Wentworth Woodhouse's 'lost' archives that were thought to have been destroyed in a fire reveal fascinating facts about Yorkshire estate

Yet this urban legend that sprang up in the estate villages as the family’s fortunes crumbled and the Grade I-listed house near Rotherham’s sale approached was never accurate – and a new research project has digitised the Fitzwilliams’ ‘lost’ archives and revealed previously unknown facts about their lives.

The myth was that the 10th and last Earl Fitzwilliam, William Thomas George, burned swathes of records across three weeks of destruction in the grounds in 1972, seven years before his death and the subsequent extinction of the title and direct male line. Rumours spread that he had cast away valuable papers containing the family’s secrets – yet in fact the documents lost had little historical value.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe family’s trove, the Wentworth Fitzwilliam Muniments, had already been deposited for safekeeping to the Sheffield Archives in 1949 – the year after the sudden death of the eighth Earl, Peter, in an air crash, meaning the ‘eldest son’ line of descent had died out and the earldom passed to a cousin. The city archives retain the legal ownership of the cache, and grant staff from Wentworth Woodhouse Preservation Trust access for research purposes.

Yet the Muniments have never been fully catalogued or digitised, meaning the process of transcribing them is time-intensive and difficult.

As part of a long-term project to create an online archive with material scanned in, the Trust offered internships to five Oxford University students, who spent the summer studying manuscripts dating back to the 1700s and curating a new digital collection.

The group were given specific topics about the house’s history to search for ahead of the planned celebrations of two significant events – the 300th anniversary of the 1st Marquess of Rockingham inheriting the Wentworth estates and the 250th anniversary of the Boston Tea Party, which the 2nd Marquess supported.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSteve Ash from the Trust’s digital team said: “The students were invaluable and achieved things which we had never thought of. For example, Meg Burgess showed us a way to scan and digitise items which was much faster than the method our older brains had come up with.

“Nic Nicolaou taught us how to transcribe scanned documents using Optical Character Reading software. He also used Artificial Intelligence software to see how it could provide further efficiencies. The software takes only seconds, rather than several hours, to read the text.

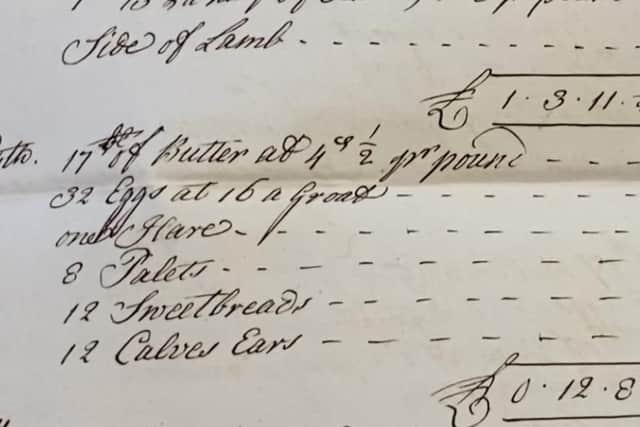

“Reading old handwritten text is difficult, words were spelled differently and people created their own abbreviations. The interns were very adept at it and in addition to digitising more than 600 individual pages, they transcribed over 100 of them.

“Their presence for two weeks also meant the Wentworth Woodhouse Research and Archive Team had additional time to search the archives.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFascinating family letters, documents, receipts and even an architect’s drawing of the Camellia House, currently undergoing restoration, dated 1812 were found. Orders, payment records and invoices from the time of the mansion’s construction revealed not just the huge variety of nails required and how much plasterers and joiners were paid, but also that women were employed on the site as construction labourers.