War and peace

“Because we are a research centre our exhibitions are commas not full stops – they are the beginning of a conversation,” says Lisa Le Feuvre, head of sculpture studies at the Henry Moore Institute, when we meet at the gallery in Leeds to discuss the latest show The Body Extended: Sculpture and Prosthetics.

Exploring the relationship between sculpture and prosthetics, from the First World War up to the present day, the show is the perfect example of art as a provocation, the start of a dialogue. Presenting over seventy artworks, objects and images, it looks at how sculpture and medical science have over the past century extended, augmented and supplemented the human figure. And it’s an interesting angle from which to approach the Great War.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We wanted to look at the First World War but not commemorate it or be nostalgic about it,” says Le Feuvre who curated the show. “We wanted to focus on how this terrible event in our recent history impacted both on culture and on how we understand our bodies. It really is the ground from which so much sculpture has grown.”

The 1914-18 war was the first major global conflict of the industrialised age and the bodily damage inflicted was immense. In the UK over 41,000 veterans lost a limb and in Germany after the war it was estimated that one in every 16 citizens encountered on the street would have sustained a major injury. Sculptors and artists were very much involved in the development of prosthetic limbs and ways of dealing with the catastrophic facial injuries that many soldiers suffered, working directly with surgeons to create masks for those injured in the trenches. “Prosthetic technology develops in times of conflict but it is really about being human,” says Le Feuvre. “We are all full of frailties and we all fail, yet we persist – and that very human condition is at the core of thinking about sculpture.”

The institute has been working with 14-18 NOW, the UK’s arts programme for the First World War centenary, and together they have co-commissioned a new work by sculptor Rebecca Warren, Man and the Dark which stands outside the entrance to the gallery. “Her work goes to the heart of what we are thinking about with this exhibition,” says Le Feuvre. “And it shouts loudly that sculpture is about being human.”

A striking large-scale bronze depicting a pair of powerful, muscular women’s legs striding purposefully, it is mounted on a trolley with casters, referencing the kind of makeshift vehicles used by amputee veterans of the Great War. It also has, says Le Feuvre, a quirky local significance. “At around seven o’ clock every evening, skateboarders come to use the space in front of the building so the sculpture speaks to them too. Rebecca spent a lot of time observing the city. It really is a sculpture for Leeds.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

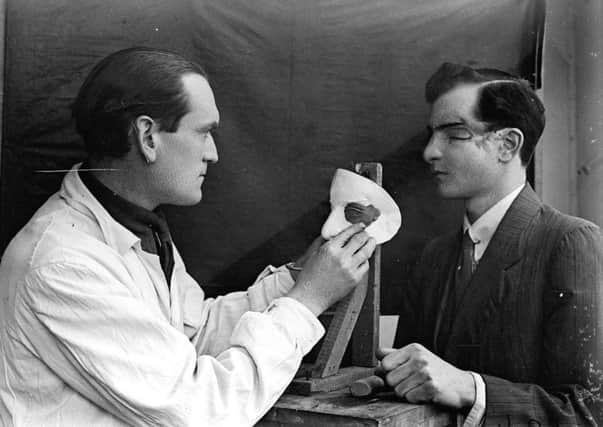

Hide AdAcross the three galleries inside, the exhibition traces both the historical development of prosthetic technology in the aftermath of the First World War as well as the effect that conflict’s distortion of the human body had on the art and sculpture that followed. There are very moving photographs of Francis Derwent Wood putting the finishing touches to a patient’s mask at the Third General Hospital in Wandsworth where in 1916 he founded the Masks for Facial Disfigurement Department, vowing to use “the skill I possess as a sculptor to make a man’s face as near as possible to what it looked like before he was wounded.”

There are two pieces by Louise Bourgeois – a beautifully crafted prosthetic leg, hanging delicately from the ceiling and a gouache painting of it in pink, both entitled Henriette.

“We really wanted to represent Bourgeois in the show,” says Le Feuvre. “Her sister Henriette walked with a cane and Bourgeois, who was born in 1911, had a very vivid memory of working as a guide at the Louvre as a young woman and all the other guides employed with her were older men, injured veterans of the First World War.”

Photographs of German artist Rebecca Horn’s body modification sculptures also feature. Unicorn 1970 sees the artist posing with an elegant horn attached to her head, elongating her body, and Finger Gloves 1972 shows her adorned with macabre-looking extended fingernails, while Yael Bartana’s affecting animation Degenerative Art Lives 2010 reworks Otto Dix’s 1920 painting War Cripples, showing amputee war veterans as automata engaged in an endless, laborious and futile march. There are examples of prosthetic limbs provided by the Imperial War Museum and The Thackray Medical Museum in Leeds, as well as Sigmund Freud’s oral prostheses, after he succumbed to mouth cancer in 1923, on loan from the Freud Museum in London. “We could have filled thirty galleries,” says Le Feuvre. “We boiled down a lot of questions. We were most interested in the analogue body and the processes of making sculpture – casting, moulding, refining and how that relates to the fundamental human desire to exceed and enhance our bodies.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe artworks, objects and images are thoughtfully displayed, making explicit the link between art and science and the way in which imagination and creativity are fundamental to both disciplines. “I am so proud of this exhibition,” says Le Feuvre. “We want people to come and tell us their stories, experiences and associations with the subject. We have spent three years working on this and we are really looking forward to sharing it with people.”

At the Henry Moore Institute to October 23. Free admission.