How the Suez crisis sank the British empire

By 1956 the brooding sense of change was palpable.

More than a decade had passed since the end of the Second World War but the fervent hope for a more peaceful and fairer world hadn’t materialised.

Instead, people were waking up to an altogether different reality and a new “Cold” War but one still defined by opposing ideologies - this time capitalism and communism.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA fractured Europe was coming to terms with these new fault lines - Britain and France were reluctant to let go of their empires, while an “Iron Curtain” had dropped across Eastern Europe which had effectively become a series of satellite states controlled by Moscow.

But beyond Europe’s redrawn boundaries the world was changing, too, and for Britain the Middle East and in particular Suez became the staging post for proved to be its biggest foreign policy disaster of the late 20th Century.

Britain’s involvement with the Suez canal, which provided an important sea route to its empire, began in the 1870s when Benjamin Disraeli bought Egypt’s shareholding in the canal for £4m.

It was an astute investment and grew in significance following the development of the Persian Gulf oilfields in the first half of the 20th Century.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Suez crisis unfolded in July 1956 when Egypt’s President Nasser nationalised the canal, which at the time was run by a company jointly owned by Britain and France.

The two countries saw it as an attack on their status and wanted to overthrow Nasser. A secret plan was hatched that involved the Israelis pretending to invade Egypt, which was then used as a pretext to intervene.

Nasser’s populist move shocked and worried Britain and France who, in collusion with Israel, attempted to re-occupy the Canal Zone and overthrow the Egyptian leader who they viewed as a troublesome dictator.

The Israeli attack on Egypt began on October 29 and Britain and France, despite calling for both sides to stop fighting, used it as an excuse to send in their own troops against the inferior Egyptian forces.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlthough it was a shortlived military success it quickly became a political disaster with the UN and the United States demanding a ceasefire. US President Dwight Eisenhower was incensed and world opinion was firmly on the side of the Egyptians.

When the Soviet union threatened to intervene Britain, France and Israel were forced to withdraw their troops from Egypt in a humiliating climb down.

Simon Hall, Professor of Modern History at the University of Leeds, says the Suez Crisis was a major watershed in British history. “The old political deference towards the Establishment was disappearing and it [the Suez Crisis] symbolised a broader cultural and generational moment. It showed that old Etonians didn’t know best - something that has resonance today.

“It was important internationally because it didn’t so much destroy Britain’s status as a global power but exposed its decline which up until that point had been kept well hidden.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdProf Hall, author of 1956: The World In Revolt - says the Suez Crisis not only strained Britain’s relationship with the US, but showed we were no longer the power we had hitherto believed we still were. “Britain was forced to back down and this was humiliating because it was played out in front of the eyes of the world.”

It also brought forward the impending break-up of Britain’s empire, which politicians had long been aware was on the cards. “It was the beginning of the end of Britain’s empire and it boosted the growing anti-colonial movement. Much of our empire was gone within 10 years and this happened much quicker than people previously thought it would.”

But if Suez drew anger from political leaders around the world here in Britain it proved a hugely divisive issue, not dissimilar from the recent EU referendum.

“It split the country down the middle. It wasn’t a generational divide and it wasn’t a party political divide, but if you look at opinion polls at the time it really did divide opinion.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis spilled into confrontations between pro and anti-war demonstrators. “At Edinburgh University there were fist fights and in Manchester protests and counter protests saw fireworks being thrown. In Leeds, demonstrators led by students and members of Leeds University’s Arab Society marched from the university and down through the city centre.”

