A middle-class jamboree, or is culture worth every penny? – David Behrens

That’s certainly how the Arts Council sees it, having based its manifesto for reopening the sector on what it grandly calls its “seven principles” of social inclusion.

But what about the stubbornly un-woke stigma of class discrimination? There remains the nagging feeling that the arts are elitist, and perhaps becoming more so. This week, a Leeds councillor dared to say so out loud.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was all very well, ventured Labour’s James McKenna, to spend £32m on a creative festival in the city the year after next, but wasn’t it all just a middle-class jamboree? Constituents of his in Armley whose universal credit had just shrunk by £20 a week were going to need more than culture to see them through.

On one level, he’s right: high-concept events such as Leeds 2023 can seem like the preserve of the bourgeois. But culture is also an escape route, and there is at least one former resident of Armley who can attest to its life-changing potential.

Alan Bennett grew up feeling that life was something that happened elsewhere. His childhood, he recalled, was “dull, without colour, my memories done up like the groceries of the time in plain, utility packets”. It was the arts – specifically the paintings and sculptures housed within Leeds Art Gallery – that opened his eyes to the world outside, and gave him a way out.

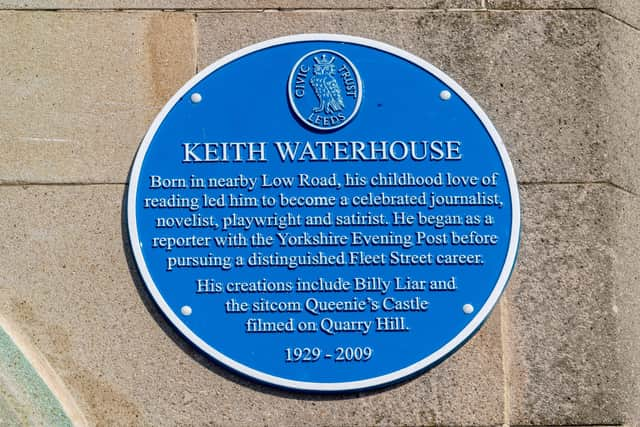

Another writer, Keith Waterhouse, hailed from a back-to-back in Hunslet on the other side of the city centre, and told a similar story. Culture, in whatever form he could find it, was what fired his imagination.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThat in itself makes the money being spent on Leeds 2023 a sound investment. No matter that the project is rooted in rancour, following the UK’s removal from the European Capital of Culture programme. Leeds had hoped to win the crown but instead struck out on its own, and there are other Bennetts and Waterhouses out there who will thank them one day.

Besides, there are recent examples of the positive legacy of similar events not far away. The immediate aftermath of Hull’s year as UK City of Culture in 2017 saw more people attending creative events than ever before, and 11 per cent more visitors coming to the city. And in Liverpool, the previous European Cultural Capital, unprecedented investment was made possible along the waterfront and in the city centre, which now stand as benchmarks for the economic case for culture.

Bradford, a city more diverse than most, is next in the queue, having set out its stall to become Britain’s City of Culture in 2025. It’s currently on the judges’ long list, along with other centres including Cornwall and County Durham, which are not even cities.

The official line from the organisers is that the title would “transform Bradford into a creative powerhouse”, but the promise of jam tomorrow has become rather familiar there over the last couple of generations. Indeed, the city’s recent story is one of waiting for change rather than instigating it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFrom the long-delayed and in the end underwhelming Broadway shopping mall to the much-debated rebirth of the old Odeon cinema, Bradford has been on the back foot compared to its bigger neighbour nine miles to the east. While Leeds was seizing the initiative with a cultural festival of its own, Bradford was putting its fate in the hands of the Culture Department in Whitehall.

Nor is there much evidence that the public supports Bradford’s bid. One local poll – admittedly not a very scientific one – showed that 55 per cent were actively against it.

Even this week, the city council was presenting itself as beholden rather than emboldened, with members bemoaning delays to £15m of unspecified “community renewal” projects which could “kickstart the local economy”. This does not smack of a city thriving on its initiative.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd that’s why it’s hard to criticise the cultural ambition of Leeds 2023 – not in spite of the poverty identified by Mr McKenna in Armley, but because of it. Aspiration, whether by individuals or institutions, is the real Northern Powerhouse and those who harness it are its most important drivers. And there’s nothing at all elitist about that.

Support The Yorkshire Post and become a subscriber today. Your subscription will help us to continue to bring quality news to the people of Yorkshire. In return, you’ll see fewer ads on site, get free access to our app and receive exclusive members-only offers. Click here to subscribe.

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.