The legacy of David Oluwale and the power of the arts - Anthony Clavane

Degrees in the performing arts are routinely dismissed as self-indulgent, actors are constantly caricatured as luvvies and government adverts urge performers to retrain in other areas.

This dreadful virus has decimated the cultural sector – which, it should not be forgotten, is worth £32bn a year to the UK economy – with thousands of artists finding their livelihood put on hold by the pandemic, or even destroyed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis column has argued on several occasions that the arts are the life and soul of our nation. Some of our greatest cultural figures – from Shakespeare to Banksy – have been an outlet for creativity, inspiration and beauty.

But I was also reminded of the sector’s social and political importance when hearing the fantastic news that British-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare has been commissioned to create a sculpture in memory of David Oluwale.

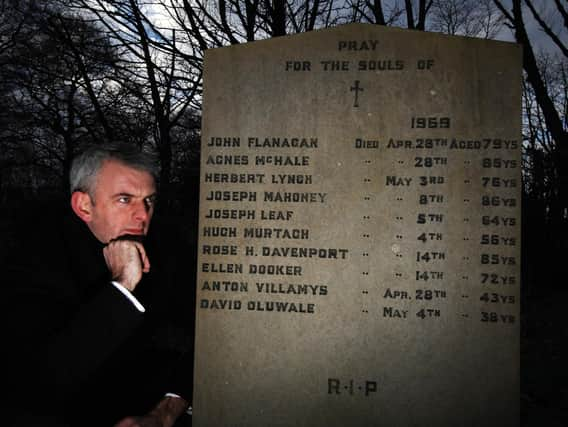

Again, I have mentioned Oluwale’s tragic story in a previous column. He came to Leeds from Nigeria in the 1960s with high hopes of becoming an engineer, but ended up drowning in the River Aire at the age of 38 after being harassed by West Yorkshire police officers.

Two policemen were found guilty of multiple assaults against Oluwale in a trial which highlighted the extent of racism in the city.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOver the years many campaigners, particularly the members of the David Oluwale Memorial Association, have advocated a memorial to Oluwale. They must be delighted that Shonibare’s sculpture, set to be unveiled in three years time, will be permanently installed in a new park planned for the city centre.

But they would be the first to acknowledge the role of the arts in raising awareness of the scandal.

First came the radio play Smiling David, written by Jeremy Sandford, not long after David’s body was discovered in May 1969.

Then came Time Come, a powerful 1979 poem by Jamaican dub poet Linton Kwesi Johnson. I first read about the tragedy in 2007 in a wonderful trilogy of stories by the novelist Caryl Phillips entitled Foreigners: Three English Lives, which meditates on the notion of arrival and departure by water.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNot long after came a wonderful social history, The Hounding of David Oluwale, which won the crime writer’s Golden Dagger award. It was written by Kester Aspden after police paperwork detailing the case had been declassified under the 30-year rule.

I remember going to the West Yorkshire (now Leeds) Playhouse in 2009 to see an excellent play by Oladipo Agboluaje, adapted from Aspden’s book.

And there have also been amazing poems by Jackie Kay, Zaffar Kunial and Ian Duhig – and an impressive collage For Oluwale, by the artist Rasheed Araeen, which was first shown at Swiss Cottage Library.

And now we can look forward to a brand new art work, the centrepiece of a visionary park being built on the site of the former Tetley brewery. It will be unveiled in 2023 to coincide with Leeds’ wider city of culture year.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdShonibare, who was nominated for the Turner prize in 2004, said the memorial would be a reminder of a dark chapter in the city’s history.

It would also, he added, “remind people that we live in a multicultural society and diversity is important. People are not actually asking for much: we’re asking for employment, and that you treat us equally. That’s all we’re asking for, I don’t think that’s too much to ask.”

Of course, critics will argue that artists, particularly public art institutions, should always strive to remain apolitical.

And many would agree with Ricky Gervais’ attacks on actors for raising political issues. “You’re in no position to lecture the public about anything,” the comedian

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Adscolded Hollywood stars. “You know nothing about the real world.”

But as the US political scientist Joseph Nye famously declared during the Cold War era, “soft power” can be wielded through the arts.

And, as the many artistic tributes to Oluwale have shown in the five decades since he was hounded to his death, they can hold up a mirror to society’s ills and, in the toughest of times, remind us of the injustices, inequalities and dark history of a city.