Headingley 1975: When vandals stopped play

FORTY years ago today saw an incident that remains unique in the annals of sporting history. It was on the early morning of August 19, 1975, the fifth day of the third Ashes Test match, that the groundsman at Headingley cricket ground arrived at work to discover that the pitch had been targeted by vandals. The combination of holes dug in the wicket and oil poured on its surface meant that the match would have to be abandoned.

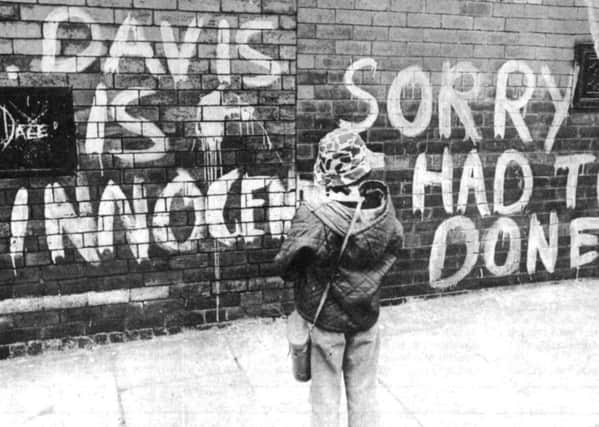

It was immediately apparent from the accompanying graffiti at the ground that the damage had been caused by the friends of a man called George Davis, who was in jail for an armed raid on the London Electricity Board in 1974 – a crime, they argued, that he did not commit.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdUp to that point, the cricket had been enthralling. Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson tearing into the England batsmen; the two brave half-centuries from David Steele; Phil Edmonds’s five-wicket haul on debut; the stunning catch by Thomson to dismiss Alan Knott in England’s second innings... At the end of the fourth day, Australia, chasing 445 to win, were making more than a reasonable fist of it at 220 for the loss of three wickets.

It was on the Tuesday morning, just as I was setting off to meet my friend to catch the bus to Headingley, that my mother suggested I might wish to listen to the radio news. It was announced that, as the pitch was unfit for play, the game would have to be called off. My mother queried this: surely they could just move a little further along the square and set up the stumps there?

All these years later, the recollection is that my immediate feelings were not so much of anger or resentment, but of an overwhelming sense of void and emptiness. What I cannot recall is the weather. It was not until many years after the event, when I read Ken Dalby’s Headingley Test Cricket 1899-1975, that I realised that “steady rain would almost certainly have prevented play in any case”.

The campaign organised on Davis’s behalf was successful. He was released from prison in May 1976, the Home Secretary Roy Jenkins having formed the view that his conviction was unsafe. Davis rewarded his family and friends with his involvement in an armed robbery in 1977 for which he was sent to jail the following year. After his release from that sentence, he was jailed again for another crime in 1987.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe passage of time allows one to put the 1975 Headingley Test match “outrage” – as it was described in the following year’s Yorkshire CCC annual report – into some sort of context. Within the UK sporting environment, it remains highly unusual for two reasons: the motive for the protest and the impact on the event being targeted.

First, the motive. I would hazard a guess that the vast majority of protests at sporting events in Britain are related to one of the individuals or teams participating at the event itself, usually reflecting disgruntlement about management and/or ownership.

Examples during the last football season included the boycott by some Newcastle United season ticket holders and the pitch invasion on the last game of the season by disgruntled supporters of Blackpool. There is a clear distinction to be made between a protest and naked football hooliganism as evident at, for example, the abandoned football friendly in Dublin between England and Ireland in 1995.

In cases in which the causes of the protests are non-sporting, they have often been for reasons that concern politics or religion, albeit with some variations in the clarity of objective. The most famous example is that of Emily Davison throwing herself in front of the field of the 1913 Derby in the cause of female suffrage.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMore recent instances of individual protest include a former Roman Catholic priest, Neil Horan, proclaiming that the end of the world was nigh as he ran across the Silverstone track waving a banner during the 2003 British Grand Prix and Trenton Oldfield’s wail against “the culture of elitism” in British society after he had been fished out of the Thames at the 2012 Boat Race. That both Horan and Oldfield avoided the fatal consequences that befell Davison is, in itself, a minor miracle.

Local grievances have also been a cause of protest. There are several examples of disgruntled locals objecting to road closures for cycle events by covering parts of the routes with carpet tacks and drawing pins, including the Etape Caledonian in Perthshire in 2009 and the Etape Cymru in North Wales in 2013.

However, with the striking exception of the continual disruption of the 1969 South African rugby tour by anti-apartheid demonstrators, any sizeable political protest at sporting events in Britain has been absent.

By contrast, the George Davis case remains a rare example of direct action being committed with the aim of disrupting or bringing to an end a major sporting event in Britain for what are essentially personal reasons.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOther instances are hard to find, though one such case occurred in 2012 when a man called John Foley handcuffed himself to the goalpost during an Everton and Manchester City match in protest at his daughter’s dismissal by a budget airline. Seven years earlier, members of the Fathers 4 Justice campaign group climbed on to the roof of the Crucible Theatre in Sheffield during the Embassy World Snooker Championship.

In the case of the George Davis protest, however, there was one crucial difference. The actions of his supporters had the effect of ending the Test match – notwithstanding my mother’s suggested action.

This was unlike the other examples referred to here: the 1913 Derby ran its course; the Grand Prix drivers were slowed down by a safety car before resuming the race; the Boat Race was only temporarily halted; at Goodison Park, the football match was delayed for a few minutes; the snooker was unaffected; the cycling in Scotland resumed after an hour-and-a-half; the 1969 Springboks completed their itinerary in full.

By contrast, the England-Australia scorecard in the Yorkshire CCC annual report of 1976 was soberly headed “Match drawn (Pitch violated)”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe report argued that: “It is easy to be wise after the event and plan the security devices which might have been employed. It is less easy to anticipate the actions of the mindless few who will go to any length to draw attention to a cause, however good or bad”.

This was a fair standpoint, though I am not sure “mindless” fitted the bill: Davis’s supporters knew exactly what they were doing. The main lesson from the Headingley Test episode of 1975 was to confirm that significant damage could be wrought by those armed with a straightforward plan, simple tools and a perverse imagination. It remains the case today and is a corollary of living in a liberal democracy in which civic conduct is based on mutual trust.

John Rigg is the author of sporting memoir An Ordinary Spectator.