Why does Flying Scotsman attract so much adoration?

But perhaps only one film has a train as its absolute star... the helpfully titled The Flying Scotsman, a 1929 romantic thriller – half silent film, half talkie, wholly ludicrous. Clips from the film (which we’ll come back to) will feature in the National Railway Museum’s Starring Scotsman exhibition, which opens next Thursday, the day the celebrated loco returns to York after its 10-year, £4.2m restoration.

The exhibition will explore the reasons for the loco’s fame as part of the museum’s five- month Scotsman Season, a jamboree of train-related events: special photography sessions, dinners, themed evenings, and two further exhibitions looking at the loco’s past – it was the first to clock up 100 mph – and its enduring appeal.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt had – still has – terrific allure, both as a railway athlete and a railway aesthete. And it has become (a word used far too freely, but it fits here) iconic.

As Bob Gwynne, associate curator at the museum, says: “If you say ‘Name me a steam loco’ to someone, the chances are they’ll say: ‘Flying Scotsman’. It goes beyond glamour – it’s stardom.

“It’s got mystique, because if you knew anything about its story, you’d know it had a colourful life. There’s something about this old stager. It starts off as a starlet, the star of the show, and then it becomes a jobbing actress in rep, and we’re now into the Dame stage.”

Gwynne and I meet in the NRM’s Station Hall. Down the corridor the museum shop is piled high with Scotsman mugs, caps, T-shirts, postcards, cushions, pens, pendants, key rings, pin badges, fridge magnets, teddy bears, socks (rather fetching), tea towels and beer glasses. There’s Flying Scotsman pale ale, “edible coal” (Pontefract cakes), postcards, scarves, books (one of them by Gwynne himself) and reproduction posters.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

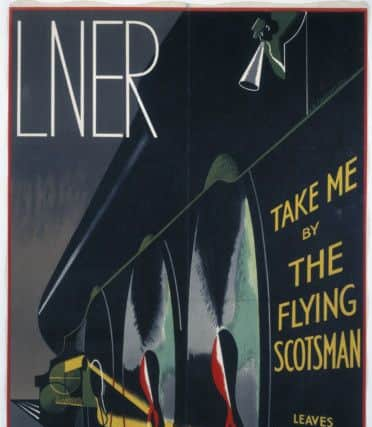

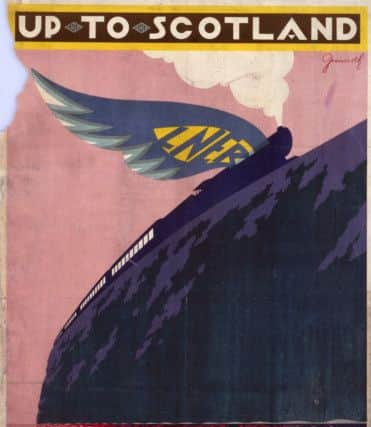

Hide AdPosters for the Flying Scotsman – originally the name of the London-Edinburgh service, and only later of the loco pulling it – are fascinating. They were cunningly targeted by LNER, the company who owned it. The aim was to encapsulate the twin aspects of the Scotsman’s appeal: speed and style. Today you might add its accumulated glamour and sheer survival power.

“It was quite a run from the Scotsman’s humble beginnings as just another locomotive to its glamorous celebrity career; it became the figurehead of LNER,” says Jamie Taylor, the museum’s Interpretation Developer. In the Sixties, he adds, it became a star of the preservation movement, and will now be the oldest steam loco out on the network.

“It only had the 100 mph record for a few months, before it was overtaken by a loco called Papyrus,” says Taylor. “But we don’t remember Papyrus.”

Understandably, perhaps. As a name, Papyrus lacks something in charisma, just as the name German engineers adopted for a powerful new loco around the same time doesn’t quite capture the imagination. It was called The Flying Hamburger.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

