How traditional rope making in Yorkshire is helping lasso queues of sightseers

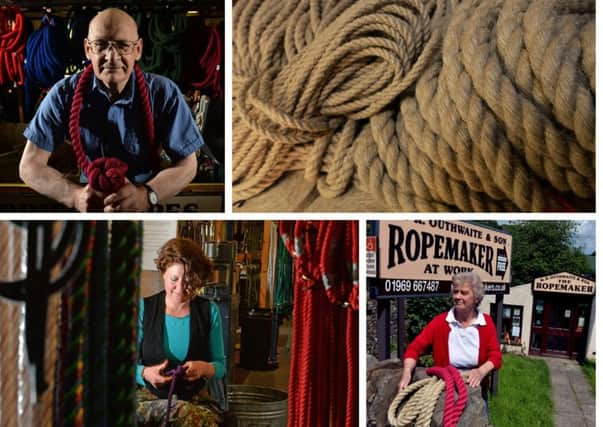

The picturesque Dales market town of Hawes is famous for its crumbling white Wensleydale cheese and its auction mart specialising in Swaledale sheep. But there is another celebrated must-see – how it has lassoed queues of sightseers for 40 years, their interest piqued by the unusual. Going from strength to strength since it found a new lease of life in 1975, Outhwaites is one of the few traditional rope makers remaining in England when once there were thousands.

Styled to match the former Victorian railway station that stands adjacent, it is attracting coach tour passengers as I arrive, all of us making a beeline for its entrance. “Clock that sign. See how the twist is put in... Cool,’” says one of them.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe factory stands by a beck called Blackburn Syke where delicate pale blue forget-me-nots bloom along the banks. In centuries gone by many a village had its own rope maker as well as a cobbler and blacksmith, Hawes being no exception.

John Brenkley, of neighbouring Sedbusk, is listed in Askrigg church records as being a rope maker at the time of his death in 1725, and during the 1800s, the Wharton family made ropes in Hawes, followed by the Outhwaite family until 1975.

Then it was that the firm began to enjoy a new lease of life in the capable hands of a far-sighted couple, former college lecturers Peter and Ruth Annison.

Peter, originally a textile chemist, sadly died in April, but Ruth continues to see her late husband’s work live on.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen the couple took over the ropeworks in the year that the first two Britons climbed Everest, they faced a daunting task. Yet like Doug Scott and Dougal Haston who succeeded in scaling the world’s highest mountain, the Annisons had done their homework.

Roped up together, how they refreshed the old firm with new ideas. Two strokes of good fortune helped. Previous rope maker Tom Outhwaite, Ruth remembers, was delighted to spend time showing them the ropes.

James Herriot’s vet books were starting to sell worldwide too in the 70s which brought in thousands of fresh visitors eager to experience the flower-rich walks and meet real Dales characters. They visited the ropeworks, too.

Records of visitor attendances reveal the thousands visiting Outhwaites have always been keen to see traditional methods. So frequently did they ask for rope souvenirs, Ruth tells me, that the Annisons saw the potential in fulfilling this demand. They invested in modern hi-tech machines from overseas and widened their range with rainbow-coloured skipping ropes and macramé knotted plant pot hangers proving ready sellers.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOther products like rope handles for jute shopping bags, anorak cords and light pulls – all far removed from the heavier-duty ropes made for agriculture, forestry and so on (still produced on the rope-walk) – kept the tills pinging.

Norman Chapman, who I meet on the shop floor, was the Annisons’ third stroke of luck. In 1975 he was driving a lorry delivering animal feed to farms, but was looking for a new job. Not easy in Wensleydale where jobs were mainly based on farming or the building trade.

The Annisons duly took Norman on, even though he had told them the only knot he knew was the wagoner’s hitch.

Over the following 40 years he became head rope maker and introduced many members of the present staff to rope making.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlthough he retired four years ago, this well- regarded ambassador in the rope-making world gladly accepted Ruth’s invitation to show readers of The Yorkshire Post Magazine the ropes.

“Are hawser-laid ropes so-called because they are made in Hawes?” I asked.

He gave me an old-fashioned look. “In a word, no.” Norman’s domain was the rope-walk.

It is here that it all comes back to him on his return: how strands of yarn stretch out along the length of the building, quivering and taut as they are twisted into ropes.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen I mention the length of the rope-walk, Norman says: “You should see the one at Chatham’s historic naval dockyard. There the rope-walk stretches for hundreds of feet. Rope makers need bicycles to cover the distance.”

In Hawes, the rope-walk is 82-feet long, so capable of making lengthy ropes as used for agriculture.

Conversely, ropes can be cut up into shorter lengths, ideal for barrier ropes, bannister ropes and dog leads.

Rope making still employs centuries-old techniques – a discernible advance being an electric motor that speeds twisting the separate strands during production.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNorman is patience personified as he explains the basics of traditional rope making. “First,” he says, “we begin with what we call ‘warping-up’.” Strands comprising countless yarns are stretched out along the rope-walk – like the rubber bands in a model aeroplane that drive the propeller.

“These three separate strands are each anchored at one end to their respective hooks arranged as for a game of wall hoopla. Each of them revolve.

“They are driven round and round by what is called the ‘fixed head’ twisting machine to which they are attached.

“As each hook rotates, it twists its individual strand in its entirety before all three strands then start laying over each other in the final stages to make the rope we sell on the shelves.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“To complete the warping up process, the rope maker walks to the rope-walk’s other end so seemingly far away. There he will fix the far end of the three strands to a single hook which is attached to a heavy sledge weighted with breeze blocks.”

“A heavy sledge?” I repeat, chipping in. “Like an Olympic Games bobsleigh...”

Norman laughs. “Not quite! Let’s just say it only moves when towed along.”

He pauses while I take this in. “After the motor is switched on and starts twisting the strands, the effect is like hair being braided into a plait.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The more twisted the strands become, they get shorter in length. It’s this effect that then begins to drag the sledge in its wake.”

“So that is how the twist is put in,” I mutter. Norman nods as I absorb this Eureka moment.

“To prevent the strands becoming jumbled at the crucial point where they begin to lay over and form the rope, the rope maker walks alongside. His sole job now is to keep apart the three strands that are still separated for as long as possible by using an age-old instrument called a ‘top’.

He shows me a gadget shaped like a large wooden computer mouse, much polished by constant use. It is incised with deep grooves. These each accommodate a strand – as if slotted in between the fingers of an outstretched hand.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Keeping the strands apart until they finally merge into the single rope is crucial,” says Norman. “The wooden top is the secret. Without it, things can get very tangled. Once the rope is forming turn by turn behind the rope maker, and it starts towing the sledge behind, things can be said to be proceeding.

“When the rope is completely laid together, all the 82ft distance from sledge to the fixed head machine, the rope maker switches off the machine.”

“So that’s it?” I ask. “That’s it,” he says. “Welcome to a factory-fresh, hawser-laid cotton rope from Herriot land. Warping up and collecting the finished product is a never-ending task, but it’s wonderfully satisfying to coil a pristine new rope.”

There are machines nowadays that can make hawser-laid rope, neatly coiling a newly-made rope like Norman must have done a million times before.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“To say they will signal the end of the rope-walk is an interesting comment. But I prefer to see the bigger picture. As long as there is a demand for the ropes we produce I’m sure Outhwaites will continue fulfilling it.

“Traditional rope making will go on for a long time yet.”