Jock Stirrup: We must learn lessons of peacetime as well as war

The centenary commemorations have been very successful in bringing home to those growing up in the 21st century the nature of the conflict and the impact that it had on a whole generation in this country.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe major battles have been acknowledged and analysed, the impact on the country and its population have been examined closely and the effects of the war on local communities and organisations have been highlighted in all sorts of revealing ways.

I congratulate all those in schools, museums and veterans’ organisations who have worked so hard to bring these things out of the shadows of history and into the light of contemporary thinking.

However, I have a reservation. Some six years ago, during our first discussions about the centenary, I made the point that while we had to mark the key milestones of the war, there was a larger and, in some ways, even more important perspective.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIf the centenary was to be more than a passing acknowledgment of a dreadful period in our history, if it was to be of lasting benefit to coming generations, then it would be crucial to focus not just on the courses of the war, but on its causes and its consequences.

Happily, in the months leading up to August 2014, there was a great deal of debate over the events, misadventures and miscalculations that plunged the world into such a catastrophe. We have now, though, been through over four years of commemorative events. They have been superbly arranged and movingly executed, and even in the most difficult of circumstances, they have struck the appropriate tone. But four years is a long time, and there is a sense that the centenary of the Armistice is a good point at which to bring the process to a close. That would be a serious mistake.

After a great many missteps, years of stalemate on a number of fronts and bloodletting on an unimaginable scale, in November 1918 the allies finally achieved a decisive operational victory. Over the following few years, however, their diplomatic and political failures turned this into a strategic defeat of the first order, a defeat that would set us on the path to the Second World War and to even greater carnage.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe hubris of victory, the increasing alienation of Germany, the creation of the “stab in the back” myth, the failure of the United States to engage properly in the global commons, the San Remo agreements on the division of the remnants of the Ottoman Empire which we see unravelling before our eyes today – all these things, and others, led us eventually to a much darker abyss than the one from which we emerged in November 1918.

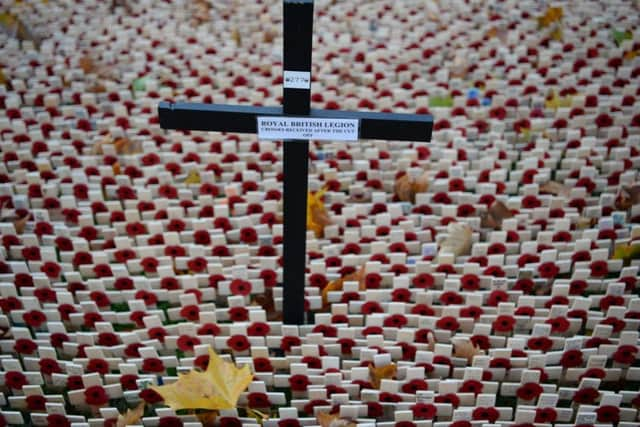

As part of the Armistice centenary events, torches have been lit at the Tower of London. These torches represent the rekindling of hope following the devastation of the war, but after 1918 the flames of hope flickered only fitfully before finally guttering to extinction in the 1930s. They failed in their promise because people forgot that peace is a fragile thing and that it can be sustained only through constant effort. This lesson was learned in 1945, when the victorious allies put in place, and committed to, institutions and processes to nurture the global commons. When the peace of Europe was again threatened, by the division that split former comrades in arms between East and West, the response was one of unified and determined purpose exemplified by Nato.

Today the institutions that have served us so well for more than 70 years are under threat. They are, of course, imperfect and in some cases, no doubt, they are in need of renewal, but they should not therefore be cast aside as so much obsolete bureaucracy.

If the years immediately following the Armistice teach us anything, it is that the rejection of collective security in the pursuit of an illusory idea of self-interest puts us all at risk, and that a failure to unite, with all the messy compromises that this entails, leaves us exposed and vulnerable to the dangers of an uncertain world.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe world of 2018 is not the same as the one of 1918. We cannot draw direct parallels between the two eras. However, as Mark Twain reminded us, while history never repeats itself, it does sometimes rhyme. I have an uncomfortable sense that we are hearing such a rhyme now.

Those who sacrificed so much in the First World War were let down by those who sought to make the peace. If we can use their example to help us to do better, then that sacrifice will not have been wholly in vain. That is why the centenary of the Armistice should not be an end, but a new beginning of reflection, debate and learning.

Lord Stirrup is a former Chief of the Defence Staff. Now a cross-bench peer, he spoke in a House of Lords debate on the Armistice. This is an edited version.