From remote Himalayas to Nobel Prize Nominee, meet the Leeds academic who is one of the world's leading experts on human rights

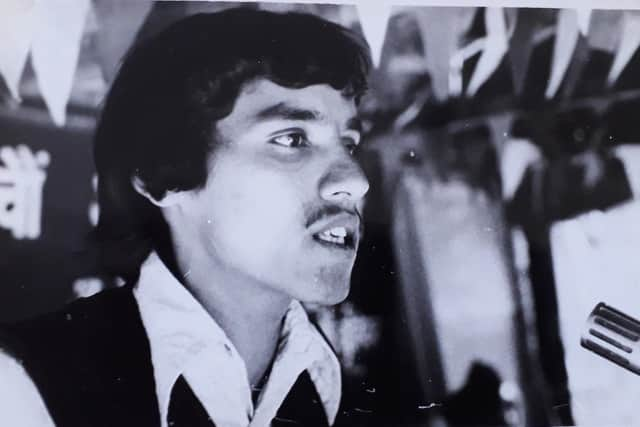

IT has been a lifetime’s journey from the remote foothills of the Himalayas to international pre-eminence as an authority on human rights for Surya Subedi. Along the way, he has been imprisoned for championing democracy, helped to rebuild a country torn apart by mass murder, advised the Foreign Office on promoting freedom and been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize.

He has seen and done enough to fill several lifetimes, but for the Professor of International Law at the University of Leeds and QC who has appeared in international courts, there is still much more to do in fighting to improve human rights across the world.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNow Prof Subedi, 64, has told his extraordinary story in a new book, The Workings of Human Rights, Law and Justice: A Journey from Nepal to Nobel Nominee. It is filled with insights into his work with the United Nations and governments around the world.

Prof Subedi says: “I wanted to explain to the wider public what it means to negotiate human rights with governments which have committed to embarking on the route to democracy, the rule of law and stronger human rights and how I, as a human rights expert and a United Nations rapporteur, can assist countries in the process of democratisation.

“My own experience in fighting for democracy in my native country when I was young, as a student leader, and serving a short time in prison and then advising the King of Nepal were very useful in writing the book.”

His journey began in an isolated region of Nepal, where his father, a teacher, established several schools. It was so remote that when the 15-year-old Surya won a place at the country’s only university, it meant a two-day trek just to catch the bus to the capital, Kathmandu. He became leader of the students’ union, and began campaigning for greater democracy.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I have always been passionate about fairness in life. At that time Nepal was ruled by an absolute monarch and political rights were limited, therefore I became active, writing about it and giving speeches, and the authorities thought I should be detained because I was going too far in opposing the government. My intention was to make the system more democratic, but they feared my campaign could lead to the overthrow of the government, which is the reason they detained me.”

It was to be a terrible three months in prison –stiflingly hot, and without enough food or water, conditions which Prof Subedi believes caused him long-term kidney damage. “It was a dreadful experience. Worse than going to prison, I did not know when I would be released. One could be detained for a long time, so I was worried about not being able to complete my degree. At that time, many political activists were detained for two, three, four years without trial, and that was my worry.

“I was kept for the first two weeks in police custody, where the conditions were appalling. I was moved to prison where the conditions were slightly better and I was treated as a political prisoner. They were treated better than other prisoners convicted of breaking the law of other kinds.”

He was released as the King of Nepal bowed to growing public pressure for change, and Dr Subedi would go on to advise the monarch as the country became more democratic. Prison convinced him to devote his life to human rights, and he won a British Council scholarship to come to the UK in 1986, where he studied at the University of Hull and then the University of Oxford.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe became a professor of law at Hull before moving to Leeds, writing extensively about human rights and the plight of countries living under dictatorships or emergency rule after military coups.

Prof Subedi was awarded the OBE in 2004 for his services to international law, and from 2010 to 2015 acted as an adviser to the then Foreign Secretary, William Hague. In 2009, he was appointed by the United Nations as its special rapporteur for human rights in Cambodia, which had a turbulent history including the Khmer Rouge regime of the 1970s which murdered hundreds of thousands of people and, more recently, an abysmal record of poverty and government corruption.

Prof Subedi says: “They had a horrendous past and I said, ‘Look, I’m here to assist you to accelerate the process of democratisation and reform the national institutions responsible for opposing human rights’. I began looking at the manner in which the courts operated, whether the judiciary were independent.

“In Cambodia the same political party had been elected again and again, and people were losing confidence in the political system. I left my Cambodian mandate on a positive note. They accepted my key recommendations and the country is a better state now. Seeing these things on paper is one thing, but implementing them in practice is quite another.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe practicalities of doing that are at the heart of his book, and Prof Subedi believes that engagement is essential to making progress. “The main lesson I have learned is the contribution an individual can make to the enjoyment of human rights by other people. My approach has been that it is better to make a small difference rather than no difference. That’s number one.

“Number two, is rather than scoring a point, engage in dialogue with the people who can bring about a change. Rather than naming and shaming, it is about encouraging them to do more, and educating them and assisting them.

"Those who are in power, especially in developing countries, are surrounded by people telling them that what they are doing is great, but what they are not benefiting from are critical constructives from other people. Those in public office should be prepared to listen to criticism so they can perform better and improve the systems in the country.”

His expertise in international law and human rights means that the plight of Ukraine – and the atrocities committed against its people by Russian forces – are at the forefront of Prof Subedi’s thoughts. He believes that reform of the United Nations and the way the international community is structured is essential if Vladimir Putin is to be held to account for war crimes.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We need to learn the lessons from Ukraine and other crises around the world and revisit the framework and political architecture that was put in place after the Second World War, but is outdated now. Many of the mechanisms under the United Nations system have not been terribly effective, and we need to devise a new system whereby the international community can operate more effectively.”

In particular, Prof Subedi believes the power of veto in the UN Security Council is an obstacle to decisive action – but he has faith in the ability of international law to deliver justice.

“If the United Nations system is willing to hold those responsible to account, and is effective, the long arm of the law should eventually reach those people who are involved in committing these atrocities.”

The Workings of Human Rights, Law and Justice: A Journey from Nepal to Nobel Nominee is published by Routledge on April 22.