Kiplin Hall: Yorkshire's 'hidden gem' of a country house that's looking to the future

Kiplin Hall, near Richmond, narrowly escaped demolition in the 1950s, but was given a last-minute reprieve and re-opened to the public following decades of tentative restoration.

The rejuvenation of its once-extensive grounds is still an ongoing project, and as a result this charming Jacobean estate has a homely, rustic feel that's worlds away from the slickly-marketed, grander country houses that have established themselves as major visitor attractions.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdUnusually, Kiplin Hall is managed privately by a charitable trust - the National Trust weren't interested in taking it on - and staffed mainly by volunteers, who are referred to as the 'fifth family' to care for the house, having inherited their responsibility from the four dynasties who lived there until it fell into post-war dereliction.

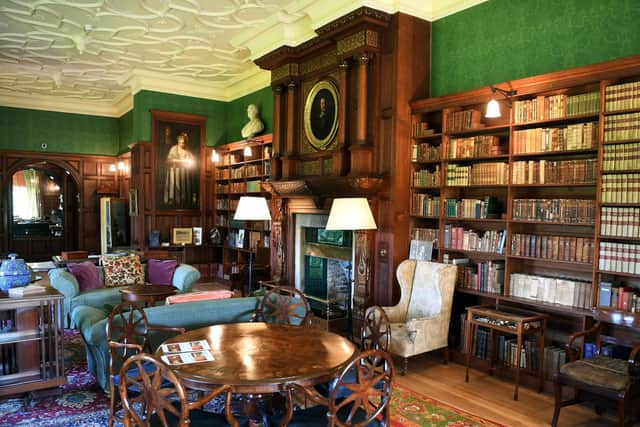

After first opening its doors to visitors in 2000 - the restoration was funded by gravel quarrying in the grounds, although the old pit has now become a scenic lake - Kiplin remained somewhat off the beaten track, with local retirees and students from the University of Maryland - Kiplin's first owner, George Calvert, founded the American colony of Maryland in 1632 - making up the bulk of those touring its 18th-century rooms. The impressive library is the unexpected final resting place of a surprising piece of history - the chair from Lord Nelson's cabin aboard HMS Victory. It was donated by the doctor who treated Nelson before he died in the Battle of Trafalgar, a man who returned to live in Catterick after the Napoleonic Wars and was a frequent visitor to Kiplin.

Following a staffing restructure in 2018, Kiplin's management are on a mission to make the estate more accessible, more family-friendly and more fun.

Olivia Butterfield is a member of the front of house team, who are committed to expanding the range of activities and events on offer.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"There are benefits and disadvantages to being owned by a private trust. We don't get the same publicity as National Trust houses, and we have to run our own events.

"We want to attract more families - our clientele have mainly been of the older generation, so we want to be more accessible to children. It is a very homely and welcoming house - when you walk in it feels as if the family has just left. Most of the objects on display belonged to the families that lived here - very little has been brought in from elsewhere."

The delightful tearoom serves dishes made using fruit and vegetables grown in the walled garden, and customers can eat there without paying the hall entrance fee.

"In summer we sell produce from the kitchen garden. We are restoring the gardens and trying to improve access - we've just laid some new paths suitable for wheelchairs and pushchairs, and we are looking at funding to resurface the path around the lake."

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis summer a Victorian conservatory has been rebuilt in the style enjoyed by the Carpenter family in the estate's 19th-century heyday, and a zip wire will open for younger visitors. Children will also enjoy the nautical-themed play area, pond-dipping, orienteering trails and bushcraft activities.

"We are starting to get the sort of visitors we didn't used to attract. We've started to be a lot more active on social media now, as our staff have the skills and knowledge. We're a bit of a hidden gem really."

Over 100 volunteers work alongside full-time staff to develop the hall in its new era.

"The volunteers are the lifeblood - we call them the 'fifth family' to live here. It would be impossible to operate without them.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"We're currently restoring the gardens to their previous state based on archive records. Ten years ago there wasn't even a walled garden - it's been restored completely, and we've recently re-planted an apple orchard that only had one tree remaining."

In 1958, Bridget Talbot, the house's final owner, had resigned herself to saying goodbye to her beloved Kiplin Hall, where she had spent many happy childhood holidays. She was on the verge of hiring a demolition firm when she was knocked down by a car on a pedestrian crossing in London. Hospitalised with a broken leg, she didn't make the phone call that would have sealed the house's fate. She died at Kiplin in 1971, leaving its contents to the trustees.

A brief history of Kiplin Hall

George Calvert built Kiplin as a hunting lodge in the early 1620s. He was from a wealthy Catholic family and served as secretary of state to King James I. He later became the first Baron Baltimore and founded Maryland in 1632, after becoming disillusioned with the climate of Virginia and petitioning the government for more land. His son Leonard was Maryland's first governor.

The house remained with the Calverts until 1722, when George's great-grandson, the fifth Lord Baltimore, sold it to his mother's second husband, a diplomat called Christopher Crowe. The couple made many Georgian additions to the home, including a servants' wing, and made it their residence.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1818, Christopher Crowe's daughter, Sarah, inherited. She married into the Carpenter family - her husband was the fourth Earl of Tyrconnel. The couple added the gothic library but had no children, so were forced to choose an heir from more distant relations. They settled on the Earl's cousin, Admiral Walter Talbot, a younger son of the Earl of Shrewsbury. As a condition of his inheritance in 1868, Talbot had to change his name to Carpenter.

The hall enjoyed its golden years under Admiral Carpenter's ownership and many of the items on display today date from this period. The Admiral died in 1904 and his daughter Sarah rented the house out to tenants, selling much of the estate land. It was requisitioned by the army during World War Two and used as a munitions dump. By the end of the war, it was derelict and threatened with demolition. Sarah sold the hall to her cousin Bridget Talbot, who was determined to save it. She set up a charitable trust in the 1960s, and secured its future by agreeing to gravel quarrying in the parkland. Restoration of the hall didn't begin until 1998.