Andrew Vine: A wooden box's story of pain and sacrifice as First World War, and its legacy, is remembered

They are the only memento I have of my paternal grandfather, and the hammer, the last, the knives and the awl for punching holes in leather tell one small story of the Great War.

He was shot and badly wounded on the Western Front. His life was saved, but blighted. He could only stand or walk with the aid of crutches and was never free of pain. The country he had been fighting for had little compassion, and no practical assistance to offer when he was brought home. Offensively to our sensibilities today, he was termed a cripple.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

He could not return to his pre-war job as a miner, the privately-owned pits had nothing else to offer a wounded ex-serviceman and there was no welfare state to help him, his wife, and four children, nor a health service to ease his pain.

So he bought the tools, knocked together a box for them from some bits of wood he scrounged and scratched a meagre living mending shoes, because he could do that sitting down.

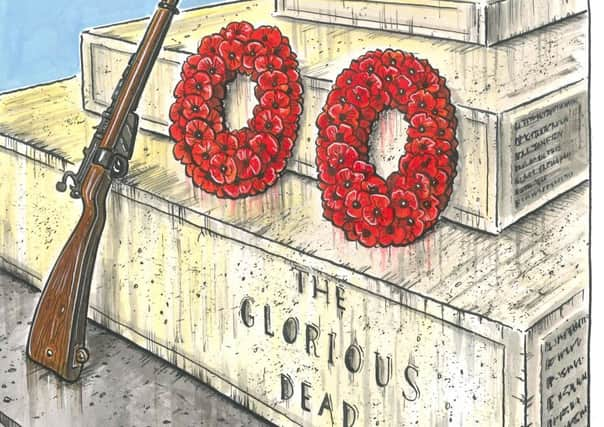

I never knew him. He died long before I was born, his health fatally compromised by his wounds and his spirit ground down by endless pain. Because he survived the war, his name is on no memorial other than his gravestone.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere are no pictures of him, because to a family in poverty, a camera and film were out of the question, and there would have been nothing to smile for in a snapshot anyway. The box of tools is all that’s left, an odd and poignant reminder of a life that in the instant he was riddled with bullets became unbearably hard.

Thousands of other families will have their own mementoes that speak to them as personally as my grandfather’s few poor belongings do to me. Maybe medals, maybe letters, maybe a photograph in uniform, each precious beyond monetary worth and freighted with emotional significance, to be passed down the generations along with the story it tells.

He’ll be in my thoughts tomorrow, even though I have no means of summoning up how he looked, how he spoke or any idea of his personality.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRemembrance Sunday always makes me think of him, and wonder what he was like.

All over the country, as people bow their heads at 11am, other people will wonder too about their own relatives, what they did, what they saw, how they suffered, and if they lived, how they coped afterwards.

And to wonder is to honour their memories, because we are engaging with them. Even though, in many cases, a century or more separates us from them, the generation that fought the Great War are going to seem powerfully present tomorrow.

The centenary of the Armistice has brought remembrance more sharply into focus than at any time for decades. Four years of sombre, dignified commemorations since 2014 have been building up to this moment.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAwareness of what the war involved, the sacrifice of those who died and the mark it left on the lives of those who survived has been heightened, especially amongst the young and that is something of which our country should be proud.

One of the most moving things I have ever seen took place in the colossal Tyne Cot war cemetery and memorial to the missing in Belgium last year, as the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Passchendaele approached.

A party of schoolchildren laid a wreath at the foot of one of the panels commemorating the fallen whose remains were never found in that hellish, blasted landscape of churned mud and poison gas. Then they bowed their heads and wept.

There was no artifice in their grief, no forcing the tears to come. The sheer visceral impact of the loss represented by the memorial, with its tens of thousands of names, had a profound effect on the children.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA year before, as Britain prepared to commemorate the centenary of the start of the Battle of the Somme, there were similarly touching tributes apparent at the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing. Photographs and wooden crosses with poppies had been left alongside specific names, and there were written tributes from schools.

Some were from Yorkshire, where the Somme holds a special, terrible place in our collective memory because of the slaughter of the volunteer Pals battalions from Leeds, Bradford and Barnsley on its first day.

The children could have no more actual knowledge of these men than I have of my grandfather, yet they cared enough to pay tribute to them. They had learned the value of remembrance and the obligation on us all to never forget. A tremor of anxiety has run through the past four years of commemorations, and it can be felt about tomorrow’s centenary. It is that once this milestone anniversary is past, the Great War will somehow be forgotten, and its sacrifice not adequately honoured in the future.

We need have no worries on that score. The children I saw in France and Belgium had learned a lesson in remembrance that they will never forget. In time, they will pass it on to their own children.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAdults have learned too. There are more people touring the Great War battlefields now than at any time in the 30-odd years that I have been visiting them, and it is noticeable how many more family groups there are, generations discovering their collective history together.

Books about the war sell in vast quantities, and huge audiences watch television programmes. Attendances at Remembrance Sunday events have risen, and the number of poppies the Royal British Legion sells increases every year.

Britain has embraced the importance of remembrance ever more closely over the course of these past four years. Tomorrow is a culmination of that. It is also a promise that we shall never, ever forget.