How the Brontës brought health to Haworth

Exactly two centuries after the teacher and cleric Patrick Brontë accepted the post of resident curate at Haworth, a new exhibition on his life has unearthed a lost world of home-made medicines and opium, and of life and death in one of the country’s most deprived and unhealthy communities.

The father of Emily, Charlotte and Anne Brontë would spend four decades – the rest of his life – in the parsonage that is now a museum to his family. But neither his wife nor his children lived to see the reforms he wrought on the village.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Haworth at that time was one of the worst places to live in England. It was considered as bad as the poorest districts of London for its sanitation,” said Sarah Laycock, curator of the year-long anniversary exhibition, Patrick Brontë: In Sickness and In Health.

“Life expectancy was only 27 and half the children did not live to see their sixth birthday.”

Rev Brontë’s papers, which form part of the display, betray a family whose health was already fragile as they prepared for life in Haworth – then a bleak enclave of industrial mills.

His wife, Maria, died the year after they moved into the parsonage, and he and his daughters were plagued by eyesight and other problems.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA pair of Charlotte’s spectacles examined by modern opticians reveal her sight to have been “terrible”, Ms Laycock said, adding that Patrick had been forced to undergo an operation without anaesthetic to remove cataracts.

Charlotte accompanied him to the clinic in Manchester for the procedure and is said to have begun writing Jane Eyre while he recuperated.

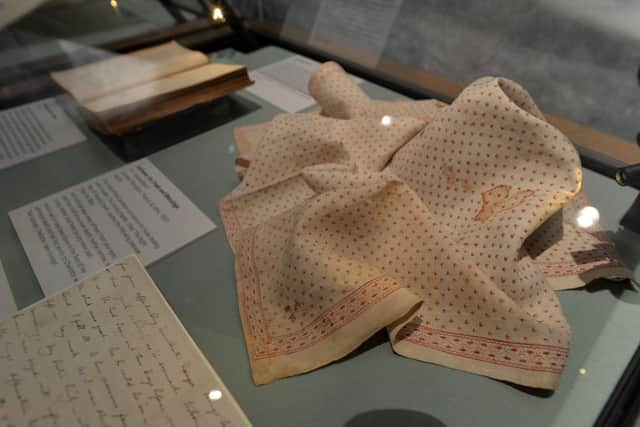

The exhibition also includes a blood-spattered handkerchief that had belonged to Anne Brontë after she contracted tuberculosis, a disease that had similarly afflicted her brother, Branwell.

“The family shared beds and were quite close physically with each other, which meant the diseases spread,” said Ms Laycock.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPatrick’s papers contain a recipe for home-made headache pills similar to those found in Charlotte’s medicine box. But his handling of Branwell’s addiction to alcohol and laudanum, an extract of opium, is less well recorded. A bottle of the potion has survived.

The health issues of the Brontës themselves were replicated many times over by those of Patrick’s parishioners.

“Because he was a minster, he had to have some knowledge of how to cure people of common ailments, because they didn’t have the money to see a doctor.

“He put all his efforts and energies into trying to make things better for the people of Haworth,” Ms Laycock said.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“He was forward thinking in looking at prevention, not just cure. When they realised the cause of the high death rate, he established the Haworth Board of Health and they held meetings on how to stop the spread of cholera.

“Unfortunately, his own family didn’t live long enough to see the benefits.”

Asked if conditions in the village might have contributed to the early deaths of Patrick’s daughters, Ms Laycock said: “It was pretty grim anyway, living in England at that time.”