Battling Bridget’s war effort

If the Ministry of Defence could have worked out how to clone Bridget Talbot, the Second World War, if it had started at all, would probably have been over in a matter of weeks. Hitler simply wouldn’t have stood a chance.

By the time of her death in 1971 at the age of 86, she had served on the frontline during the First World War, bent the ear of successive generations of politicians, helped to house hundreds of political refugees and for good measure had invented a device which saved the lives of thousands of military personnel. To those that knew her when she was the owner of Kiplin Hall in North Yorkshire she was also unapologetically eccentric.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“She had a car, an Austin Ruby, which she took to painting herself,” says Dawn Webster, curator of the property. “Sometimes it was yellow, sometimes it was blue, sometimes it was white. Sometimes she didn’t bother finishing the next paint job, so it was a mixture of all three.

It meant she was very visible whenever she drove into Richmond to meet friends at the Talbot Inn, more often than not abandoning the car in any spot which was convenient to her, but generally massively inconvenient to other traffic.

“There’s a story of the local policeman coming into the pub to tell her she couldn’t possibly leave her car on the main route in the town. ‘Ok,’ she said handing him the keys. ‘You move it and just tell me where you’ve left it’.”

In her latter years, those idiosyncrasies perhaps belied a woman who was a ruthless campaigner and tireless activist for those whom society had denied a voice. Bridget Talbot was a one-off and her life and times form part of a new exhibition at Kiplin Hall which throws a spotlight on Yorkshire’s country houses and the individuals who ran them in war.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDuty Calls is a joint project between eight properties in the county which belong to the Yorkshire Country House Partnership. Running until October next year, when the country will mark the centenary of the First World War, at the heart of the Kiplin Hall exhibition is the story of Bridget based largely on her detailed journals and extensive correspondence.

The second child of Alfred Talbot and Emily de Grey, Bridget had an idyllic childhood in the Hertfordshire village of Little Gaddesden and could easily have continued to live a comfortable upper middle-class existence. However, from an early age there was something that propelled Bridget into the political arena. By her early 20s she was already flexing her campaigning muscles and the outbreak of the First World War only served to deepen her resolve.

When Belgian refugees began fleeing to England after the German invasion of August 1914, Bridget was on the London committee which organised depots at Alexandra Palace and Earls Court to provide emergency housing.

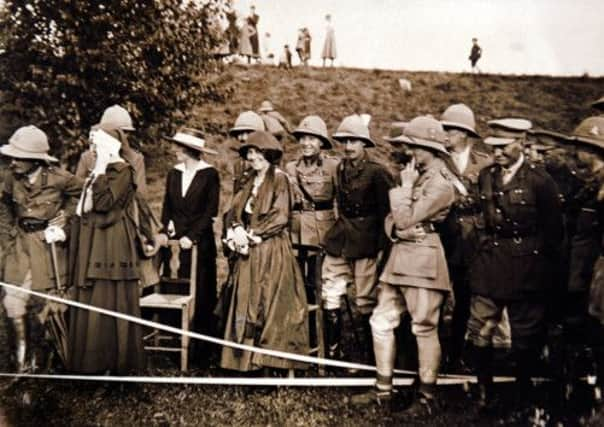

Some would have been content to do their bit on the home front, but two years later Bridget had packed a few bare essentials and was travelling through France on her way to the Austro-Italian border and the heart of the war zone. There the death toll on both sides was mounting and alongside another force of nature by the name of Mrs Watkins, Bridget helped to set up aid stations and canteens at Cervignano and Cormons. While she had some basic training in home nursing and first aid, what she lacked in technical skill she made up for in sheer enthusiasm and resilience and when the Red Cross took over the operation, Bridget remained a driving force, tending to the wounded before they were transferred to one of a number of military hospitals. In April 1918, she wrote that in just six months 50,000 injured men had passed through their makeshift triage.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA spell working with Russian refugees in Turkey followed and when she finally arrived back in England she had won numerous medals and accolades but Bridget also returned with a burning sense of injustice.

“Her experiences during the First World War really did colour everything that she did afterwards,” says Dawn. “We can only imagine some of the horrific sights she saw out in Italy. It was character forming and she never stopped fighting for those less fortunate than her.

