Don Letts on late 70s punk, Jamaica with John Lydon and facing his demons ahead of Sheffield Showroom screening of Rebel Dread

Punk filmmaker Don Letts isn’t really one for introspection. He likes to get stuck in, start a new project as soon as the last one wraps and always keep moving.

However, he just so happens to be the subject of Rebel Dread, a documentary chronicling his journey through life from formative years in Brixton to his involvement with some of the world’s biggest musicians and becoming a celebrated director.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDirector William E Badgley’s film will come to more than 100 cinemas in the UK in March – including a special screening and Q&A with Letts in Sheffield on Sunday.

In essence, the documentarian has become the documented. How does that feel? “It’s a horrible kind of therapy,” says Letts from London during a conversation over Zoom.

“I had a book out last year called There and Black Again and this film’s out and somebody said to me, ‘You’ve done so much. You’re always working’. I thought, well, what is all that about?

I’ve come to the conclusion: it’s a way of avoiding dealing with myself.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“But now I’m in that position where I’m having to answer questions and promote the film. It’s odd because also I’m not sure I even recognise that guy. In the promo I saw ‘legendary countercultural rebel’ – I don’t feel like that when I’m on the bus.”

It’s true that at 66, Letts is somewhat transformed from the subversive filmmaker who documented British punk’s early heroes on a Super 8 camera, created music videos for the likes The Clash and later performed alongside the band’s guitarist Mick Jones in Big Audio Dynamite, to now being a grandfather who DJs for the national broadcaster and who, in September 2020, appeared on Gardeners’ World tending to his verdant garden alongside wife Grace.

There is no doubting his impact on culture, though, and music has always been central to his life.

“Beyond a job or a hobby, it moves my soul, moves my spirit and keeps me engaged with my fellow human beings and the planet,” says Letts, who presents on the BBC 6 Music radio station.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

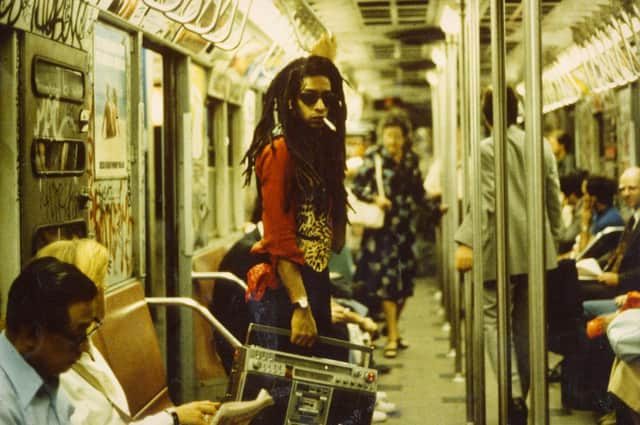

Hide AdBorn of Jamaican heritage, Letts grew up in Brixton, London, under the threat of police harassment and violence in the late 60s and 70s but found meaning through sound and vision. He befriended the likes of Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood, pulled pioneering punks to his Acme Attractions clothes shop, and introduced them to his beloved dub reggae at The Roxy club, creating an explosion of cultural cross-pollination.

Speaking about that time, he says: “It was weird because there weren’t many other black people involved with that. But I was turned on by the energy. The whole DIY thing, the do it yourself, which I think is punk rock’s greatest gift because it was with that energy and that spirit that I picked up a Super 8 camera and reinvented myself as Don Letts the filmmaker.”

His early footage captures artists such as The Sex Pistols performing, the likes of Shane MacGowan dancing and drumming in a Union flag blazer before he fronted The Pogues, and generally brings to life an age when subcultures still shocked.

Letts’ work includes music videos for songs such as Bob Marley & The Wailers’ Exodus, The Clash’s London Calling and Public Image Ltd’s Public Image, but also many documentaries such as The Punk Rock Movie in 1978.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHowever the punk spirit, for Letts, is not something to look back on – it’s a vital force for the present.

“This weird thing that everyone looks back on in the late 70s, isn’t an anomaly, it’s a thing that has a legacy and a heritage and tradition that actually continues. So it’s not a dead thing; it’s a living thing that can take you forward. And I made a film about it called Punk: Attitude, actually, because I was tired of this mohawks and safety pin interpretation. I keep saying to young people: ‘You ain’t missed anything. You’ve just got to find your own version of it and move forward’.”

What does he consider to be examples of the punk spirit now?

“I’m more of a sofa fighting man than a street fighting man these days, but the social, economic, political climate has forced the young to get off their a***s beyond just a click. And I think maybe Black Lives Matter was an example of that. It galvanised people – black and white, it has to be said – for a common cause that was facilitated by technology.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSocial media is a mixed blessing when it comes to rebellion, though.

“If you look at what most people are putting up on Facebook and Instagram, it’s their ugly kids and what they’ve eaten he says, wondering how younger people today might rebel against his own generation, who already have the hair, tattoos, clothes and music that signified a challenge the establishment and elders of his upbringing.

“We’ve done all that. But this technology thing’s interesting because that seems to be the only way that they can rebel against my generation. I’m 66, as old as rock and roll. But the other side of that dynamic is that as much as it could liberate them, and lead the revolution, it has as many of them tied, wallowing in the mud. Because if you look at what’s trafficking at any given time, a lot of it’s rubbish, it’s about ego and make-up and not really ideas.”

Letts was with John Lydon when, following the break-up of the Sex Pistols, he travelled to Jamaica in search of artists for Virgin boss Richard Branson’s short-lived Front Line reggae label.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhile there, Letts tracked down his grandparents, whom he had never met. After knocking on the door, they looked at him in a way that he found disturbing, so he made an excuse to leave and never returned.

It’s a section of the film that cuts to the heart of him having to face the real Don Letts. “That’s a perfect example of something that was too real,” he says.

“You’ve got to understand these people had grown up under colonisation. In some weird way almost missed it. So the Jamaica that me and John were experiencing was something that was actually alien to them.

They were so old school and I was actually more hip to the Jamaica of that present day than they were and I couldn’t deal with it. And I didn’t go back. Basically, I was a coward and left. I just couldn’t deal because to try and explain who I was...I don’t think they could understand how Jamaica had evolved after independence.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdReflecting on whether he regrets not going back, he admits he never had the inclination: “I’d much rather go and throw myself into some project that was removed from anything emotional or psychological than face my own personal realities.”

In that case, what’s next for the man who never stops? For one, he says, “DJing out and about, up and down the UK, nicing up the place with some heavyweight bass – as per.”

The Rebel Dread special screening and Q&A takes place at the Showroom Cinema in Sheffield on Sunday and will be on streaming platforms Bohemia Euphoria and Curzon Home Cinema from Friday.