Votes for women: The forgotten struggle of Yorkshire’s working-class suffragettes

In 1909, Lady Constance Bulwer-Lytton was interned in Holloway Prison after demonstrating in favour of women’s suffrage at the House of Commons.

As soon as the authorities discovered she was the aristocratic daughter of Robert Bulwer-Lytton, First Earl of Lytton and former Viceroy of India, her release was immediately ordered.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJust one year later, Lady Constance disguised herself as a working-class London seamstress under the name ‘Jane Warton’, and was arrested in Liverpool after an incident of throwing rocks at an MP’s car.

As ‘Jane Warton’, Lady Constance was imprisoned in Walton gaol for 14 days of hard labour and was violently force-fed eight times, a practice commonly used on suffragettes who went on hunger strikes in prison.

Her actions were calculated to highlight the stark difference in the way that working-class and middle or upper-class suffragettes were treated by the authorities, often suffering greater violence and mistreatment in prison.

This class divide among suffragettes didn’t just reveal itself in prison treatment but also in the movement itself, with thousands of working-class women actually left out of the 1918 Representation of the People Act which we today celebrate as the anniversary of women getting the vote.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn our society’s collective memory working-class suffragettes are often sidelined, with middle-class suffragettes like Emily Davison and Emmeline Pankhurst frequently held up as archetypal of the movement.

Yet the campaigning and actions of working-class factory, mill and seamstress women - many of whom, thanks to its industrialised nature were born and based in Yorkshire - were in fact instrumental to the suffragette cause.

Today, however, much of this work - and the women who did it - have faded into obscurity.

The beginnings of suffrage in Yorkshire

Some have suggested that late 19th century trade union struggles and militant action in the workplace paved the way for later direct action taken by suffragettes for the vote.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBetween 1881 and 1911 the number of women in the workforce grew by 24 per cent, with many of these women joining the low-paid, long-hours “sweated” industries.

The West Riding of Yorkshire was a hub for textile industries in England, and though there were few women in trade unions, it was women who led the charge in the 1875 West Yorkshire Woollen Weavers’ strike.

In the wake of a ten per cent wage cut, 9,000 striking weavers converged in Dewsbury on a bitter February day to listen to a speech on trade unionism. Unusually for the time, it was Batley-born Ann Ellis who stood up as the main speaker.

Even more unprecedented was the fact that earlier in the month, the West Yorkshire Weavers - made up of both men and women - had voted for an all-female committee to represent the group before the Masters Association cartel who had imposed the wage cut.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSadly, Ann Ellis died in the Bradford Workhouse in 1919, and little has been written about her. Yet her actions were not lost on everybody.

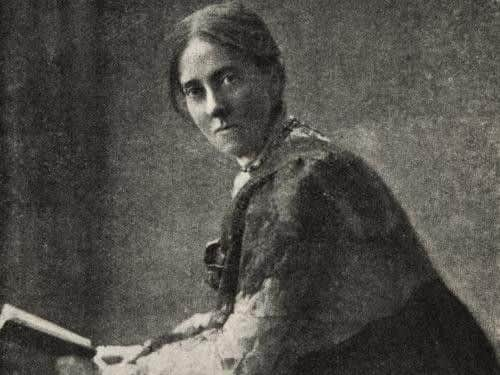

To suffragettes like Leeds-born Isabella Ford, trade unionism and better conditions for women in the workplace were inextricably linked with suffrage - both challenged prejudices about the role of women in society.

At one time, she wrote: “All the orthodox religious world, broadly speaking, is against Trade Unionism for women because Trade Unionism means rebellion, and the orthodox teaching for women is submission in this world in order to gain happiness in the next.”

Who were Yorkshire’s suffragettes?

Though Isabella Ford was herself the daughter of a solicitor, her father ran a night school for local mill girls and it was contact with these women that led Isabella to become involved in trade unionism and later, the cause for female suffrage.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1903, she became the first woman to speak at the annual labour party conference.

Mill worker Dora Thewlis from Huddersfield caught the attention of the press when she was photographed being arrested for her plans to break into the Houses of Parliament along with other suffragettes.

She was just 17 at the time and was labelled ‘The Baby Suffragette’ by the press, with her picture appearing on the front page of The Daily Mirror.

Mary Gawthorpe, however, is perhaps the best-remembered of Yorkshire’s working-class suffragettes. Born in Leeds to a leather worker and a mill worker, like Isabella Ford she became a trade union activist and was later led to the suffragette cause as a result.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlong with Isabella Ford, she set up the Leeds branch of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), and spoke at huge demonstrations across the country, once even being knocked unconscious during a speech. She was imprisoned several times while campaigning for suffrage.

The left-behind working classes

Though early WSPU demonstrations were reported to rely heavily on working-class women, as the group’s actions became more militant and violent it was those with more to lose that were shut out.

As working-class suffragette Hannah Mitchell put it in her memoirs: “No cause can be won between dinner and tea, and most of us who were married had to work with one hand tied behind us.”

For working-class women who were the breadwinners of their household, who had children to feed or simply couldn’t afford to lose respectability in their communities, imprisonment wasn’t worth the risk.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt has been speculated, for instance, that working-class suffragettes like Dora Thewlis who found themselves in trouble with the law just once went quiet afterwards for fear of more serious repercussions like losing a job or a home.

With Yorkshire at the time being an important hub for industrial activity, many suffragettes in the region saw working class struggles (championed by the labour movement) as going hand-in-hand with female suffrage.

The celebrated journalist of the time, Rebecca West, speculated that at the beginning of the WSPU the group had dealt “boldly with the wrongs done women by the industrial system”, yet later shifted focus solely onto the vote.

However, in 1907 the WSPU broke off ties with the Labour Party, and it has been suggested that it was from this point that the group became increasingly dominated by a group of wealthy women.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThough the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), from which the WSPU had originally splintered, was thought to be more accommodating to working-class women, both groups campaigned for the vote on the same basis as men, meaning they’d have to meet minimum property qualifications to vote, shutting out most working-class women.

What’s more, the 1918 Representation of the People Act stipulated that women would have to be above 30 to vote. Given that the majority of working-class women in factories and mills were under this age, the passing of the act had no bearing on thousands of these womens’ lives.

Although it added 8.5 million women to the electoral register, it represented less than half of adult women in the UK.

Forgotten stories

Unlike their more well-to-do counterparts, working-class women also rarely had the time or resources to write memoirs or indeed leave any mark of the work they did for the suffrage cause.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThose who did partake in action often had to conceal their identities in order to avoid losing their jobs and livelihoods.

Because of this, the stories of those working-class women who campaigned for suffrage have largely been lost in time.

It is only recently that historians have begun to look more closely into the contributions of working-class women to the cause in Yorkshire and beyond.

In spite of the middle-class face of the movement, it’s widely accepted that the labour of working class women in regions outside of London, like Yorkshire, was key in spreading the message further afield than the capital.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOften risking far more than their middle and upper-class counterparts, working-class woman presented petitions, marched and took part in other direct action - and when parts of the movement turned away from them, they continued to campaign for universal female suffrage in communities and through trade unions.

And although 2018 was marked out as 100 years since female suffrage in the UK, many are beginning to recognise that for working-class women, the fight was not over until 1928, when

women under 30 without the property qualification were finally granted the vote.