“A fifth emergency service”: the hidden key workers in Yorkshire’s libraries

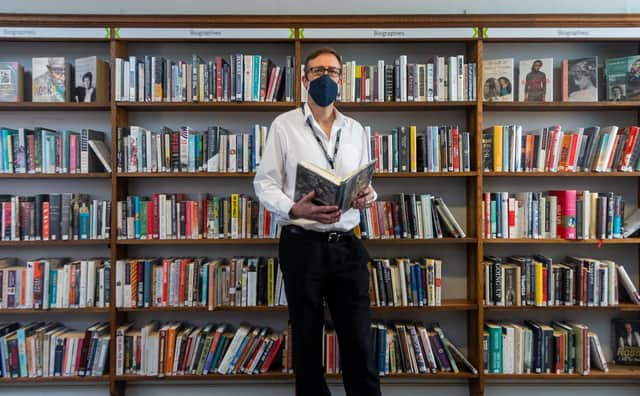

Throughout England’s second national lockdown, the Yorkshire libraries where Emily Cooke holds two part-time jobs were closed to the public.

The shutdown lasted for a month, and reopening was planned for the day restrictions ended, on December 2. As Emily prepped for work on December 1, however, an email landed in her inbox:

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We all got an email saying that they’re not reopening any libraries until January”, recalls Emily, who is speaking to The Yorkshire Post under a pseudonym as she does not want to put her job at risk by revealing her real name.

“It was a decision made by councillors...they ignored all the input from our senior management...we couldn’t believe it”.

Like many other decisions made by high-ranking officials throughout the pandemic, the resulting backlash forced a u-turn, and the libraries eventually reopened as planned. For Emily, however, the incident sums up the problem with how libraries like hers are currently governed:

“Nobody who makes decisions about us actually understands how a library works, or ever spends any time in libraries...in my area we’re blessed with senior management who get it, but they can only fight our corner so hard”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThough libraries remain as dedicated as ever to book lending, the blanket closure of UK libraries during the first lockdown in March highlighted more clearly than ever the library’s key role in other areas of public life - among these being internet access.

“For a lot of people the library is their only source of access to the internet”, explains Andrea Ellison, Chief Librarian for Leeds Libraries. Without it, people cannot apply for jobs or benefits nor check the news. They are, in other words, unable to participate in society.

“It became very apparent that [closure of libraries] cut off people’s access to computers”, adds Andrea. “It really excluded a lot of people”.

Her statement is echoed by Fiona Williams, Chief Executive of York Explore libraries, who adds that those without internet access at home likely “already have disadvantage in their lives”, and thus were hit doubly hard by library shutdowns.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA number of UK libraries, as a result, were deemed essential services and remained open on a limited basis during November’s month-long national lockdown. The decision speaks not only to the library’s indispensability in today’s society, but also to the expanding range of needs it now serves.

Emily, who has worked in libraries for over a decade, describes the library service as having unintentionally become “a one stop shop for people who need help”, akin to a “fifth emergency service”, with austerity squeezing or entirely decimating the availability of other public services in her area.

She points to a local example where the closure of a council customer services office led to a customer services desk being placed in the library as an alternative.

The desk in the library, however, was reduced from a five-day to a three-day service, with staffing cut from four to just one.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We get people coming in with quite desperate requirements - their electric has been cut off, they have no credit on their phone”, says Emily, pointing out that the absence of training budgets means that library staff simply aren’t able to help these people when the customer service employee is absent.

The problem is not so much with the presentation of these needs in the library, but the fact that libraries, too, have been decimated by a decade of austerity that’s left them ill-equipped to rise to the complex challenges they’re now presented with.

Across the UK, libraries have seen spending cut by over £250m (26.9 per cent) in the last decade, with around 800 closures nationwide between 2010 and 2019. In Leeds alone, more than a third of libraries closed in the five years leading up to 2016.

It’s an impact that’s been felt by almost every library up and down the country, including in Emily’s workplace, where she describes the long downturn as “insidious”:

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“At first you don’t really notice it, but as time goes on, you lose more staff, your equipment gets older, you have fewer books and people are less and less happy with the service…

“After five years you turn around and think ‘oh we used to have and do all these things that we don’t have access to any more”.

You’d be hard pressed to find a UK politician or councillor with anything negative to say about libraries, which are regularly lauded as a democratic force for good. Yet, says Emily, these praises rarely translate into sustained investment or support:

“Councillors love to talk about how much they support us but we’re last in the queue for building repairs and we’re last in the queue for funding”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe pandemic has further exacerbated these existing issues, says Emily, with the loss of in-person services elsewhere placing “extra pressure” on libraries as a point of contact for people struggling with issues ranging from housing to universal credit.

Though Fiona is keen to point out that York’s libraries have adapted to offer an array of virtual services throughout the pandemic, she concedes that limited access to the physical space has challenged the library’s role in bringing people together socially:

“[The library] is where you see people from all walks of life...it’s bringing the entire community together”.

In Leeds, this issue was tackled with a “Keep in Touch” programme which saw library staff call regular service users while the physical library was closed in an attempt to combat isolation.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhile praising such efforts, Emily fears that there may be no local libraries left to provide such services once the financial impact of the pandemic hits.

Even in a “best case scenario”, she predicts that all the small libraries in her area will be forced to close, adding that redundancies may also be a possibility further down the line.

The loss in local communities will be enormous, says Emily, given the library’s role today as one of few remaining public spaces where anyone can show up for free without being questioned or forced to explain their presence there.

While libraries can’t always help directly with a user’s life situation, says Emily, their presence in a community offers a safe space for people at any stage of their lives to come and read, sit, chat or use a computer with no caveats or questions asked.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“You’re not always changing someone’s life, but you’re there when they need you”, explains Emily. With small local libraries gone, not only will access to reading materials and computers become “more exclusive”, she says, but the ability for people to “reach out and have somebody reach back” will be gone.

The pandemic has already impacted the day-to-day jobs of library staff across the country. Under Covid-secure restrictions, computer use is being limited across the country to pre-booked time slots of one hour or less, forcing staff to gate-keep access to people who are often using computers to fill out benefits applications or write CVs.

“We’re not supposed to offer extra time for any reason, even if someone’s doing a job application...we all feel it’s incredibly unfair”, says Emily.

“It’s going to put off a lot of vulnerable people from engaging with us - many have anxiety, many feel like if they ask for help they’ll get into trouble”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn spite of these issues, Andrea feels relatively positive about the future for Leeds libraries, saying that the pandemic has “taken [Leeds libraries] on a journey quicker than we might otherwise have travelled” with regards to the range of digital tools and resources available to library users.

It’s her hope that the pandemic will present a chance to “renew” and “refresh” the services on offer, which include a successful programme for aiding new local businesses.

Emily, however, maintains a bleaker outlook for the future, saying that serious change will be needed if libraries are not only to survive, but to cater to the needs of local communities:

“[Those in power] can’t just say they support us as a concept; they have to support us in reality, and that means being willing to spend money on us”.

“We need buildings that are fit for purpose. We need equipment that is fit for purpose. We need staff who are properly trained”.