Boots tell incredible story of Antarctic survival

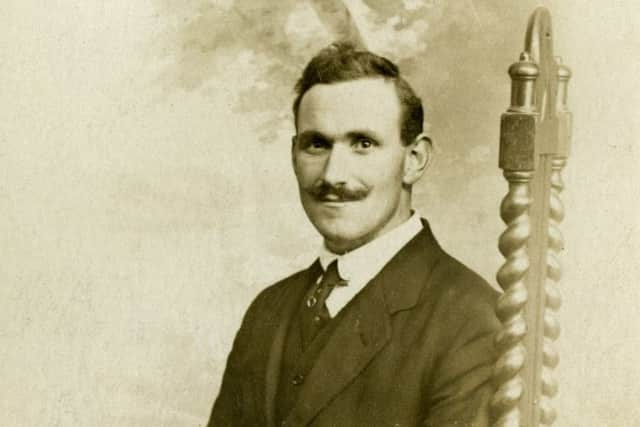

The crumpled leather footwear belonged to John Vincent - one of the five men Ernest Shackleton picked for a hazardous open boat journey to try and get help, after their ship the Endurance became trapped in ice in 1915 and sank 10 months later.

Vincent, from Hull, had been a fisherman and was well used to harsh conditions.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe was seen as the fittest member of crew, but by the time they got to South Georgia after an 800-mile journey, he was physically and mentally done in and may have been suffering from trenchfoot.

His boots are being put on display for the first time in decades as part of an exhibition, showing the amazing pictures taken by Frank Hurley, during the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914-1917.

The fragile glass plate negatives were saved from the sinking Endurance and carefully preserved in the collections of the Royal Geographical Society (RGS).

One hundred years later they remain one of the greatest photographic records of human endurance.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlong with Vincent, there were four others from the city on the expedition - fourth officer Alfred Cheetham, seven years older than Shackleton and the man considered to have the most Antarctic experience, firemen William Stephenson and Ernest Holness, and “sooty faced cook” Charles Green. Green, who in his later years was an attendant in East Park, is still remembered locally.

As The Yorkshire Post recorded “behind his enigmatic expression lay memories of unimaginable adversity: that kindly Mr Green had once drawn lots with 23 starving shipmates to see who among them should be killed and eaten.”

Stripped of his galley, when the ship sank, Green was nothing but resourceful and his “cheerful grin never deserted him” as he whipped up a “splendid hot meal of hoosh or seal meal in 35 minutes from lighting the blubber fire”.

After the last Shackleton expedition in 1921, Green went back to sea again, and addressed audiences as far afield as the US, Canada and Hong Kong.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSettling in Hull, he continued to give talks locally, with 110 lantern slides he had been given by Shackleton.“Hull has always been the source of Polar explorers because we were one of the biggest whaling ports at one stage and the seamen were used to Arctic waters,” said the museum’s assistant curator Tom Goulder.

“The Arctic expeditions took Hull men and that tradition carried on with the Antarctic expeditions. They all volunteered to go - it wasn’t necessarily for the wages, it was for the adventure.”

Enduring Eye: the Antarctic legacy of Sir Ernest Shackleton and Frank Hurley is at Hull Maritime Museum from March 3 to June 3.