What Giles Duley learnt about love, hope and war after losing three limbs in Afghanistan

“The focus is always on the day I stepped on the IED but in many ways the struggles were after that,” explains Giles Duley, a photographer who lost both his legs and his left arm in 2011 as a result of a landmine in Afghanistan while out on an assignment with the US military.

Duley was conscious throughout as US medics airlifted him from the scene in a helicopter and saved his life in the immediate aftermath of the improvised explosive device going off, but his fight for survival was only just beginning.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDuley, who is coming to Yorkshire this week to discuss his extraordinary life story as part of a new series of public lectures called Think Leeds, says gradually coming to terms with his new reality after being flown back to the UK for specialist hospital treatment produced some very dark days.

“The 46 days I spent in intensive care were brutal – you are fighting for your life. On two occasions, my family was called in to say their final goodbyes. That was deeply traumatic. But you are constantly being monitored, jabbed, having your bloods taken and the lights are never off so there wasn’t much time to think.

“The real struggle was when I was moved to the High Dependency Unit and I could start to think about things. When you have to come to terms with the reality of having no legs and one arm and that you might not walk again, you think ‘I won’t be able to do this’. I spent pretty much a year in hospital and had 37 operations. I was thinking, ‘I don’t know if I want this life’. I felt my life was over.

“I remember thinking I wish I had just died on the helicopter, it would have been easier for everyone. About three months after I got injured was the first time I had been out of bed. I saw myself in a mirror for the first time and was shocked by that. Everything came crashing home that day. I just thought I don’t want to be this person.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“But by the next morning my stubbornness had kicked back in. I thought, you can’t change any of this – you can sit here crying but this is your life now. I decided from then on to only focus on the things I could still do. Obviously I am going to have restrictions but in a very simplistic way I thought to myself, if I can still take photographs nothing else would matter.

“The first time I took a photograph again was behind the scenes at the Paralympics in London. It was the perfect job and that boosted my confidence.

“At the beginning there was a lot of people trying to create devices to help my take pictures, devices for my missing arm. Although I was grateful, actually I found them quite cumbersome. I made the decision I would have nothing. I have the same camera I have had for 25 years, I do it one-handed and don’t even think about it any more.”

But as well as his injuries physically changing the way he took photographs, it also changed his emotional engagement with his subjects.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn a cruel irony, the assignment in Afghanistan were he was injured had been due to document the impact of IEDs on ordinary civilians and children, with Duley scheduled to spend time at a hospital after his time with the US military. He made an emotional return to Afghanistan in 2012 to complete the second part of his trip.

It became the subject of a Channel 4 documentary called Walking Wounded: Return to the Frontline and his talk in Leeds this week will be introduced by Siobhan Sinnerton, the woman who directed the film.

Duley says it was a sobering experience. “People who had been injured in very similar ways to myself were receiving support that was nothing compared to what I received. Seeing them rebuilding their lives made me think I really can’t complain about anything and I am one of the luckiest people in the world.”

Even before the life-changing injuries he suffered in Afghanistan, the London-born Duley, who is now 48, had lived an extraordinary life.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAfter being left a camera and a book by renowned war photographer Don McCullin by his late godfather when he was a teenager, Duley developed an interest in photography.

“It is funny how people say you are lucky to find what you love in life. But I didn’t find photography, it found me by accident. I had always struggled at school and when I got given the camera it was like I was given my voice. I could communicate with the world by taking photographs.”

He enrolled at Arts University Bournemouth but quickly dropped out after becoming disenchanted by the amount of essays he was expected to write when he instead wanted to focus on taking pictures. But he quickly worked his way into music photography and began what he smilingly calls his “rock and roll years” in the 1990s.

He got his big break when he was just 19 after being commissioned to follow US rock band The Black Crowes on tour in America.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“On the tour bus, the bass player was drinking from a bottle of Jack Daniels and asked if I would like to have some. I said yes and he got out a whole fresh bottle and passed it to me. It was like everything I had seen in films and books. When you are a photographer, people let you into their lives for a moment. It was a really exciting time.”

Duley was soon photographing the likes of Blur, Oasis and The Prodigy at the height of Britpop and his portrait of American singer Marilyn Manson was voted by Q Magazine as one of the “Greatest Rock Photographs Of All Time”.

But despite his external success, Duley says he was growing increasingly unhappy with the jobs he was being asked to do involving Big Brother contestants and partially-dressed female celebrities

“It felt really vacuous and meaningless. A relationship with a camera is like a love story and suddenly it was not working anymore. On the outside, I was enjoying amazing success but I wasn’t happy.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe says he finally reached breaking point when he was commissioned to photograph an up-and-coming actress in a London hotel.

“There was an argument between her and her agency about her state of undress and whether she would be topless and she was in tears. I thought, ‘God this is horrible and I don’t want to be part of this’. The rock and roll story is I threw my camera out of the window but I actually threw it on the bed and it bounced out of the window.”

Duley moved out of London and got a job in a bar in Hastings.

“I was only 28 or 29 and thought my life was over in many ways. I was very lost. I was in a very deep depression and drinking too much.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut a chance meeting in the pub at work set his life in a completely different direction and restored his love of photography.

Duley met the parents of a young man with severe autism called Nick who said their son was interested in music, leading Duley to explain his own background in the industry.

“They thought it would be good for him to spend time with someone interested in music. I started doing that and before I knew it I became his full-time carer.”

