How public transport keeps billionaire Sir Cameron Mackintosh grounded despite musical Midas touch

Billionaire theatre impresario Sir Cameron Mackintosh uses public transport and even budget airlines. “Unless I need to be somewhere in a particular hurry, then I use very easyJet,” he laughs.

He means private jet – but he will go via the cheaper option if it’s possible. It’s a perfect metaphor for what Mackintosh does. He creates epic, extraordinary, record-breaking theatrical productions and when he needs to show the money on stage he does, but he’s ultimately in charge of the purse strings, so if he doesn’t need to spend the cash on a stage spectacular, he won’t. That, after all, is the job of a theatre producer.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMackintosh is the man who has defined musical theatre globally, from Britain, for over three decades. It’s not too much of a stretch to say that he has defined theatre itself for that long.

He has also helped Britain’s cultural industry, still one of our strongest exports, become what it is today. The billion he is personally worth is dwarfed by the billions his products generate for the cities lucky enough to receive a genuine Mackintosh.

It started when he was eight years old. “On my birthday I went to see Salad Days with my aunt at the theatre and I knew immediately that was what I wanted to do. I wanted to make what I had seen on stage,” he says. “I never wavered from that moment. I don’t think many eight-year-olds know what they want to do when they grow up, so I was very lucky.”

Speaking of growing up, it’s apparent that Mackintosh hasn’t. At 71 he has the verve and life force of someone way off bus-pass age, not of someone who passed it some years ago. “I told Boris that I wouldn’t still be here if it wasn’t for my senior rail pass. It makes travelling around London very easy,” he says. I take it to mean Johnson.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt’s weird that he uses public transport because he could afford to have himself helicoptered around the various theatres he owns (eight in London’s West End).

“When I travel by public transport it’s not some sort of inverse snobbery. I like to know the value of something like a train ticket so I know what it is like for someone to spend £75 for a theatre ticket and have to travel to the theatre. I don’t want to live in my own little bubble.”

More examples of how he does live in a bit of a bubble, like it or not, crop up in our conversation. Right now though, the credentials: although he has been defining theatre for three decades, he’s been making it for five – and not always so successfully.

Starting life as a stagehand, his first theatre production came in 1969. Anything Goes closed abruptly and £40,000 down. Home With the Dales and After Shave proved at least as disastrous.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe learnt from his mistakes and by the mid-1970s, he was producing shows that were, if not the mega-hits he would go on to create, at least not the disasters he started out making. Side by Side by Sondheim came in 1976, a first big success, and mention of it brings us to the first example of the Mackintosh Bubble. “I have to tell you both myself and Stephen Sondheim are the most inept dancers,” he says.

And the conversation moves on, like he didn’t just put in my head – and now I in yours – the image of knight of the realm Sir Cameron, dad dancing with the Oscar, Tony, Olivier, Pulitzer prize-winning composer Stephen Sondheim.

It’s a strange place, the world of Cameron Mackintosh. After starting to make a name for himself in the 1970s, the 1980s became a magical time for theatre made by Mackintosh. It began in 1981, when Andrew Lloyd Webber told Mackintosh about a musical he wanted to write, based on TS Eliot’s Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats. He played it for him on a piano in his flat later that afternoon.

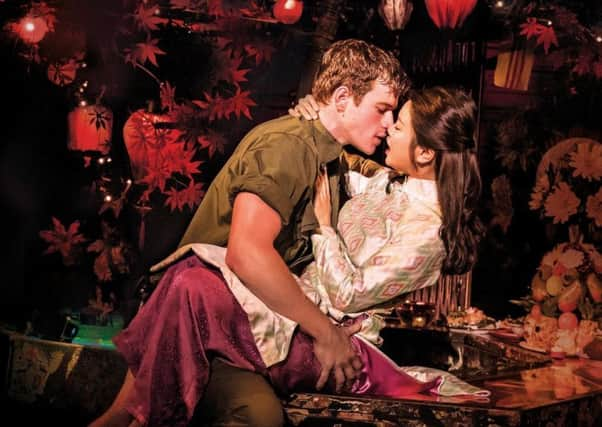

Mackintosh produced the show. It was called Cats. It went quite well. As did the next show Mackintosh produced in 1985, Les Miserables, and the one he produced in 1986, The Phantom of the Opera and the one he produced in 1989, Miss Saigon (the one we are talking about today).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe also produced on the West End stage Mary Poppins, Oliver! and last year Hamilton, which is currently redefining musical theatre for the first time since Mackintosh redefined it in the 1980s. “Of course after Cats, I wondered if it was a fluke,” he says. “Once I’d done it again, I thought, ‘well, you can’t keep just getting lucky.’”

So what is behind Mackintosh’s Midas Touch? “I can’t direct, but I can redirect. I can’t write music or sing, but I can interpret what a composer is getting at. I can hum a tune and a composer can write the music. I can’t dance, but I can spot if someone is out of time or step, I can’t write, but I am a very good amateur dramaturg and I am good at knowing what everybody’s jobs are. I’m also very good at smelling out a good idea.”

Perhaps that is one of the most remarkable things about Mackintosh’s reign at the pinnacle of his industry: the ideas he has turned into musicals sound utterly ridiculous. Cats singing about being cats? Fourth-longest running show on Broadway, box office receipts currently standing at £342.2m. Phantom of the Opera, a story about a deformed singer living beneath the Paris Opera House? Currently £5.6bn globally.

Then there’s Miss Saigon. The current UK tour arrived in Bradford last month and remains at the Alhambra until October 20, where it is earning nightly standing ovations. “It’s the last time I’ll do it in the UK,” says Mackintosh. “It is such a hugely complicated show. I’m currently touring it on both sides of the Atlantic, in fact I was in America yesterday getting it ready to open and I’m delighted it is doing so well at the minute because it does feel like a show that is very pertinent to today.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMiss Saigon transposes the plot of Madame Butterfly to Vietnam, with Vietnamese Kim falling pregnant with the baby of American soldier Chris, who leaves Vietnam and his new love and baby behind, only to return years later to discover his child. “The reason this musical is so popular is because of the truth at the heart of it, it is a real life, heart-rending story. It is also telling the story of humanity making the same mistakes over and over. When we see the boats full of migrants crossing the Mediterranean today, you realise that this story keeps happening. The musical could so easily be about Syria today. I love that people still come to see this show and that’s why we work so hard to give them an experience that is just the same as they would get if they saw this show in the West End, New York, or Bradford.”

Speaking of which, another trademark is Mackintosh’s shows are the same the world over. When he was first opening these mega-hits, how did he do it? “Concorde,” he says. “I owe at least half my career to it, without it, trying to get around the world for my shows would have killed me.”

The extraordinary world of Cameron Mackintosh.

Mackintosh Musicals:

Cats: opened in London’s West End in 1981, Broadway 1982. It is the fourth-longest-running show in Broadway history. Translated into more than 20 languages, it has grossed £342.2m.

Les Miserables: opened in 1985, is the longest running musical in the West End, the second longest in the world. Box office takings: £5.5bn.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMiss Saigon: opened in London in 1989, Broadway in 1991. The current tour at the Bradford Alhambra opened at Leicester’s Curve Theatre in 2017. Prior to the opening of the 2014 London revival the musical set a record for opening day tickets sales with sales in excess of £4m.

Miss Saigon is at Bradford Alhambra, to October 20. For tickets contact 01274 432000.