“Bridget was one of the few women of privilege who began life as a committed Tory, switched to become a fully paid up member of the National Labour Party in the 1930s, stood for the Liberal Party in 1950 before putting herself forward as an independent candidate for Richmond in the 1964 General Election. I think that tells you a lot about her life and her beliefs.”

During the Second World War Bridget campaigned tirelessly to ensure the safety of men serving with both the Merchant and Royal Navy. She wrote to newspapers calling for conditions for seamen to be improved, she raised questions in Parliament and despite having no background in engineering, she also invented a waterproof torch. Not satisfied with having her name on the patent documents, she also badgered Government Ministers to ensure they were given to all Merchant Navy, Royal Navy and RAF personnel.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“So many men had been drowned in the First World War and Bridget knew that those who were lost overboard would stand a much better chance of being rescued if they could make themselves known to rescuers,” says Dawn. “Like a lot of the best inventions it was simple, but revolutionary.”

It was shortly before the Second World War that Bridget’s cousin Sarah Turnor made her joint owner of Kiplin Hall. Sarah was struggling to find a use for the sprawling estate and reckoned rightly that Bridget would be useful to have on board.

When war broke out, the military were keen to requisition as many large properties as they could and it was under Bridget’s direction that from late 1939, Kiplin Hall was given over to the Army

In June 1940 it was the destination of men from the 1st Battalion The East Lancashire Regiment, who had been rescued from the beaches of Dunkirk.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“All day and all night straggling and exhausted men arrived,” reads one account of the period. “The owner did everything that was possible in the way of collecting food, blankets and cushions and by three the next afternoon every floor was covered with men sleeping as if dead.

“It was a sight never to be forgotten with the hot sun streaming in at the windows onto the pictures, old furniture, the walls of books and the floor a silent carpet of prostrate khaki figures. With the help of a little gardening, bathing in the river and sleeping these Dunkirk men gradually recovered from their weariness and mended their shattered nerves.”

Two years later, Kiplin was requisitioned by the Royal Air Force as a supply base in the north of England. Its grounds became home to a stockpile of bombs and ammunition which would be sent on to local airfields, in particular Bomber Command at Middleton St George and Croft, although Bridget drew the line at storing ammunition in the Hall’s cellars.

“By 1944, the number of bombing raids on Germany and France increased enormously and the unit’s turnover of explosives had to double to meet the demand,” says Dawn. “Everything was done on a needs must basis and like a lot of similar properties, Kiplin Hall did take a bit of a battering. These were places which were used to hosting quite genteel occasions and all of a sudden dozens of soldiers were trooping through their corridors.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs well as Bridget’s letters, the exhibition includes the flight logbook of her younger brother Geoffrey Talbot, who was killed in 1916 when his wood and canvas plane crashed after becoming caught in a gust of wind, displays on the 400-year-old hall’s links to the Civil War as well as memories of those who lived on or close to the estate in the 1930s and 40s.

“People often say if only the walls of these historic properties could talk...” says Dawn. “Well, hopefully this exhibition will allow them to do just that.”

Duty Calls exhibition highlights

Beningbrough Hall, York

Requisitioned as a billet and mess for the Royal Canadian Air Force, the property will showcase the stories of the men and women who stayed there during the Second World War.

Brodsworth Hall, Doncaster

Exploring life on the estate in both world wars, the exhibition includes letters from men in the trenches thanking a local schoolgirl for knitting them garments.

Castle Howard, North Yorkshire

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGenerations of Howard sons went to fight overseas, but the Belgian refugees, enemy prisoners evacuees and crashed aircraft meant the impact of war was often more powerfully felt at home.

Fairfax House, York

Focuses on the Jacobite rebellions of 1715 and 1745 in an exhibition which also marks the 250th anniversary of the Georgian property.

Lotherton Hall, Leeds

Traces the long history of Lotherton Hall and the Gascoigne family, from the American War of Independence to the Second World War, via Lotherton’s use as a military hospital in the First World War.

Newby Hall, Ripon

A look at how the property was earmarked as a secret refuge for the Royal Family during the Second World War.

Nostell Priory, Wakefield

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLooks at the impact of war on both the rich landowners and poor farmworkers.

Sewerby Hall, Bridlington

Contrasts the experiences of the Lloyd Graeme family and their estate workers during the First and Second World Wars.

For full details go to www.ychp.org.uk