Forgotten pleasures

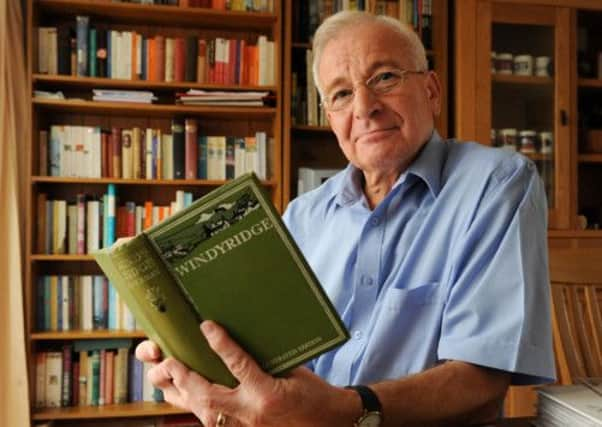

Since the early 1970s, David Copeland had wondered why the house his brother bought in suburban Newcastle was called Windyridge; it wasn’t, after all, on a ridge and it wasn’t particularly windy.

Then, in the late 1980s, he discovered a book called Windyridge in a charity shop. Written by Willie Riley, it was a tale of life in a fictional Yorkshire Dales village. “I started to read it and I couldn’t put it down,” says Copeland, a retired railway manager from York. “So I did some research and discovered that Riley was once viewed on the same level as JB Priestley and Thomas Hardy.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFirst published in 1912 after an unlikely series of events, Windyridge was marketed as “The Great Yorkshire Novel”. It stayed in print until 1961 and sold half a million copies, inspiring devoted fans – as in Newcastle – to name their homes after it. Riley (1866-1961) went on to write 38 more books, which sold over a million copies between them.

And now? Windyridge is back in print, with a fascinating introduction by Copeland, but its centenary last year passed with little comment and Riley, who ran a Bradford lantern-slides business, is now almost entirely forgotten. Which makes a forthcoming Sheffield celebration of him and two other Yorkshire authors (with Copeland as one of the speakers) an intriguing prospect. Called Yorkshire Writers, it also features Winifred Holtby, celebrated author of South Riding, and Phyllis Bentley, whose 1932 novel Inheritance, a saga about a century and a half of the West Riding textile industry, went through 23 editions in 14 years.

The celebration, at Sheffield Hallam University, is part of the city’s Off the Shelf Festival of Words and is likely to spark debate about whether, from the Brontës through to John Braine and Stan Barstow, there’s such a thing as a “Yorkshire novel”. Does the county has a definable fictional voice?

“I’m not sure I believe in the idea of a ‘Yorkshire novel’,” says Professor Chris Hopkins from the university, who will be taking part in the celebration. “But there were certainly a lot of people who wanted to write about Yorkshire and a lot more who wanted to read about it.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

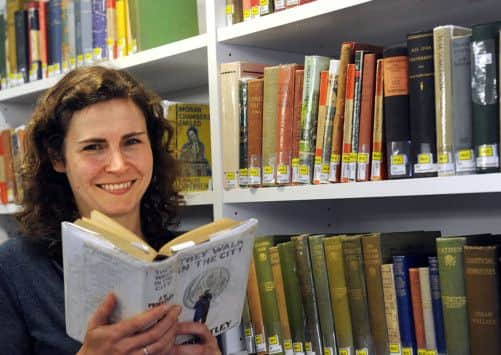

Hide AdDr Erica Brown, research fellow at the university-based readerships and literary cultures 1900-1950 project, pinpoints a Yorkshire characteristic often reflected in the novels the county has inspired. “Yorkshire has the self-confidence to think it’s a fit subject for a novel in itself, and not every region could say that,” she says. “And,” adds Hopkins, “there’s a feeling that it’s something that the rest of the country should read about.”

He will be discussing Phyllis Bentley (1894-1977), the daughter of a Halifax mill-owner who was regarded in her day as the first successful regional novelist since Hardy. Stan Barstow, Horbury-born author of A Kind of Loving, once told a radio interviewer that reading Bentley inspired him to write because she wrote about a world he knew.

“She isn’t very well-remembered now,” says Hopkins. “But she writes well and interestingly and, unlike a lot of Yorkshire novelists, she didn’t move to London; she had to stay in Yorkshire and look after her mother. She once said that expressing passion wasn’t easy – you couldn’t write a love scene in a novel based here, because laconic Yorkshiremen don’t do that kind of thing.”

