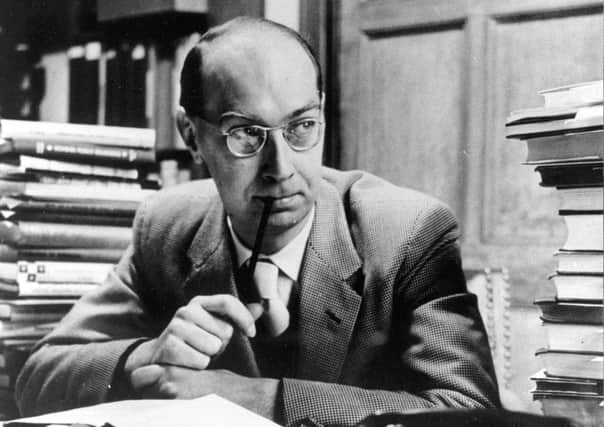

Philip Larkin's final archive reveals chapter and verse on a poet and his parents

“They **** you up, your mum and dad”, he wrote in 1971, in his poem, This Be The Verse.

“They fill you with the faults they had | And add some extra, just for you,” Larkin added.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut nearly half a century on, newly seen letters from his last major archive to have remained unpublished, suggest that Hull’s most famous bard got on famously with his mother and father – and that it was his older sister, Kitty, with whom the relationship was fractured.

Larkin’s contradictory private life, away from Hull University’s Brynmoor Jones Library, where he worked for 30 years, has fascinated and divided critics since his death, at 63, in 1985.

An exhibition mounted last year as part of Hull’s tenure as UK City of Culture, revealed bookcases full of pulp fiction, rude drawings and a top shelf stashed with pornography.

Yet the new letters, edited into 688 pages of highlights from 41 years of writing home, reveal an altogether more placid side to his personality.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe correspondence shows an “empathetic and positive relationship” between poet and parents, said James Booth, editor of Philip Larkin: Letters Home 1936-1977 , to be published next month.

But despite the meticulously kept paperwork, no trace remains of Sydney and Eva Larkin’s correspondence with their daughter. There is only a sparse surviving fragment of correspondence between brother and sister, which, said Mr Booth’s publisher, Faber, gives “an enigmatic glimpse of a complex and intimate relationship”.

Mr Booth said Sydney had given Kitty an “inferiority complex” and that Philip Larkin thought he had “bullied Kitty into internalising his low estimation of her”.

Some 10 years the poet’s senior, Catherine Larkin, known as Kitty, was thought not to be close to her sibling, although he respected her opinion, and sent her copies of poems he had published while at Oxford, to solicit her views.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLarkin’s literary executor and friend, Anthony Thwaite, said it was “very difficult to reconcile” the published Larkin with what he called the “extraordinary” collection of letters home.

“I had always imagined he was rather squashed and frightened, a combination of fright and boredom,” Mr Thwaite said.

“But in fact what comes through the letters is an extraordinarily cheeky affection.”

In the letters, Sydney Larkin, who was city treasurer in Coventry, is described as a “conservative anarchist” who admired Hitler. It had been known that Larkin senior attended two Nuremberg rallies in the mid-1930s.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe emerges as the dominant figure to his timid, depressive wife, who died only eight years before her son.

In her last years, following three decades of widowhood, she was diagnosed with dementia, and was cared for by her children. The the letters paint a touching portrait of the poet’s affection for her.

Several of his verses from the time are dedicated to her, and the mood of despondency that characterises his later verse appears to have been coloured by her condition.

But the correspondence also reveals a frivolous side to Larkin, in the large number of drawings he doodled across his letters, depicting himself and his mother as “Young Creature and Old Creature”.