Pushy parents who tweet teachers: It’s their own time they’re wasting – David Behrens

This would be fine if those at the receiving end of all the complaints had nothing better to do than deal with them. Many companies have indeed put in place teams of people to do just that. Some are good at it, adopting an appropriate tone of voice to defend the corporate honour. Others – I’m thinking of Northern Rail in particular – manage only to come across as petulant and offensive.

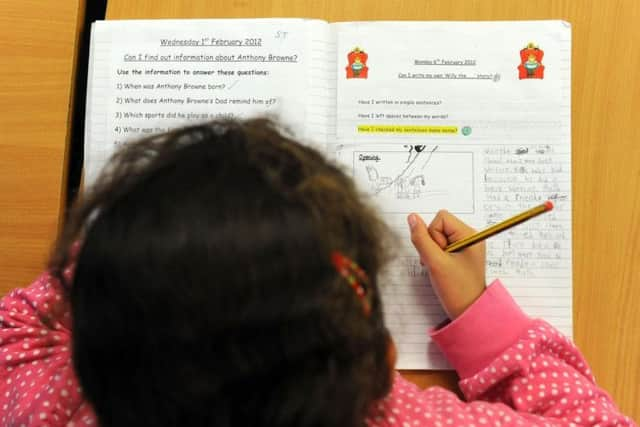

For most of us, though, an avalanche of unwanted correspondence of dubious provenance is an imposition. This is particularly true of teachers, who get enough grief from their pupils without having to engage in playground squabbles with their parents.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe schools inspectorate, Ofsted, highlighted this week the undue power that social media has handed parents to publish negative comments which compound the profession’s worryingly high stress levels.

One teacher likened the daily inbox to a “pit of death”; others complained of “incessant” messages, often at night, from parents who felt a right of access, mistaking a school’s presence on Twitter for an open door.

We’re not talking here about intellectually challenging levels of debate, of deft wordplay or cutting badinage, but of inappropriate and often aggressive comments that would never be made to someone’s face.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt has created, as Ofsted put it, an imbalance of power in parents’ favour, a misplaced freedom of expression to criticise without consequence.

It means that parents now have a licence to behave more badly than the pupils. There is no sanction for so doing: no detention after school nor being made to write 500 lines on the blackboard; no being told that it’s your own time you’re wasting.

In a sense, it’s another example of parents “gaming” the system. This has happened for years in districts with mixed housing: aspirational families have moved from one area to another to place their children in the catchment area of the best available school. I did this myself, a couple of decades ago, at some considerable financial loss.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSome less scrupulous parents claim to have moved without actually having troubled an estate agent: putting a relative’s address instead of their own on the school selection form.

This kind of middle-class cheating, if cheating it be, was the subject of a BBC documentary this week, which made the not unreasonable point that every place at a desirable school occupied by a child from a “good” family came at the expense of an underprivileged boy or girl.

That’s an oversimplification, but there is no doubt that the class divide in our schools is as wide as it was in the days of the 11-plus, when our children’s education – and perhaps their future – hinged on a single exam result.

It shows no sign of narrowing. On the contrary, in a poll this week among current undergraduates – as liberal a group as you’ll find anywhere, outside Jo Swinson’s new office – fewer than half supported the idea of letting poorer people with lower grades than theirs into university.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere was, acknowledged the director of the think tank behind the findings, “considerable work to be done on winning over hearts and minds”.

But that is made more difficult if parents don’t set an example to their children on how to behave. Perhaps I’m on thin ice, having upped sticks all those years ago, but there is a world of difference between taking a life-changing decision in the hope of improving the prospects of one’s children, and dashing off an ill-considered tweet to a teacher on the way back from the pub.

It is a shame but not a surprise it has come to this. Many teachers, my son’s included, have actively shared their email addresses and encouraged a constructive, out-of-hours dialogue with their pupils – but there have to be limits, and social media should be placed squarely outside them.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt shouldn’t be hard to put right. It could be a quick win for Gavin Williamson, the new Education Secretary. Email addresses need not be publicly accessible; a presence on social media not made an expectation.

An open door is all very well – but let’s not mistake it for open season.