The ‘nightmare’ Yorkshire visit which made David Cameron realise that Britain would back Brexit

“My worst nightmares”. David Cameron already knew that the EU referendum result was hanging in the balance when he toured Yorkshire exactly two weeks before polling day.

He visited The Yorkshire Post, his tie already ripped off, for a no-holds barred Q&A with this newspaper’s readers where he denied – naively with hindsight – that his emphatic support for Remain was, in fact, energising his Brexit-backing opponents.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTom Richmond: Whatever happens, Cameron will be the big loser in EU referendum“Oh, the British people are not so stupid as to prioritise their opinion of me ahead of all of the benefits that come with being part of the European Union,” he ventured in the lift as he left.

Yet, within hours, the then Prime Minister was changing his view. From this newspaper’s offices, he travelled to the BBC’s studios in Leeds where he watched, from “a voter’s perspective”, a “five minute package on Slovakian travellers in Rotherham”.

Tom Richmond: After such a naive Brexit campaign, David Cameron had to resign“Local people were saying ‘I’m moving out. These people are taking over our parks and public spaces and the place is a complete mess’ and, crucially, ‘We never voted for this, it’s not fair’,” he writes in his just-published memoir For The Record.

“Their comments were understandable. That was the moment I realised our argument about the economy was quite complicated, while Leave’s argument about immigration was very simple. I thought my worst nightmares could come true. I thought, we could lose this thing.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTom Richmond: The EU referendum lessons David Cameron can learn from Harold WilsonIt did not end here. Shortly afterwards Boris Johnson and Michael Gove – once-fond friends who had become fierce foes – sent Cameron a letter criticising “the tens-of-thousands immigration pledge”. Johnson went further by accusing unnamed politicians of breaking promises.

“It wasn’t any old pledge; it was part of the manifesto they had just been elected on. The rules of engagement had been abandoned. This was open warfare,” concluded the then Tory leader who, by then, was in the fight of his political life.

Tom Richmond: Reputation of David Cameron is sunk by floods and political ‘spin’And worse was to come. A week later, Batley & Spen MP Jo Cox was murdered by a far-right terrorist and the referendum campaign was suspended as Cameron travelled with senior Parliamentarians to Birstall to pay their respects.

Reading his 732-page book, he is clearly tortured – and tormented – by the murder of an opponent whose humanity had touched so many. “Everything else, all the arguments and preoccupations of the past few weeks, suddenly seemed small, distant and irrelevant,” he now reflects. “A woman had lost her life – a husband with his wife, two children with their mother, two parents their daughter. Parliament had lost a politician with enormous promise. I felt sick. And I felt even sicker when it became apparent the referendum wasn’t irrelevant.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCertain that the “deranged actions of one individual” should not “stop democracy”, a brief period of national introspection and soul-searching overshadowed the difficult final week of the referendum in which Cameron admits his own culpability.

In promoting his book, a sombre-sounding Cameron has been remorseful about his own part in the political turmoil which persists to this day after the country defied his wishes on June 23, 2016, and voted to leave the European Union.

In doing so, he has revealed his own shortcomings – he was clearly unaware of the depth of the country’s ill-feeling; he was deluded if he thought the Leave campaigns would play by the rules and he was presumptuous if he thought he could use a handover period, after his resignation, to save his reputation.

For a Prime Minister steeped in public relations, Cameron also reveals his own inability to make a convincing case for EU membership. “After all, we had shifted very quickly from ‘big, bossy and interfering’ negativity to ‘stronger, safer and better-off positivity,” he concludes in reference to his botched re-negotiation in early 2016.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We were asking a lot of people to believe such a handbrake turn. And frankly, we hadn’t done enough to trumpet the achievements of the EU, such as ending outrageous mobile-data roaming charges, cheaper flights and reciprocal access to other countries’ healthcare systems.”

This week every Cameron interview has included a mea culpa along the lines of ‘I’m deeply sorry’. One of the country’s youngest ever premiers – he once likened himself to ‘the future’ – he has more to regret than most, if not all, of his post-war predecessors.

He also has longer to regret. He was not even 50 when he left 10 Downing Street just over a decade after he had defeated David Davis, the veteran Haltemprice and Howden MP, to become Tory leader.

Brimming with youthful optimism and exuberance back in December 2006, he noted how he “ended up with more people called David in the shadow cabinet (five) than women (four)”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“There simply wasn’t the range from which to choose. Come day seven I was at the Met hotel in Leeds unveiling a plan to elect more women and ethnic minority MPs (of whom we had, shamefully, just two),” he discloses.

Cameron was clearly taken aback by the criticism that he received over the creation of his A-List of candidates, but says he was vindicated by the election of 17 non-white and 68 women being elected as Conservatives in 2015. “It was worth the row,” he now concludes.

Cameron’s early ability to set the agenda – in contrast to Brexit – shines through in the passages about the formation of the coalition government in 2010 with Lib Dem leader Nick Clegg.

First Cameron consulted Tory grandees – included the aforementioned Davis – about his intentions. “The feedback was overwhelmingly that it would be right to reach out to the Lib Dems, although there was the odd exception. ‘Davis thinks it’s a bad idea’, I reported to my team,” he discloses. “Which means I’m probably on the right track.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCameron and Clegg then joined Gordon Brown, still the PM, in Whitehall on the Saturday after the 2010 election. Though this ceremony was ostensibly to mark the 65th anniversary of VE Day, coalition talks were underway – Clegg had stayed true to his word and opened talks with the Tories as the largest party.

