How army of drones and robots could make Leeds the world's first self-repairing city

Leeds, 2035. Moments after scanning a city road and identifying a crack in the surface around the size of a 50p piece on a night-time patrol, a drone navigates itself down to the site of the problem, lands and fills in the defect using a 3D asphalt printer. What could have eventually developed into a serious pothole is fixed instantly and the drone flies off to search for its next assignment.

It is a scenario that, despite the increasing prominence of drones in daily life, still sounds like science-fiction. But for the past three years, a team of robotics engineers at the University of Leeds’s School of Mechanical Engineering have been making considerable progress on turning the concept into a reality as they work on a multi-million pound, Government-supported project to turn potholes into a thing of the past.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLike almost every city and town in the country, Leeds has a considerable pothole problem - with over 10,000 reported to the council by members of the public between 2014 and 2017. But the city could soon be leading the way globally in dealing with the problem, as well as deploying drones to repair street lights and sending hybrid robots to live in utility pipes which they continually inspect, monitor and repair when necessary.

It is all part of a wider scientific ambition called ‘Self-Repairing Cities’ that has the ambitious aim of ensuring there is no disruption from streetworks in UK cities by 2050. The vision for the project states: “With the aid of Leeds City Council, we want to make Leeds the first city in the world that is fully maintained autonomously by 2035.”

Professor Rob Richardson, operational director for the robotics element of the project, says despite the major changes potentially on the horizon, it should not mean drones constantly buzzing over everyone’s heads. “We see them as being like urban foxes,” he explains. “There are not going to be drones over your head constantly. You might see them in particular times of day in particular places but you won’t see them all the time. It wouldn’t be invasive.”

The five-year project, officially called ‘Balancing the Impact of City Infrastructure Engineering on Natural Systems Using Robots’, started back in January 2016 after £4.2m of funding was secured from the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council. It was one of seven ‘Engineering Grand Challenges’ awarded money by the agency to provide innovative solutions to issues such as tackling air pollution.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Leeds scheme is also being supported by researchers from the universities Birmingham, Southampton and University College London, with project partners including Leeds Council, Balfour Beatty, the National Grid and Yorkshire Water.

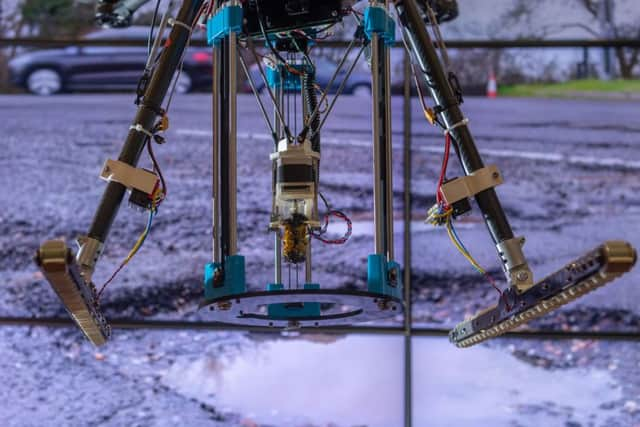

One of the main achievements of the projects to date has been combined work by the UCL and Leeds teams on developing 3D asphalt printing technology - which Richardson describes as a “world-first” - that can be used by the drones. Work is now taking place on developing a scanning and decision-making system for such drones.

Richardson says there are other possibilities for identifying small cracks in the road surface, such as through self-driving cars, buses and bin lorries that would have scanners attached to them as they went about their normal operations in ‘smart cities’ that use electronically-collected data to manage resources such as traffic lights effectively. The system would also allow for temporary road closures if necessary when drones are working on repairs.

The investment of public money is dwarfed by the amounts currently spent on dealing with potholes alone. In last October’s Budget, Chancellor Philip Hammond assigned an extra £420m to local councils for tackling potholes on top of an existing fund of £300m, while the annual cost of resurfacing roads in the UK is estimated to be more than £1bn.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRichardson says the potential benefits go beyond immediate financial implications. “Right now, if you have got a bad pothole, you need people, big vehicles and disruption through closing the road and causing pollution to get rid of it,” he explains. “We want to change that and repair things before they become potholes.”

Richardson adds the current costs for repairing potholes are difficult to estimate. “You can look at the cost of a person and the hours they work to do it. But the real cost is if there are not prompt repairs, roads gets further damaged. If you have to close roads for long periods of time, congestion and pollution builds up. There are wider costs far more than a worker’s hourly rate. Our vision is by 2035 to have this kind of technology in a city, with potentially Leeds being the first one. Our grand vision is by 2050 that the whole of the UK will have self-repairing cities. At the end of the five years we want to show what can be done.”

While such changes may make life better for drivers and council budgets, there would obviously be an impact on employment as technology may make many jobs redundant. The hope is for a “win-win situation” where better jobs are created, taxpayers’ money is used more efficiently and our air, water and wildlife are protected - but a mid-term report examining the progress of the project to date has suggested it may not be quite so simple.

“In the past, every industrial revolution has seen existing jobs become obsolete, labour being replaced with machines, and yet new tasks have emerged that acted as a counterbalance to the displacement of workers,” it says. “Similar to the past, the robotics and AI revolution is set to displace a large proportion of the current workforce. But the concern this time is that if robots/AI can learn most of the new tasks, the creation of new jobs may not be a sufficient counterbalance for the loss of obsolete ones. With uncertainty writ large over this revolution, it will be the responsibility of the state to safeguard the interest of all members of society and make sure that those who stand to lose the most from impending disruptions do not fall through the cracks.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe major disruption at Gatwick airport around Christmas in which drone sightings grounded about 1,000 flights raised public concerns about the use of the technology. Leeds and Southampton universities have already been working with the cities of Bradford and Southampton to identify potential challenges and risks and find a safe way of overcoming them.

Drones have been used to provide real-time information to firefighters in Bradford to give early warning of structural problems and identify hotspots and people in need of help at incidents.

Richardson says: “Smart cities currently check data and understand people flow. That doesn’t do proactive systems. But we are talking about cities that are able to understand what is happening and be able to react and do things.

“All of this stuff is overseen by people, they are systems based on a framework set and regulated by humans. As with all technology, regulations are there for a reason. If it is done correctly, it brings good.”

Project achievements growing

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAchievements of the project so far include creating technology to 3D print asphalt which is tougher than ordinary asphalt and demonstrating that a printer can be attached to a drone, flown to a damage location and operated.

Other developments include an inspection robot that can operate autonomously in a one-inch pipe, with wireless power transfer for charging and the simulation of how cheap ‘disposable’ robots can efficiently locate potholes or other defects in roads. A spokesman said: “The findings will be used to develop the next generation of robots for infrastructure inspection and repair, but with applications in any field that might benefit from the introduction of robotics and autonomous systems.”