‘I’ll always think of him as ‘Dr Death’’ - Meet the Yorkshire bereavement expert helping hundreds through Covid grief

“As a nation, we don’t handle death very well,” reflects Dr John Wilson. “It is the last taboo. Sex was the Victorian taboo, our 21st century one is death and dying.”

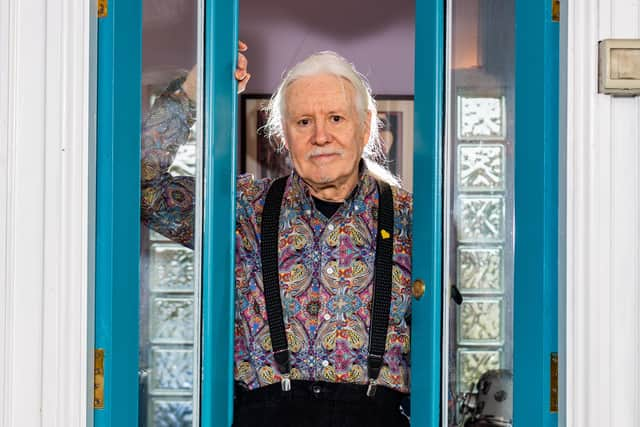

Dr Wilson, who this year has set up an online support group for people bereaved during the Covid crisis, speaks from considerable personal experience. The director of bereavement services at York St University’s Counselling and Mental Health Centre has helped hundreds upon hundreds of people cope with the deaths of loved ones down the years, while also suffering his own terrible loss.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDr Wilson was working as a primary school teacher in Barnsley and living in Doncaster in 1982 when his 14-month-old son Paul died of cot death.

“I got a call from Doncaster Royal Infirmary to say he had been taken ill and could I drive over there,” he explains over the phone from his home in Kirkbymoorside. “I didn’t know it at the time but he had already died at that point. He’d had a very sniffly cold the previous day and he died in my wife’s arms around about lunchtime, it was very, very sudden.”

Dr Wilson says he didn’t fully process the tragedy until he was retraining as a counsellor more than a decade later. “I didn’t deal with it very well. I tried to carry on as normal – it didn’t catch up with me until 1995 when I did an assignment on the counselling course on cot deaths. I had been hiding away.”

Wilson had been working as a senior lecturer in education at Leeds Metropolitan University (now Leeds Beckett) when he decided on a career change. “I took early retirement in 1997 at the age of 50 and retrained as a counsellor while I was in my last two years of work. There had been a student who was having some real personal difficulties and I was trying to support her as her tutor but I felt I was out of my depth. I did a short six-afternoon counselling skills course and I realised this was the career for me.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 2000, after getting a Higher Education Diploma in therapeutic counselling, Dr Wilson got a job at as a bereavement counsellor at St Catherine’s Hospice in Scarborough. As well as working with hospice patients and their families, the job involved community work comforting loved ones of people who had been murdered, passed away in car accidents and died by suicide.

He says it was a steep learning curve. “When I joined I was aware the previous occupant hadn’t stayed very long in the job. I had been a volunteer for 12 months seeing two to three people a week before I got the job. When I started doing it 9-5, five days a week, I did begin to think I wasn’t able to do this. It was saying that out loud to my line manager that helped break the spell. It did get easier but it is always challenging.”

Wilson says the insight of bereavement counselling pioneer Colin Murray Parkes, who set up the nation’s first hospice-based bereavement service, was a major help in not becoming overwhelmed by helping others process intense grief.

“Colin Murray Parkes said some incredibly important words on this that have become my go-to mantra. He said that when somebody is in the room with you, there are the centre of your world. But when they leave the counselling room, they go back to their world and you go back to yours. It is really important.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSo what represents success when it comes to bereavement counselling? “We are not there to take away the pain and make them feel better,” Dr Wilson explains. “We are there to share that pain with them. Grief is a healthy process and in time the intensity does fade. Where counselling makes a difference is you are helping people to make sense of what happened and finding new meaning in their life and their feelings. It is that sense-making that really makes a difference and gives people some control back.

“Sometimes you get very emotional. At the hospice there was one patient where I would always be in tears at the end of her session because of her bravery and I always needed a hug from a colleague afterwards.”

He completed a doctorate in counselling in 2017 after six years of juggling his work commitments while doing his PhD. He says it led to his wife Sandra, who he married in 2000 with the pair both having grown-up children from previous marriages, affectionately giving him the nickname of ‘Dr Death’ because of his passion for exploring the subject of bereavement.

“I was self-motivated and self-funded, working a lot of extra hours to help pay for it over six years. I wrote something every day of the week for six years - I ended up with 150,000 words and took out about one-third of them for the final dissertation. My wife was tremendously supportive.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLike so many people this year, Dr Wilson’s working life has been upended by coronavirus and in mid-March he began working from home – partly as a result of being in risk categories due to his age and his asthma.