Some veterans, says Cameron, even greeted him as ‘Prime Minister’, while a piqued Brown sought Clegg’s attention. “He’s still having a go at me,” the then Sheffield Hallam MP reported back to the Tory leader.

Cameron and Clegg then tried to slip the media. “As we sat down in a dingy room in Admiralty House, we’d discussed how we’d given the media the slip. Underground car park, I said. Switching cars outside the Home Office, he said,” writes Cameron.

“We went through our two manifestos, and talked about compromises. But the detail was for the negotiators. For us, it was about the bigger picture – and it was about trust. We agreed that we could and should work together. There was a mutual recognition that we could both be both be judged forever on whether we could make something unprecedented work at a time when our nation needed it most.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNot all shadow cabinet ministers agreed. Cameron names Chris Grayling and Theresa Villiers, the current Environment Secretary, as voices of dissent.

But Cameron – who once let slip that his favourite joke was ‘Nick Clegg’ – has no regrets about that Rose Garden press conference with his new deputy prime minister when they cemented their relationship.

“The banter and bonhomie did help to set the tone for what we were to embark on. They showed that Nick and I were confident that we could work together and were clear about our task: to confront the economic challenge ahead of us,” he says.

In contrast to those Ministers who communicate by text message or social media – Cameron laments the manner of Yorkshire peer Sayeeda Warsi’s resignation in one passage – the coalition worked, and lasted until 2015, because of its central core.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis was the regular ‘Quad’ meetings where Cameron and George Osborne, his Chancellor, met with Clegg and his confidante Danny Alexander, the Treasury chief secretary, to discuss differences and take key decisions. Two asides stand out. First, Cameron discloses the sense of isolation which Clegg felt because he had not got a “friend, confidant and partner” in government like the PM had with Osborne. “I could see what he meant. His senior Lib Dem colleagues only seemed his allies up to a point,” observed Cameron.

Second, Cameron claims that it was him – and not the “cautious” Lib Dems – who persuaded a “gung-ho Chancellor” not to cut the top rate of income tax from 50 to 40 per cent in the 2012 ‘omnishambles’ Budget. He says cutting the tax to 45 per cent still sent out a “pro-investment message”. He also defends the coalition’s approach to austerity and says that his many critics have not acknowledged the fall in “inequality and poverty” that took place.

Yet this working relationship explains Cameron’s genuine sadness when Clegg’s party was virtually wiped out in the 2015 election. “My triumph was my friend’s tragedy,” he wrote poignantly.

Cameron also respected Doncaster North MP Ed Miliband who led Labour in the 2015 election.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“He’d done what an opposition leader is meant to do: holding us to account, forcing us to move on policies,” he ventured before lauding Pontefract and Castleford MP Yvette Cooper as a “formidable intellect”.

Yet, throughout his premiership, Tory tensions on Europe dominated. In 2011 when MPs voted not to hold a referendum on EU membership, Cameron tells how Stuart Andrew, the new Pudsey MP, “came up to me and said that he backed my leadership, and knew he wouldn’t be there if it wasn’t for me, but because of the boundary review he would potentially be going for the same seat as anti-EU MP Philip Davies, and he had to rebel. I didn’t like it but I understood”.

Cameron also explains why he kept Chris Grayling in the Cabinet after the 2015 election. “He hadn’t excelled at justice, but getting rid of him would anger the right,” he said.

And while no reference is made to Grayling’s subsequent mismanagement of the North’s railways, this anecdote is telling because it reveals the extent to which David Cameron had been taken captive by his own party over Brexit – the one word which always define his life and times.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs Cameron said on the day of his resignation, the “greatest honour of his life” had been to serve as Prime Minister. But, as he now concludes, it was also his “worst nightmare”.

The ‘total panic’ over security at London Olympics

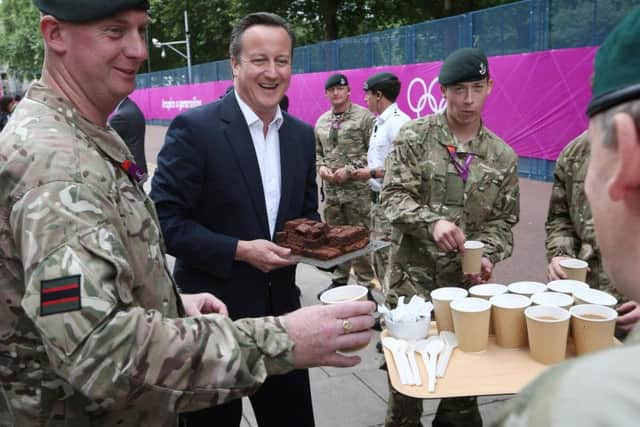

David Cameron describes witnessing the successes of Sheffield’s Dame Jessica Ennis-Hill, and Team GB, at the 2012 London Olympics as “a magic memory”.

However his book sheds light on the decision to put the Army in charge of security after contractor G4S could not provide sufficient personnel.

“Total panic,” he writes. “I had one of my bang-the-table, cut-the-nonsense moments. I insisted that 17,000 troops would be deployed overall.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I didn’t care what it would cost or how ‘sending in the Army’ looked. Security was non-negotiable. As ever, our service personnel were amazing, and the public loved their presence, which added to the patriotic atmosphere.”