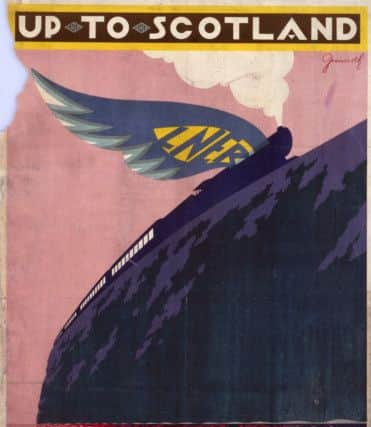

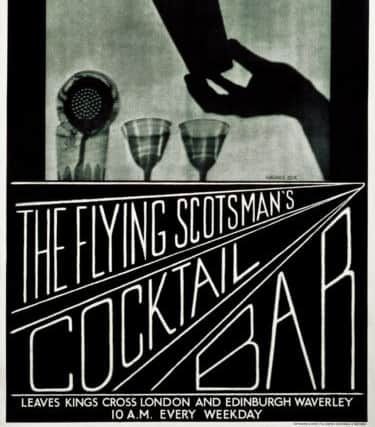

Hide AdThirties posters set out to capture the Scotsman’s power, surging along a cliff top, smoke streaming behind it, with a gigantic bird’s (or angel’s) wing sprouting from its side. Or the sophistication of its cocktail bar, with silhouetted hands gripping a cocktail shaker.

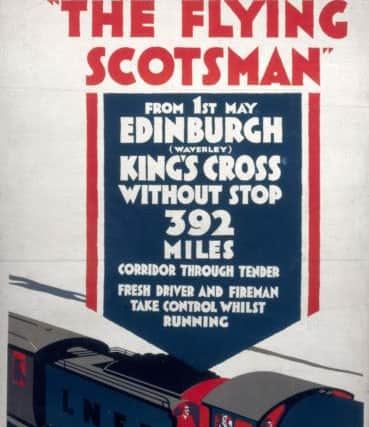

Other posters went for factual stuff, urgently pointing out that the train did the London-Edinburgh run “without stop... 392 miles... corridor through tender... fresh driver and fireman take control while running”.

This was the sort of hard-core, tough-as-rivets detail being bandied about last month when the newly-restored Scotsman pulled its first paying passengers on the East Lancashire Railway. These were trial runs, backwards and forwards between Bury and Rawtenstall, and the speed was cautious.

The carriages were packed with men with rucksacks for whom a mere glancing reference to “vacuum exhaust ejector pipes” could spark a whole evening’s debate.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThese enthusiasts were to be expected; so were the family parties, including children who had never seen a steam loco and were sometimes alarmed by the sheer size of this brooding big beast as it stood spurting steam at the platform.

Less predictable were the crowds lining the route, standing in fields, waving as though the Queen was passing. The media interest was astonishing; the sense of reverence overwhelming; the Scotsman is cherished. There was a tense moment, for instance, as it waited to set off and a TV reporter climbed onto its front to do a piece to camera. One or two of the watching passengers shook their heads. It was a minor outrage; as though he had started juggling with Ming vases.

Scotsmania had overtaken Britain on, as Bob Gwynne puts it, “this cold, wet day in January with a wind with a bit of kick”. How to explain it?

“The Scotsman is like a memory machine, over and above any other steam loco you can name,” he says. “Ask people for a Scotsman story and they might tell you how they saw it when they were six, or when they were 12 and went out with a spotting group, or when Granny went up to Edinburgh on it.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWith this in mind, the museum is setting up a My Scotsman online site where people can post their own memories.

Gwynne, an eloquent commentator on the its cultural significance, talks about its “Thirties resonance, the folk memory of the days when women could have their hair permed in its salon, the days of steam. It has gone beyond being a simple machine; it’s become a symbol of an age. ”

The Scotsman’s allure was the result of clever marketing – about so effectively creating a ‘brand’ (“not a word you’d use in the Thirties,” says Gwynne) that towns and resorts which it never visited included it on their postcards. The image rubbed off, lending glamour even to Herne Bay.

“At the moment,” says Gwynne, “there’s a lot of uncertainty in the world, so you can understand why people are inspired by something that suggests a more stable time.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was the time depicted in the eponymous 1929 film The Flying Scotsman, whose bizarre plot involves the heroine clambering along the side of the train from her carriage to the loco to uncouple it and prevent disaster after the driver is knocked unconscious. Amazingly, the actress (Pauline Johnson) did her own stunt work, wearing high heels and hanging on as the train hurtled along.

LNER had lent its prize loco to the filmmakers in good faith, but were unhappy when it seemed to show the carriages could be manually uncoupled. The film went out with a disclaimer.

• Starring Scotsman: National Railway Museum, Leeman Road, York (0844 815 3139, nrm.org.uk) from February 25 to June 19. Open daily, free. Full details of the Scotsman Season on www.nrm.org.uk/flyingscotsman