A century after the Battle of Jutland, maths make the sea give up its secrets

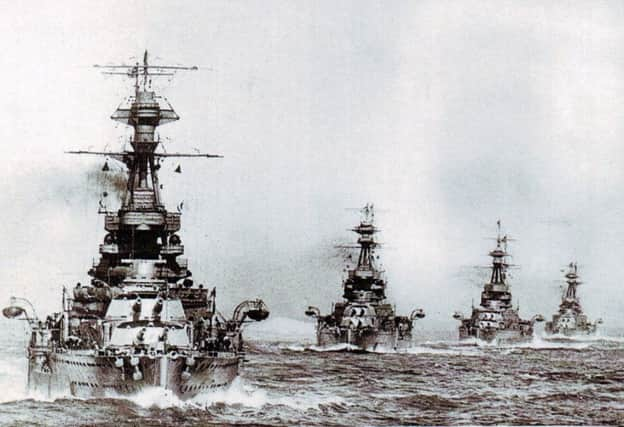

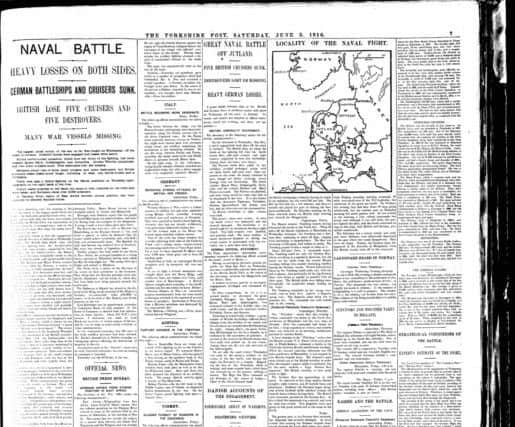

More than 8,000 men died in just 36 hours when the Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet, based at Scapa Flow on Orkney, clashed with the German High Seas Fleet off the coast of Denmark, during World War One.

14 British ships and 11 German vessels were lost, yet both sides called the Battle of Jutland a victory. The Admiral of the Fleet, Lord Jellicoe, has been criticised by many historians for being over-cautious, even though Britain remained the dominant naval force for the rest of the war.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut a group of Yorkshire mathematicians claims to have shed new light on the conflict.

Days before Jutland’s centenary, which has seen a commemorative display of thousands of ceramic poppies installed on Orkney, the researchers say “new mathematical insights” of the commanders’ behaviour reveal that Jellicoe’s decisions were in the best interests of the British fleet.

Dr Jamie Wood, from York University, said the figures proved that although the British lost more ships and more men in the battle, they retained “absolute superiority” in terms of numbers and big guns.

He added: “Numbers really, really matter and the British realised this. Before the British went for quality, they just built lots and lots of ships with lots of guns.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdColleague Prof Niall Mackay said: “What the German fleet hoped for was to lure out, isolate and destroy part of the British fleet and tip the overall naval balance in their favour. They would then have a chance to defeat the Grand Fleet and possibly win the war.

“What we have argued is that Jellicoe realised what he had to do. He needed to fight only when he was perfectly deployed and the Germans were not – so he wasn’t prepared to let his ships go flying after the Germans.

“What we have argued is that mathematically that was the right decision.”