Sister of mercy: My years at the coalface

She spent 14 years as its Sister, running the medical centre where she was responsible for the health and well-being of more than 2,000 men. The pit near Doncaster, in South Yorkshire, had been due to shut in the summer of 2016 but the move was brought forward unexpectedly with the loss of 430 jobs.

“I was devastated,” says Joan. “I really felt more could have been done to keep it going. There’s still a lot of coal under there and it’s just going to get filled in.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

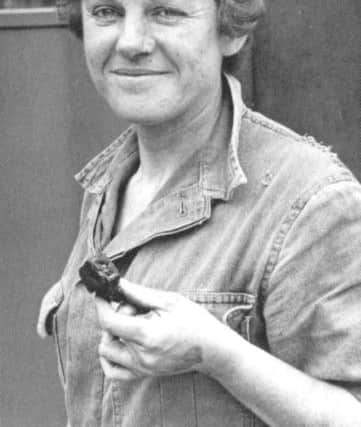

Hide AdThe 83-year-old former nurse has a close affinity with the colliery and it features heavily in her memoir, At the Coalface – The heartwarming story of a Yorkshire Pit Nurse.

The book has been co-written with Veronica Clark, a journalist and author, who she met at a creative writing workshop. Together they have produced a moving and uplifting story that offers a fascinating insight into the working life of a nurse in the second half of the 20th Century.

For Joan, it’s a story that began in Bentley, near Doncaster, in 1932. She was followed seven years later by her brother Tony, and then her younger sister, Ann. But when Joan was just 13 her mother walked out on the family, leaving her father, Harry, a deputy at Brodsworth pit, to bring up three children on his own.

“I learned how to cook and clean, so I could look after my sister and brother whilst dad went to work, so he could pay for a roof over our heads,” says Joan.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was while looking after her siblings that she decided she wanted to be a nurse and at the age of 16 gained a training place at Huddersfield Royal Infirmary.

This was 1948 and as well as caring for patients, young trainee nurses were expected to muck in with all the menial tasks. “The NHS was just getting started and you learned how to do all kinds of different things, you cooked, you cleaned and you did the laundry, things they don’t teach you now.”

After a couple of years at Huddersfield Joan moved to Hammersmith Hospital in London, where she continued her training and witnessed all kinds of pioneering techniques, including the successful separation of Siamese twins and one of the first kidney transplants.

While working in the capital she met her future husband Peter, and they married in 1954. Two years later they moved to Yorkshire and Joan took a job at Brodsworth pit. The colliery was building a new medical centre and needed a qualified nurse to run it. Joan’s father put her name forward and she got the job.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdShe found herself in charge of more than 3,000 miners who weren’t keen on taking advice from a female nurse. To make matters worse she was taking over from a man called Bert who the pit workers knew well and trusted. “What he didn’t know about first aid, wasn’t worth knowing,” she says.

Some of the men continued to go to him which made her job even harder. “I was 24 years old and working in a pit with 3,000 men who didn’t want a woman helping them, until they had an accident and saw me go down the pit and realised I wasn’t just a giggling girl and that I could do the job.”

Having cut her teeth at the pit she returned to London. Peter’s father died suddenly and he was called back to deal with family matters so they moved to the South.

Joan returned to Hammersmith where she became a Cancer Research nurse in charge of the hospital’s radiation unit. She later enjoyed a stint as a district and industrial nurse, working for BP, but when her husband developed heart problems they returned to Yorkshire.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn the summer of 1974, she took a job at Hatfield Colliery as the Sister in charge of the medical centre, which she ran along with three trusty medical room attendants.

Here she was responsible for the well-being of 2,000 men. It was a return to pit life, although now with 18 years’ experience as a nurse under her belt it was a less daunting prospect than when she worked at Brodsworth. “At Hatfield they’d already had a sister working with them so when I started it wasn’t much of a change.”

However, she knew she still had to earn their trust and acceptance. “I had to go to every part of the pit and I went down every fortnight so they got used to me,” she says.

She wasn’t afraid to get her hands dirty and the sight of “Sister Hart” dressed in a boiler suit, pit boots, hard hat, and headlamp, became a familiar one to the miners.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt didn’t matter how badly injured the men were, or how deep in the mine they were trapped, they knew she would reach them. But her skill and dedication were put to the test in November 1978, when she was first on the scene at the Bentley pit disaster, which claimed the lives of seven men and left 19 injured.

“At first I thought it was just a little incident with a Paddy train but then I was told that seven people were already dead,” she says. “It was terrible, I still get emotional when I talk about it. I can’t remember exactly what happened I just know that I didn’t stop from five in the morning until two-thirty in the afternoon, men just kept being brought in.”

Despite being thrown into this horrific situation Joan helped save numerous lives that day, carrying out amputations hundreds of feet underground in the pitch black.

Over the years she became a trusted figure amongst the pit workers, holding impromptu counselling sessions where they would discuss everything from health issues to any marriage problems they might be having.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJoan continued to care for the men during the Miners’ Strike of 1984-85. “I couldn’t actually go on strike because I was part of the management, so I had to go to work otherwise I’d lose my job. But I made sure that if any miners got hurt on the picket line they knew they could come to me.”

Although she couldn’t join them she organised toy collections so that the children of striking miners would have presents to open on Christmas Day. “Most of the men understood that I had to go to work and that I sympathised with them.”

After the strike she watched the miners trudge back to work and three years later she took voluntary redundancy. She feels strongly about the sad decline of the coal mining industry. “When a pit closes you don’t just lose that, you lose the galas and the camaraderie, there’s no village life, no community life, it’s all gone.”

Despite the heartache the pit closures caused Joan’s story is, ultimately, an uplifting one of a woman who helped blaze a trail for female nurses working in industry.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“People didn’t realise what we did. I think they thought we just sat in an office and put plasters on. But I always liked to keep busy and went to every nook and cranny of Hatfield. I threw on my overalls and boots and went underground to see the men, to talk them and to help wherever I could.”

Even now, more than 25 years after she last worked as a pit nurse, she still feels great warmth and affection for the miners she worked alongside. “When they see me they still call me ‘Sister Hart,’” she says. “It seems a long time ago now but I still feel very close to them. I loved my job and I loved the miners, they’re unique.”

• At the Coalface – The heartwarming story of a Yorkshire Pit Nurse, by Joan Hart with Veronica Clark, is published by Harper Element priced £7.99.