Bentley, sometimes patronised as “provincial” by the metropolitan (i.e. metro-vincial) critical elite, has a worthy place in the readerships and literary cultures collection of “middlebrow” novels. There are about 1,000 of them, by authors who were once widely read but may now have fallen by the literary wayside: Warwick Deeping, Nevil Shute, Howard Spring, Victor Canning, Gilbert Frankau.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne who rises far above the norm is Winifred Holtby, who died cruelly young – just 37 years old – in 1935. “How I envied her,” Phyllis Bentley wrote. “Tall and fair and handsome ... that lovely speaking voice and that precision of English ... those interesting well-cut clothes, that Oxford degree.”

Holtby’s life and work will be discussed by her biographer, Professor Marion Shaw of Loughborough University. “Without South Riding, she wouldn’t be remembered quite so much,” says Shaw. “It attracted a solid middlebrow readership. I’ve taught it to students who had never heard of it and they take to it as a kind of late realist novel. Holtby wanted to communicate with people, to get through to them. I first read it when I was 14 because my mother liked it very much; I read it as a love story and only later saw its political and social depth.”

Interest in the book, a sweepingly ambitious study of East Yorkshire life and politics, was revived two years ago by a highly condensed BBC adaptation starring Anna Maxwell Martin as its central character, the schoolteacher Sarah Burton. “I was cross with the BBC,” says Shaw. “They only gave it three episodes and it could easily have had four. It was a cheap version and I wrote to the BBC to tell them so.”

And so to Willie Riley and his 39 books, including the unpromisingly titled 1936 novel The Man of Anathoth (“Being the life of the Prophet Jeremiah as conceived by W Riley”). “I find it extraordinary that he’s so completely forgotten,” says Erica Brown. “He was so prolific and he sold so well.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne possible clue to his present obscurity is the dated style of Windyridge, which one recent reader described as “so cosy it’s almost camp”. Certainly its homely, sepia-tinged, soft-focus tale of the adventures of a southern woman settling in a Yorkshire village seems very much of its time; but that was the idea.

Willie Riley, a Methodist lay preacher, never intended to become an author. He started writing the novel, his first, in weekly episodes to amuse two young women friends of his family, basing the Dales village of Windyridge on Hawksworth near Baildon. They persuaded him to try to get it published; he was reluctant, but put the names of four publishers in a hat and pulled out that of a newly launched company, Herbert Jenkins. They quickly accepted the book and were gratified by generally enthusiastic reviews.

This tale of “the simple lives of the Yorkshire peasant folk”, as the Sheffield Daily Telegraph described it, would “reach the hearts of a multitude,” predicted The Standard. Some reviewers compared it to Mrs Gaskell’s Cranford. Others were less keen. The long-forgotten T.P.’s Weekly thought it “set on the safe, quiet way of the sentimental, the blandly narrative, and the all-ends-well style of fiction”. All the same, Hawksworth became a tourist destination; tea shops sprang up to cope with the literary pilgrims.

All this background has been exhaustively researched by David Copeland, who has an evangelical zeal for Riley. He could initially find “not a sausage” about him, but traced the author’s nephew who showed him five boxes of Riley’s notebooks, scrapbooks and albums. He wrote a thesis on him for an MPhil degree, has written an unpublished biography, and has traced the book’s locations.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhat he discovered was a modest man. “He didn’t promote himself at all. He just enjoyed writing and loved the Yorkshire Dales and the people of Bradford.

“The book is about how people behave under pressure and behind it all is an underlying foundation of Christianity. He said he wanted to make God better known in a world where he’s very much misunderstood.”

Unexpectedly, Windyridge prompted a small outbreak of uncharacteristic Yorkshire modesty. “One cannot help a certain shock of astonishment,” said the Bradford Daily Telegraph, “that a Bradfordian should have written a novel at all”.

JB Priestley might have had a few pithy West Riding words to say about that.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdYorkshire Writers 1900-1950 is at Sheffield Hallam University on Friday, October 25, 1.30pm. 0114 225 4003, www.reading19001950.wordpress.com.

Off the Shelf festival runs from October 12 to November 2. 0114 273 4400, www.offtheshelf.org.uk.