trading in an old ambulance that he converted.

Doctor Simpo as he prefers to be known, is something of an eccentric. He is an animator, cartoonist and a senior lecturer at the Leeds Arts University where he is senior lecturer for the BA (Hons) Animation course and also the subject specialist for the newly formed Graphic Novel MA – that’s comic strips to you and me.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe says his interest in comics started at a young age growing up as an only child to a single mother in Holmfirth. “My mum went to work at a school and so I was pretty much brought up by my grandma,” he recalls. “Looking back, I think nowadays I would probably have been diagnosed with dyslexia but it wasn’t really a thing in the ’80s. I used to make up my own stories but struggled with sitting down and reading huge amounts of text. We couldn’t really afford expensive picture books, but I loved comic books, especially The Beano and The Dandy, and they only cost about 20 pence so I was allowed one every couple of weeks. I really enjoyed the words and pictures together in sequence.”

He now regards himself as “sequential narrative specialist” and his studio in a converted mill in Huddersfield is full of his works of art and ideas. You might, therefore, be surprised to learn that Simpson wasn’t very artistic at school.

“I didn’t even take art at GCSE,” he says. “I took music instead. I didn’t really start drawing until I went to college to do A-levels. I had a really inspirational art tutor who encouraged me and changed my expectations of what I wanted to be. I’d thought I might be a barrister until then. He opened up this whole world of art to me. As a child and even a young teenager, it never occurred to me that cartoons or animation could be a career.”

But it wasn’t until he embarked on an art foundation course at the then Leeds College of Art – now Leeds Art University – that he really started to explore the world of animation.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“There was a multimedia area tucked away in the basement of the college and they had what’s called a lunch box system, which has a television with a tape deck with a button on it that allows you to capture frames. I’d go down there all the time and taught myself to animate.”

Simpson started by making models out of plasticine and moving them around and then started drawing his own cartoons and animating them. “I didn’t really know what to do with it,” he admits “I was using biros, which is a mistake as the ink disappears over time, but I just loved it.”

After his foundation course, he went to the Glasgow School of Art to study Visual Communication following advice from his tutors.

“The only reason I went there was because they had a lunch box system but it broke after two weeks and they said they weren’t going to replace it. I then realised that the course wasn’t for me. There weren’t any animation courses at the time so I swapped onto the Environmental Art course which gave me far greater freedom to explore what I wanted to do. It was more of a conceptual art course. They gave us studio space and time to think and plan for ourselves what we wanted to do.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDuring this time he made his first comic book, which was a collaboration with other art students. They sold The Comic Book as it was called, around record shops in Glasgow and made enough money to produce a second issue, but Simpson soon realised that producing it took him away for his first love – being creative.

He was inspired and mentored by some top illustrators and artists during his time Glasgow’s Hope Street Studios in the early noughties, including the likes of Dave Alexander, Graham P Manley, Frank Quitely, Grant Morrison and Jamie Grant.

The support of people over the years instilled in him a passion for passing on his knowledge to others. It started during his degree when he taught in schools as part of an art in education programme.

“I did workshops with the children. I got them to come up with ideas for making plasticine monsters, then making them, and then I put them on display – we got around 400 which was amazing. I never had any one to inspire me in the world of animation when I was at school and I wanted these children to see that there are opportunities out there that school doesn’t necessarily tell you about.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNow Simpson is back in Yorkshire, he is holding workshops with children in Sheffield. He has two Reading Pictures, Seeing Stories workshops for eight to 12-year-olds lined up on April 11, at Ecclesall Library from 10am-12.30pm and then at Woodseats from 1-2.30pm.

Some of his insight is included in his recently published book – Bring Stuff to Life? which is available from university libraries. “I must have run a thousand workshops in schools and in the community over the years. I just want to teach young people that they can realise their dreams.”

He is also involved in the Anansi Project in Chapeltown, Leeds, working with the community using multimedia techniques to animate traditional African Anansi stories.

Simpson’s fondness for passing on his extensive knowledge comes from the enthusiasm bestowed on him from those that he was mentored by whilst attending the Glasgow School of Art and then the Pratt Institute in New York, where he spent six months on exchange learning everything about animation from the best in the business. “I feel very lucky to have been able to do that,” he says.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe then managed to get a place at the Royal College of Art in London to study an MA in Animation. “Once again I felt so lucky. There were 14 places and hundreds of people applied.” There he worked with the likes of Quentin Blake and Bob Godfrey, the man behind Rhubarb and Custard.

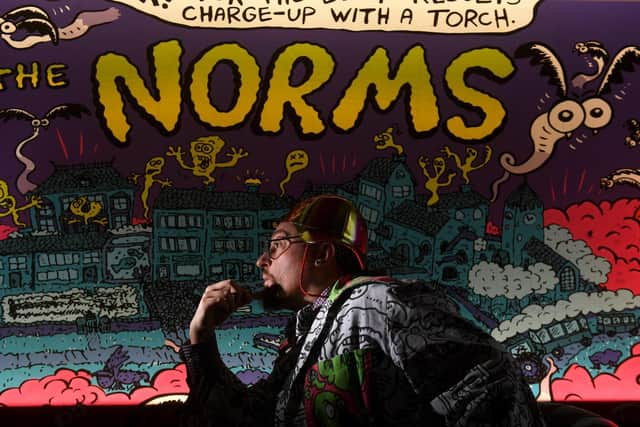

His animations, comic books and illustration- based works have been exhibited, published and premiered on a global scale. His cartoon films have been played at the New York Children’s Film Festival, Time Out Film Festival, London Independent Film Festival and the Holmfirth Film Festival in his home town. Following on from his highly acclaimed interactive and multi-visceral exhibition in 2018, The Norms: Process and Production – where he brought his first glow-in-the-dark children’s picture book to life – he continues to make and push the boundaries of visual storytelling.

During lockdown, Simpson was working on a pilot for an animated children’s series called Snot Dog after securing funding from the British Film Institute. “It was part of the Young Audiences Content Fund from the BFI and financed by the UK government, which supports the creation of distinct, high-quality content for children and young audiences that entertains, informs and reflects their experiences of growing up across the UK today,” he says.

He created Snot Dog with Jack Land and Shari Clow while Nigel Harris, of JellyBob (Teletubbies), is the executive producer on the proposed show.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We wanted to create an animated children’s series that was made here in the UK and was very British rather than American. We were very grateful to the BFI for the funding. We just need someone like Netflix or Nickelodeon to take it up,” adds Simpson.

Children’s television and books are close to his heart as he has three children aged six, three and five months. In fact, his six-year-old son is the inspiration for a picture book that he is working on at the moment.

“I asked my son what animal he would like to see in a picture book and he said ‘Mmmmmmm Mouse’ and so that’s what I am working on now. I just need to find a publisher.”

Simpson has done a lot and worked with the best when it comes to cartoons and comics, but he still has one dream. “My dream part-time job as a life-long Beano fan would be drawing the Bash Street Kids and Calamity James every week for The Beano.”