It also saw him pick up his camera again to document Nick’s life and difficulties. Duley says a picture he took of Nick’s injuries after he had been self-harming resulted in him receiving improved support from social services.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“That was when I realised I could use my skills to have a positive impact on other people’s lives. That was a gamechanger for me.

“It meant social services were really confronted by his reality - it really shocked them but they really saw what was going on. That was when I saw the power of photography. Nick comes to every exhibition that I have and I owe him.”

The experience reignited Duley’s love of photography and he decided to restart his career - this time by using his camera to document the lesser-known stories of human suffering and resilience.

“I remembered how it felt when I was 18 and I had Don McCullin’s book. I realised my heart had always been in doing stuff around conflicts.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“In many ways my life had fallen apart. I was living above a pub, single and with no real career prospects. I remember saying I just want a second chance at life and realising nobody else would give me that chance, I would have to do it for myself.”

He made contact with various charities to arrange to photograph their work in countries such as Angola, South Sudan and Bangladesh.

He says when he looks back on his photographs from his first trip to Angola, he feels that while they were technically impressive they did not get to the heart of the subject in the way he does now.

“I was photographing these people and I didn’t know what their stories were. I had a distance between myself and the subject.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDuley says that the terrible injuries he suffered in Afghanistan have ironically gone on to open many doors for him in his career. He has become a popular international speaker and travelled to 19 countries last year alone on photographic assignments.

In one of his first talks in 2012 after his injuries, Duley reflected on how he had “become the story” as “my body was the living example of what war does to somebody”.

He reflects today: “War is often a very remote thing for people and I was the ‘living photograph’, I was an image people could see and connect with. People will stop and listen to me about the impact of war. I don’t think I realised the power of telling stories until started doing these talks. I’m grateful that opportunity came about because of what happened. I now take a photograph and tell the story around it. It changed the way I work completely. I discovered I love telling stories and I love doing talks.”

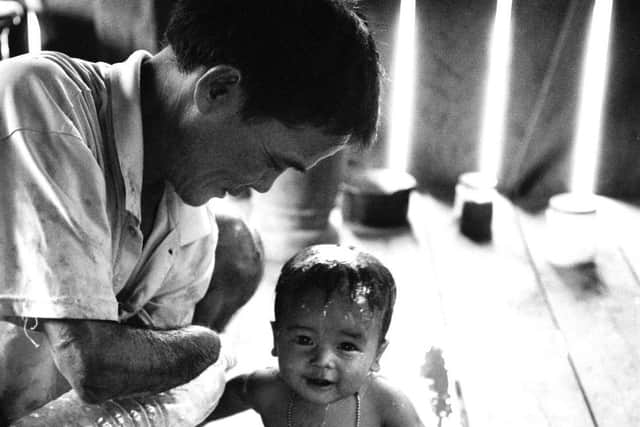

He says his injuries also allowed him to better connect with some of the subjects of his photography, who had been through terrible experiences themselves.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“There is always an element of photographing someone going through the worst moment of their life and the discomfort that comes with that. After I got injured it just started a conversation with some people.”

In October 2015, Duley was commissioned by the UN Refugee Agency to document the unfolding refugee crisis in Europe.

He spent seven months on the project but says he was shocked by the response he received to it from some quarters.

“I was telling the stories I had been telling for years but suddenly it was on the shores of Greece, in Germany and in the Balkans. I never thought I would photograph these stories coming to Europe.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Suddenly it became a political thing, I was receiving hate mail saying my images were fake news. That was quite hard. People didn’t want to believe the truth of these stories.”

The project resulted in a book he called I Can Only Tell You What My Eyes See – a title that was a direct rebuke to those questioning the veracity of the powerful images he had taken.

“When somebody asks who do you work for, I say for the person in the photograph. My concern is that person and their story. The most important thing for me is to do justice to them.

“A photograph can change a life and it doesn’t even have to be of the people in the image. I remember being contacted by a guy from Australia who was at medical school who said he had wanted to become a doctor after seeing my photograph of an injured child in Afghanistan.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“As a photographer you can’t change the world but I hope I can influence the people that can.”

Duley says despite what he has been through personally and documenting many bleak and desperate situations, his work has given him a positive outlook on life.

“I’m always trying to tell people there are terrible things going on in lots of places but there are amazing people in these countries. I go to places where people have lost their homes and loved ones to war and I can see hope and positivity from them and I want to bring that message back here.

“I don’t call myself a war photographer; I document love and relationships.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I believe if somebody was walking past a burning house and saw somebody in distress, they wouldn’t ask if they are gay, straight, black, white, Muslim or Christian, they would go and help. It is my job that people see somebody fleeing a war in the same way they would that burning house – just somebody that needs support.”

Talk part of new lecture series

Giles Duley’s talk Love, Hope & War is the first Think Leeds talks, a new series of lectures aimed at the screen-industry community.

Organiser Ali Hobbs says: “I wanted to put on a series of talks in Leeds that really connect creatively with the growth of our city. “It’s such an exciting time for Leeds and the wider region. These talks will focus on technology, photography, the arts, film, broadcast media and

journalism; incredible people doing exceptional things.

“I want Think Leeds events to inspire and excite our community.”

Giles Duley’s talk Love, Hope & War will take place at Left Bank Leeds on Thursday, March 12, at 6.30pm. Click here to book tickets.

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.