Archbishop of York: Future of our local churches after pandemic

IT WAS during a quiet moment of reflection in York Minster when the new Archbishop of York appreciated how Covid was irrevocably changing the Church of England.

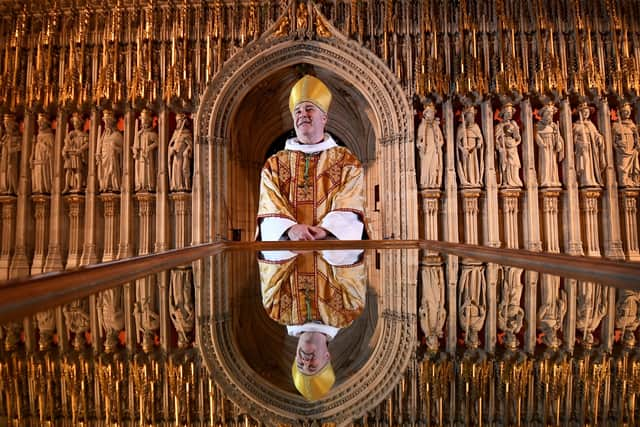

The Most Reverend Stephen Cottrell remembers it well. He’d just presided over one of his first Christmas services since succeeding Dr John Sentamu, that indefatigable ‘man of the people’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdYet all he could see was row after row of empty pews in this hallowed ‘House of God’. And an eerie silence at a time of supposed joy. It was a not the first Christmas in York that he envisaged when named as the 98th Archbishop just weeks before a global pandemic struck and prompted soul-searching.

He shared his personal pain with the Minster’s Dean, organist and two others involved in the online service’s broadcast. “There’s a tiny group of us and my response was ‘There we are, we’re in the Minster and there’s nobody there’,” the Archbishop told The Yorkshire Post. “I’m kind of feeling a sadness and the head verger says to me ‘I understand that but 9,000 people were watching that service’.

“I say ‘okay, that’s interesting, four or five times the number of people we can get into the building’. What does it say in terms of national life? That doesn’t say ‘oh we’ve become this nation of atheists’. I don’t want to put a label around people’s necks, but I think I would say ‘we are a nation of people who want to live well, want to live by a set of shared values, want to live with mutual respect.

“Those British values run deep and, of course, they have their roots in the Christian tradition so at a time of crisis, as we have lived through, people are turning to the church and, for them, lockdown has meant turning online in greater numbers than we anticipated.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“All that says to me is we, in the church, shouldn’t be so hard on ourselves and we should find hope, take heart and reach out to say that the Christian faith can make a difference.”

Those words are significant because the sub-title to the Archbishop’s new book Dear England is ‘Finding Hope, Taking Heart and Changing The World’.

It was prompted by a chance conversation with a stranger while buying a coffee – flat white for the record – as he waited to catch a train.

As the barista finished the order, and the clergyman looked anxiously at his watch, this young woman surveyed his cleric’s collar and asked “What made you become a priest?” As he often alludes, the obvious questions can also be the most complex.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe short response was God – and his Christian faith. The more substantive answer was a deep desire “to change the world”. “I also told her that I had made a diagnosis,” he recalled. “I told her I thought the problem lay in the human heart. I told her that I thought the human race needed a heart transplant. And I told her that, as I saw it, only God could do that.”

The consequence is a cathartic book and timely study into how the Church can reach out to lapsed followers, the agnostic or, in the case of his travelling companion, the indifferent in the wake of one of the pandemic’s many great paradoxes.

For, while the CoE is just one of the many traditional institutions coming to terms with contemporary challenges, Covid has – in many areas, but certainly not all – seen a reawakening of the local church in their communities.

And, as the Archbishop himself says, never have so many international Christian conferences been blessed by his presence via Zoom. “I’ve spoken all over the world in the past year,” he says. “Spain, Canada, Australia, France.” Yet he then speaks of his frustration at being largely confined to Bishopthorpe Palace – or York Minster. “I long to get out and about and to meet people,” he stresses. “I have found that frustrating but that’s where we all are.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut this interlude has given the Archbishop time to ponder – as distinct from his predecessor’s penchant for perambulations. “The importance of the local, I think that’s the real lesson we have learned,” he reflects. “What is the Church of England? It’s a network of local churches and where we are serving that locality well, that is reaping a benefit for the community.”

He then addresses digital services – or, as he refers to, “the online thing”. “We are only just beginning to learn what the significance of that might be,” he acknowledges. “The fact that an organisation like the church, with our history and traditions, was able to transition to go online so quickly and effectively, I would call that a nice a problem to have. It’s the first time for ages we’ve got a real growth problem rather than a decline problem.

“The future beyond Covid will be...the jargon is a ‘hybrid future’. We long to return to our churches and do all those things, but the online community will continue.”

The Archbishop does, however, believe it is important that the Church speaks out on key social issues, like housing, while being critical, if necessary, of policies rather than politicians. “Speaking from Bishopthorpe Palace, if I see some people drowning in the river Ouse, I will do what I can to pull them out,” he explains.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“If I keep finding people drowning there and I keep pulling them out, sooner or later I’m going to ask the question ‘Whose upstream pushing these people in? Why is this happening?’ Loving your neighbour isn’t just about caring for the needs of your neighbour, it’s about asking the hard questions ‘Why is your neighbour in need? Why has this happened?’

“The Church is very good at caring for the homeless but sometimes, in a wealthy civilised country like ours, you have to ask ‘Why are all these people homeless?’ I don’t believe for a moment any politician woke up one day to say we will have a policy to make people homeless but, sadly, the effects of some policies have led to that and we need to point that out and perhaps we need a bigger vision.”

But how will Archbishop Cottrell ultimately judge the success of his own mission from a pastoral and personal perspective? “I’m not sure is the honest answer,” he concedes. “Let me tell you what I long for. I do long for our churches to grow. I do long for that. I think our world will be a better place, I think people would lead happier more fulfilled lives in communion with God. Even if that doesn’t happen, I won’t think I have failed because I don’t think I am personally responsible for that – I have my part to play.

“I also long for us to live in a fairer, better world where families and households and communities are properly supported, and I think the Church has a part to play in that, and I certainly want to do all that I can to develop and strengthen the life of the local church.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We might even increase and develop that presence into new communities, that we will have worked out what it means to be an online church as well as a physical church. They are the things that I hope for. If that bears fruit with more people being part of the Church, then I will rejoice.” He means it.

ARCHBISHOP Stephen Cottrell hopes his ‘Dear England’ book can lead to a debate about how Church, and communities, can be reinvigorated.

Conscious that English identity can attract “negative” behaviour, or reactions, he says: “I don’t think England is a nation of atheists. We are not a nation of believers and church-goers either.

“I believe in the fundamental goodness that people want to live a better life and the Christian faith, which has shaped our narrative in the past, can shape it again in the future.”

To launch the book, he will be in conversation with Adrian Chiles on Wednesday at 7pm – for details go to https://www.archbishopofyorkyouthtrust.co.uk/support-us.

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.