In early April, he established a mutual support group on Facebook for both those bereaved directly by Covid-19 and others who had lost loved ones during the pandemic but were unable to grieve in the normal way, with funerals restricted and families prevented from seeing each other.

“It goes back to the idea of making sense of things – you make sense by being there towards the end of life. In these kind of circumstances, you can’t make sense of it because you didn’t see the progress of their illness or you weren’t able to say goodbye. When the virus wasn’t properly understood, the precautionary measures were very strict – people were sealed in coffins and there was no chapel of rest viewings. That had a huge impact. There is a huge amount of trauma and also a huge amount of anger.”

Dr Wilson set up the group after realising ordinary bereavement services were either closed because of lockdown or under immense pressure. The group now has 380 members who share help and advice with each other, while Dr Wilson and his colleagues at the university have provided free counselling for the most vulnerable and isolated individuals.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe university recently posted an article containing some of the experiences of people who had been helped through being part of the group. One, called Hannah, was unable to visit her mother for 10 weeks before she died in a care home and explains that part of her pain has come from the reaction of other people to the cause of her mother’s death.

“One of the awful things about losing someone to Covid is the responses from others,” she says. “When I tell people I lost my dad to cancer I am met with sympathy. When I tell people I lost my mum to Covid, often I am met with questions. Was she old? What else did she have wrong with her? Are you sure it was Covid? Then there is the relentless media coverage. There is no escape from the constant reminders. The news coverage, the complaints about the masks. The claims that it is a hoax. It is impossible to really begin the healing process, you think you are doing well and then you hear or read a comment and it all floods back. It is a million times harder to say goodbye to your mum via an iPad. Losing a loved one is always awful, it’s always a different experience but Covid is unique, unknown and unrelenting.”

Dr Wilson says that experience is sadly common, saying that some of the dismissive comments about Covid go back to national taboos around death. “There are plenty of conspiracy theorists but there are also a lot of people who aren’t into conspiracy theories but find it comforting to believe they are somehow safe.”

The Facebook group is a private one in a key part of Dr Wilson’s efforts to make it a safe space for people to share their feelings.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn addition to his work at the university and in the mutual support group, Wilson has also been finalising his latest book, The Plain Guide to Grief, which is due to be published in the next couple of weeks.

The book, which tackles subjects like divorce and redundancy as well as death, had been finished in April but he has added a further chapter in response to the pandemic.

He says one of the most fulfilling parts of his work is when he has initial conversations with people dealing with grief and is able to reassure them.

“About half of people who meet, you can reassure them they don’t need counselling and are managing perfectly well, that they are grieving really healthily and you can say ‘keep doing what you are doing’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“If somebody can talk fairly normally and may be slightly tearful but not overwhelmed, that is a really good sign. If they can tell stories and reminisce about the person and raise a smile that means they are already cementing happy memories as well.

“If a person is able to sometimes grieve and sometimes get on with other things, that is crucial. But it is not healthy to immerse yourself in work or alcohol.”

For those who have joined the Facebook group, Dr Wilson’s help has been invaluable.

Hannah writes: “John has posted advice, quotes and articles which have helped explain grief, the grieving process, and ways to get through the days. The members in the group are all strangers but we have a shared experience, and we know that we will all offer support. Nobody tries to take the pain away or make you feel bad for it, we all know it is part of grief and that the pain needs to be experienced, discussed, and worked through. I feel less alone thanks to the group. I feel less lost and less of an inconvenience. I am very glad that I found it.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnother member called Joy says: “I joined this group because it is safe and I didn’t want everything in the public domain following my husband’s death on March 26. This group has kept me sane during my most difficult times when life has been so dark, it allows me to share my problems and feelings without being judged and people who understand ‘little steps’ sometimes forward, sometimes back, have stuck with me through this journey. Those two little words keep me going. John always tries to keep us safe and supported with his wise words. He allows us to be ourselves, good or bad. This group may be the only outlet for some people and am lucky to have found it.”

A woman called Mary adds: “It initially gave me somewhere to express my thoughts and feelings without fear of judgment, knowing I would not be dismissed. As the months have passed, I can feel how I have changed, and rather than getting back to ‘the old me’, I have grown to become ‘the new me’. I have found John to be genuine, approachable, knowledgeable and kind. His passion for the subject shines through everything he does. I will always think of him as ‘Dr Death’.”

University to host international conference this weekend

York St John University will host an online event this weekend examining global responses to bereavement during the pandemic.

It will feature speakers from the UK, US and New Zealand and will be chaired by Professor Lynne Gabriel, director of the university’s counselling and mental health centre.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdShe says: “We wanted to offer an accessible, vibrant event that engages with the personal, professional, and political features of grief and loss during a global pandemic. It’s not just for academics, it’s for everyone.”

Delegates can choose a registration fee that is appropriate to their budget, between £20 to £40.

Support The Yorkshire Post and become a subscriber today. Your subscription will help us to continue to bring quality news to the people of Yorkshire. In return, you’ll see fewer ads on site, get free access to our app and receive exclusive members-only offers. Click here to subscribe.

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.