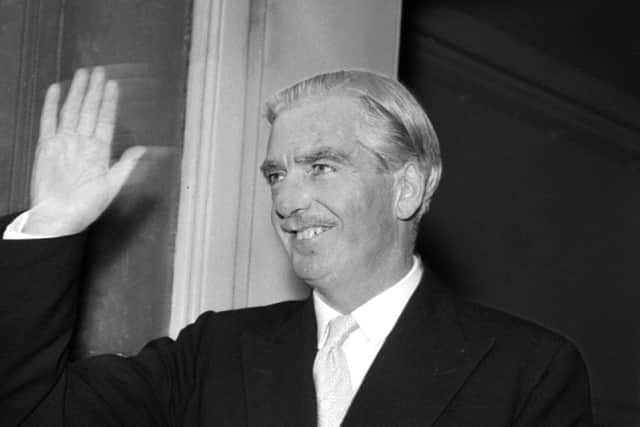

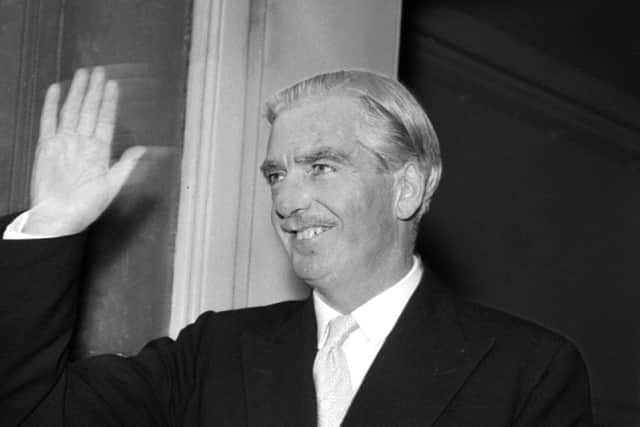

The Suez Crisis was more than just a loss of face for Prime Minister Anthony Eden and his Tory government, it represented something altogether more seismic.

John Osborne’s play Look Back in Anger premiered in London just weeks before the Suez crisis began to unfold and seemed to capture a change in the prevailing mood in Britain - a harbinger of what was to follow.

“The play was looked at in a new light. It was seen as an anti-establishment tirade and it paved the way for the satirists that followed in the early 60s,” says Prof Hall.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDr Adrian Bingham, a reader in modern history at the University of Sheffield, believes the Suez debacle raised deeper existential questions about Britain and its role in this brave, albeit uncertain, new world.

“Britain still defined itself through the Second World War and the mythology surrounding the idea of an island nation standing in defiance.

“People weren’t prepared to accept the nation’s decline even though the empire was already starting to recede with India gaining independence in 1947. There was still this feeling that we were a great power and Suez undermines that notion because it showed now there were only two superpowers - the United States and the Soviet Union.”

But Dr Bingham says Suez wasn’t just damaging to Britain’s prestige. “We had this view of ourselves as a great moral power, a force for good and a liberal nation. We were the mother of Parliament and stood up against the Nazis during the Second World War. But then we have this murky episode where we’re in collusion with the French and Israelis and Eden ends up lying in the House of Commons. So our stance as a moral power takes a big hit.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere are other repercussions, too. Britain and France viewed Nasser as a dictator and had hoped by acting firmly it would prevent similar uprisings occurring elsewhere.

“Britain’s reputation in that part of the world was exposed to criticism and it was difficult to recover from this because in the eyes of Egypt and other nations in the Middle East we were seen as hypocritical meddlers. Times had changed but we hadn’t.”

Suez shaped Britain’s outlook on the world for decades to come, as Prof Hall points out. “It meant we had to stick close to US foreign policy and this became an article of faith in Whitehall - we saw this played out during the last Iraq war.”

Ultimately the price of Suez was that Britain effectively became subservient to Washington. The relationship between Britain and the US was rebuilt, reaching its zenith during the Reagan and Thatcher years, but we were now undeniably the junior partner. “Britain was very much in the back seat,” says Dr Hall.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSuez didn’t spell the end of Britain’s reign as a global superpower, but it did signal the beginning of the end.

1956 - a year of global revolt

In 1956 the demand for civil rights for African Americans provoked conflict, rioting and lynching; there was the bus boycott associated with Rosa Parks in Montgomery, Alabama, while proposals for the end of segregation in schools revived the dispute between the respective rights of States and the Federal Government.

In South Africa the apartheid government arrested more than 50 opposition leaders, among them Nelson Mandela, and charged them with treason.

France was engaged in what became the most vicious of wars in Algeria, and then came anti-Soviet uprisings in Poland and Hungary.

In retrospect, this was the year in which the dissolution of the French and British empires became inevitable - Ghana achieved independence and the first cracks appeared in the Soviet Empire.