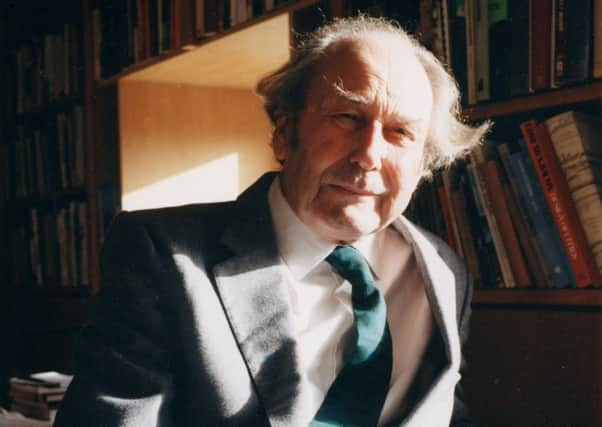

Professor Ivor Smith, architect

Often derided as one of Yorkshire’s ugliest buildings, the flats were the most spectacular example of the concrete jungles created to provide mass housing for those displaced by the wholesale slum clearance programmes of the time.

But what had seemed like an effective solution had become by the 1980s a byword for social decay, drug use and family breakdown.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPark Hill was by no means the only manifestation of such development in Yorkshire; Leeds and Hull also had blocks in the sky. But the scale of the Sheffield construction was awesome – 985 flats arranged into four “street decks” wide enough for milk floats.

They are standing still, Grade II* listed and the object of a colossal regeneration programme by the developer, Urban Splash.

They had been put up by Ivor Smith and Jack Lynn under the auspices of Lewis Womersley, chief architect of Sheffield’s housing committee.

It was after 1953, when Prof Smith took up a position in the city architects office in Sheffield, that he and Lynn drafted the first plans for Park Hill. They drew inspiration in part from Le Corbusier, the Swiss-French pioneer of modern architecture, and set out to create elevated streets that would replicate those of the neighbourhoods that had been bulldozed in their wake.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIvor Smith grew up in Leigh-on-Sea in Essex. His parents were from Yorkshire – his father a maths teacher and deputy Head, his mother a shy, conventional woman who also trained to teach.

At 13, his school was evacuated to Belper in Derbyshire, and he spoke fondly about his time there, cycling around villages drawing churches and industrial buildings, and studying Banister Fletcher’s History of Architecture. It was, he said, the time that laid the foundations of his career.

He left school at 16 and went to Southend School of Art, where he learnt to draw and paint, gaining a scholarship to The Bartlett, which was evacuated to Cambridge.

He was strongly influenced by Sir Albert Richardson, who took Ivor under his wing – teaching him that understanding and obeying classical principles was more important than exercising personal ego.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt remained his guiding light – his work not attempting to fashion sentimental facsimiles of the past but adhering to the underlying principles of space and place-making, interpreted in concrete, glass, steel and sometimes brick.

Ivor and his older brother Percy had been pacifists from their teens and were conscientious objectors during the war. When Ivor was called up during his time at The Bartlett, he was given the option of farming or mining, and chose farming. He worked in the Cotswolds, and later in Cambridge. Finally, he worked at a farm alongside a craft community founded by the controversial sculptor and typeface designer, Eric Gill.

When the war ended, he returned to his studies, and while at Cambridge met and married Audrey Lawrence. Their first child was born in 1948.

His time after Sheffield was spent in architectural practice and then in teaching. He became Professor of Architecture in Bristol, where he also opened a second architectural practice. Later, he was invited by the Commonwealth Institute to establish the first school of architecture in the Caribbean – where the syllabus was generated by the climate, culture and the local resources, rather than by copying schools of architecture elsewhere.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn his final years, he wrote Architecture an Inspiration, drawing together the key principles of his thinking, which he hoped would be accessible to students of architecture as well as a wider public interested in modern buildings. He also contributed to the Oral Histories project at the British Library.

Despite failing health, he remained active, and he and Audrey continued to go camping abroad well into his eighties, only stopping when he could no longer drive.

She survives him, along with four children, eight grandchildren – two of whom are also architects – and five great grandchildren.